[This blog post is a modified excerpt from a newsletter published at www.speculative-investor.com about two weeks ago]

The world is not going through a replay of the 1970s, as there are some critical differences between the current situation and the situation back then. For example, a critical difference is that private and government debt levels were much lower during the 1970s than they are today. However, this decade’s macroeconomic path probably will have a lot more in common with the 1970s than with any subsequent decade. One similarity is that just like the 1970s, the current decade probably will have multiple large waves of inflation. Another similarity and the one we will address now is the performance of the US yield curve.

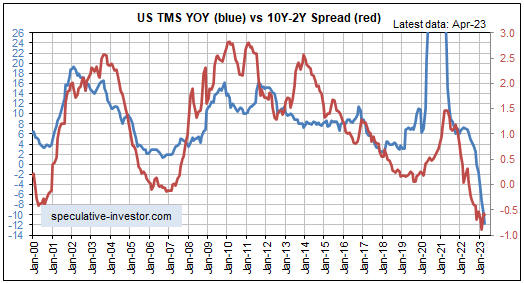

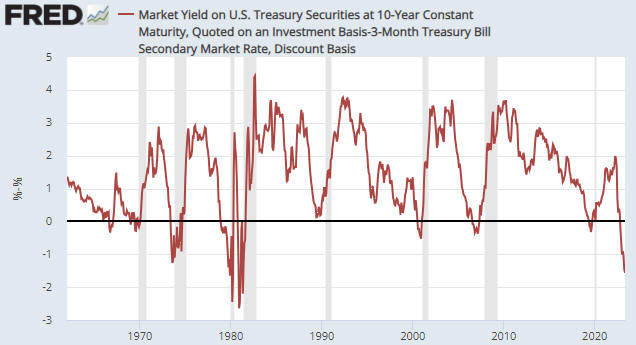

Here is a monthly chart of the US 10-year T-Note yield minus the 3-month T-Bill yield (the 10year-3month spread), a proxy for the US yield curve. Clearly, nothing like the current situation has occurred over the past forty years. Just as clearly, the current yield-curve situation is not unprecedented or even extreme compared to what happened during 1973-1981.

Note that the shaded areas on the chart show when the US economy was deemed by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) to be in recession.

During the period from June-1973 to August-1981, the yield curve was inverted for a cumulative total of 40 months (about 40% of the time). This means that during the aforementioned roughly 8-year period, yield curve inversion was almost the norm. Furthermore, there were times during this period when the inversion was more extreme than it is today.

Of potential relevance to the present, the 1973-1974 recession began 6 months after the yield curve became inverted and 3 months after the inversion extreme, that is, 3 months after the start of a steepening trend, while the 1981-1982 recession began 8 months after the yield curve became inverted and 7 months after the inversion extreme. The ‘odd man out’ was the 1980 recession, which began 13 months after the yield curve became inverted and 2 months BEFORE the inversion extreme. In other words, even during the major inflation swings of the 1970s and early-1980s, the yield curve tended to reverse from flattening/inverting to steepening prior to the start of an official recession.

Also of relevance is that during the 1970s gold generally did well when the yield curve (the 10year-3month spread) was inverted. For instance, the entire major rally from around $200 in late-1978 to the blow-off top above $800 in January-1980 occurred while the yield curve was inverted. In addition, the entire large decline in the gold price during 1975-1976 occurred while the yield curve was in positive territory.

The situation today is that the US yield curve (the 10year-3month spread) became inverted in October of last year. This means that about 8 months have gone by since the inversion. As mentioned above, the longest time from inversion to recession start during 1973-1981 was 13 months. Also, at this time there is no evidence that an inversion extreme is in place.

One conclusion is that based on what happened during the 1970s, we probably will have to get used to the yield curve being inverted. Another conclusion is that today’s inversion-recession path would remain within the bounds of what transpired during 1973-1981 if a recession were to begin by November of this year.

Print This Post

Print This Post