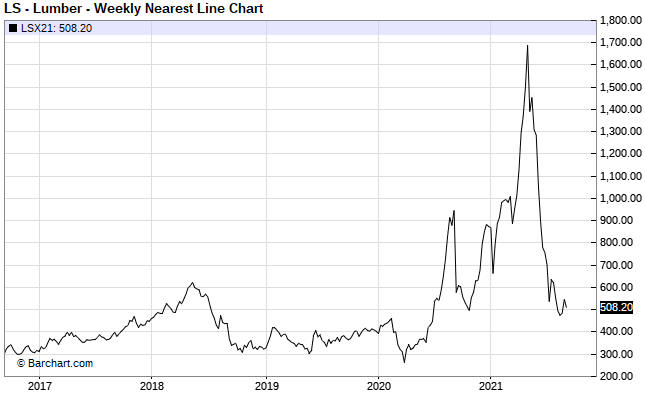

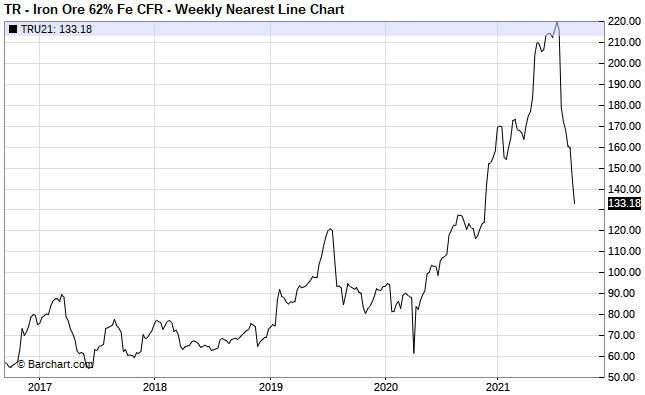

Over the past four months, in parallel with spectacular gains in the prices of coal and natural gas prices there have been spectacular declines in the prices of lumber and iron-ore. The following charts show the 70% crash in the lumber price from its May-2021 peak and the 40% crash in the iron-ore price from its July-2021 peak.

A common argument against there being a general inflation problem is that the large rises in commodity prices are due to temporary market-specific supply issues, leading to large price declines as soon as the supply issues are resolved. The plunges in the prices of lumber and iron-ore can be cited to support this argument.

There is an element of truth to this line of thinking. However, the same argument could have been made throughout the 1970s, in that every large commodity-price rise during that decade could be put down to a market-specific supply issue.

As long as the inflation doesn’t become ‘hyper’, that is, as long as the value of money doesn’t collapse relative to everything, a large and rapid rise in the price of a commodity will result in additional supply and/or reduced demand, eventually leading to a large price decline. This sequence of events played out in full in the lumber and iron-ore markets over the past 12 months and by the time we get to the middle of next year it likely will have played out in full in the natural gas and coal markets.

The clue that the price action has monetary roots is in its frequency, that is, in the number of markets that are experiencing huge price run-ups. Each huge price run-up in isolation can be put down to market-specific supply constraints, but when the same thing happens in so many different markets at different times within a multi-year period then we can be sure that the root cause is linked to the monetary system itself.

In the current environment, the root cause is the combination of rapid monetary inflation courtesy of the central bank and a huge increase in government deficit-spending. Thanks to the Fed, the supply of US dollars is about 50% greater today than it was two years ago. Thanks to the government, the newly-created money did a lot more than elevate the prices of financial assets.

Print This Post

Print This Post