[This blog post is a modified excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

Financial market discussions and analyses often focus on fundamental issues that don’t matter, or at least don’t provide useful clues regarding the likely future performance of the market in question. A good example is the so-called “global US$ short position”, which is regularly cited in support of a bullish outlook for the US$.

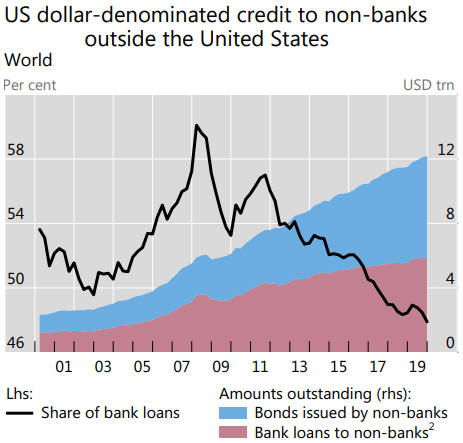

The argument is that the roughly $12 trillion of US$-denominated debt outside the US constitutes a short position that will create massive demand for dollars and thus put irresistible upward pressure on the Dollar Index (DX). There is an element of truth to the argument, but the “global US$ short position” always exists. It exists during US$ bull markets and it exists during US$ bear markets, because it is simply an effect of the US$ being the currency of choice for the majority of international transactions. Furthermore, the shaded area on the following chart shows that the quantity of dollar-denominated debt outside the US steadily increases over time and that even the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis resulted in only a minor interruption to the long-term trend. Consequently, the existence of this debt isn’t a major intermediate-term or long-term driver of the US dollar’s exchange rate.

Source: https://www.bis.org/statistics/gli2004.pdf

The element of truth to the “global US$ short position” argument is that a significant strengthening of the US currency relative to the currencies of other countries will increase the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt in those countries. This lessens the ability to borrow additional US dollars and puts pressure on existing borrowers to reduce their US$ obligations. In effect, it leads to some short covering that magnifies the upward trend in the US dollar’s exchange rate. This means that while the “global US$ short position” won’t be the cause of a strengthening trend in the US$, it can exacerbate such a trend.

We mentioned above that there is no empirical evidence that the “global US$ short position” drives trends in the US dollar’s exchange rate, but that doesn’t guarantee that the pile of US$-denominated debt outside the US won’t become an important exchange-rate driver in the future. The reason it won’t become important in the future is that prices are driven by CHANGES in supply and demand. The US$12T+ of foreign dollar-denominated debt represents part of the existing demand for dollars, meaning that the demand-related effects of this debt on the dollar’s exchange rate are ‘in’ the market already. At the same time, the total supply of dollars is growing rapidly.

At this point it’s worth addressing the idea that the Fed would be powerless to stop the US$ from appreciating if a major ‘debt deflation’ got underway. This is nonsense. Until the law of supply and demand is repealed, someone with the unlimited ability to increase the supply of something WILL have the power to reduce the price of that thing.

The Fed’s power to reduce the relative value of the US dollar was very much on display over the past few months. The financial-market panic and economic collapse of March-2020 predictably resulted in a desperate scramble for US dollars, leading to a fast rise in the Dollar Index. However, it took the Fed only two weeks to overwhelm the surging demand for dollars with a deluge of new dollar supply.

The upshot is that the so-called global US$ short position is not a valid reason to be a US$ bull.

With regard to performance over intermediate-term (3-18 month) time periods, the fundamentals that matter for the US$ are relative equity-market strength and interest rate differentials. This combination of drivers has been neutral for more than a year but soon could turn bearish for the US$.

Print This Post

Print This Post