[This blog post is an excerpt from a commentary published at TSI last week]

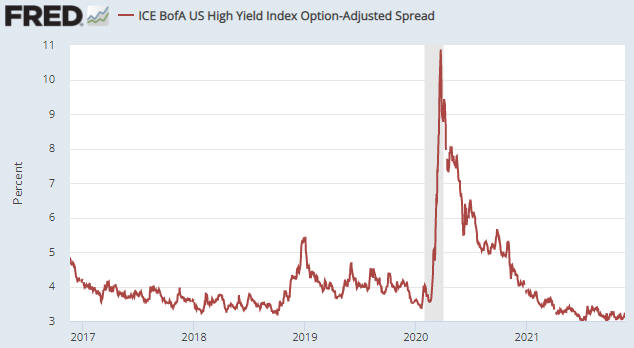

After the FOMC meeting on Wednesday 26th January, the Fed — via a post-meeting statement and a press conference — made it clear that it plans to end its bond monetisation (QE) program in early-March and hinted strongly that it will make its first rate hike of the cycle in mid-March (the time of the next FOMC meeting). The Fed also discussed its intention to significantly reduce its balance sheet.

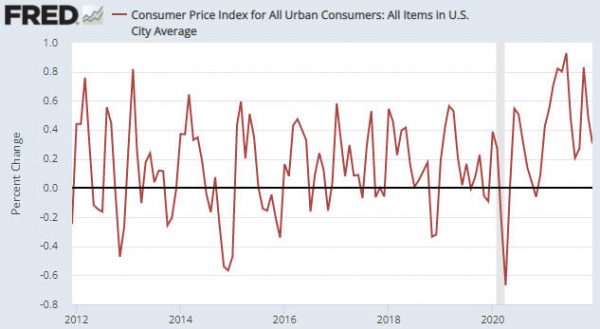

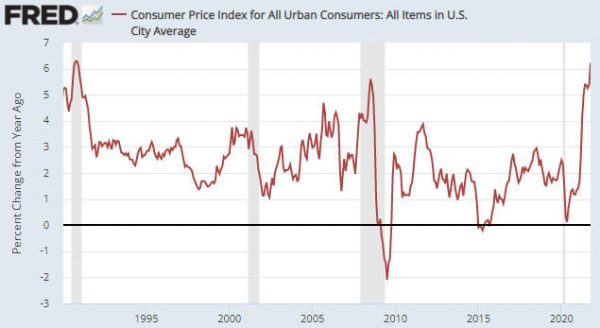

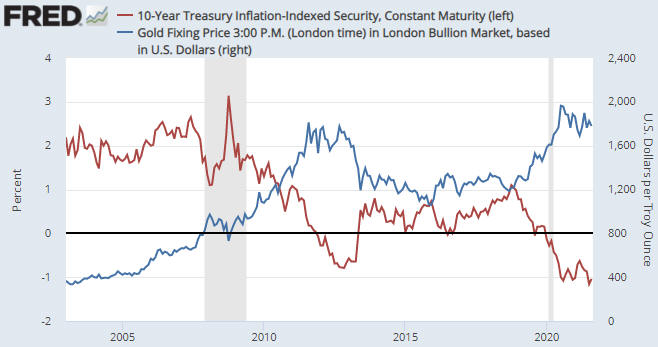

What the Fed expects to do and what it ends up doing are often very different. Currently the Fed expects to hike its official interest rate targets in March-2022 as part of a rate-hiking campaign that will entail four rate hikes this year and more rate hikes next year. However, we suspect that the March-2022 hike will turn out to be this year’s only hike, because by May-June it will be clear to the backward-looking Fed that both “inflation” pressure and US economic growth peaked in 2021.

Moreover, we are confident that the Fed will never significantly reduce its balance sheet. It may well start to reduce its balance sheet over the remainder of this year by not replacing maturing debt securities, but it will react to the next serious economic decline the way it has reacted in the past. As a result, its balance sheet probably will be much larger in 18 months’ time than it is today.

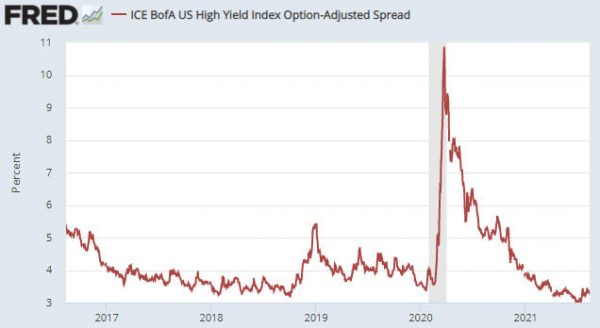

The insurmountable problem faced by the Fed is that once an investment bubble of sufficient magnitude to affect a large part of the economy has been inflated, there is no way to let the air out of the bubble without wreaking economic havoc. To postpone the politically unacceptable economic havoc that would result from genuine deflation, every downturn must be met by progressively larger floods of new money. The endgame is hyperinflation and/or a reset involving the establishment of a new monetary system.

We think that the endgame is still many years away. In the meantime, be prepared for more waves of monetary inflation leading to increasingly obvious price inflation, interrupted by the occasional deflation scare.

Print This Post

Print This Post