[This blog post is a brief excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

The latest leading economic data indicate that the US recovery/expansion is intact and that US GDP will continue to grow at an above-average rate for at least two more quarters, albeit not as quickly as it grew during the first half of this year. Of particular relevance, the following monthly chart shows that the ISM Manufacturing New Orders Index (NOI), one of our favourite leading economic indicators, remains near the top of its 20-year range. The ISM NOI leads Industrial Production by 3-6 months.

Note that the GDP growth number for Q3-2021, the preliminary calculation of which will be reported late this month, could reveal substantial deceleration from the 6%-7% growth that was reported for the first two quarters of this year. In fact, it could be as low as 2%. However, the financial markets are aware of this and went at least part of the way towards discounting the slowdown over the past few months. More importantly, there’s a good chance that US economic activity will re-accelerate late this year and into the first quarter of next year. This will be partly due to inventory building but mainly due to millions of people re-entering the workforce (millions of people who were paid by the government NOT to produce are going to become productive due to the expiry, early last month, of the federal government’s $300/week unemployment subsidy).

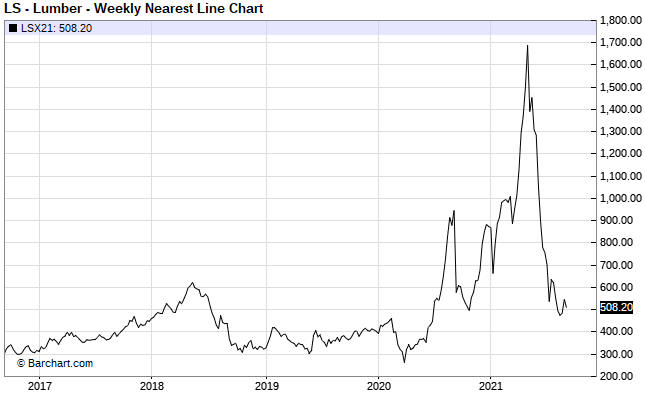

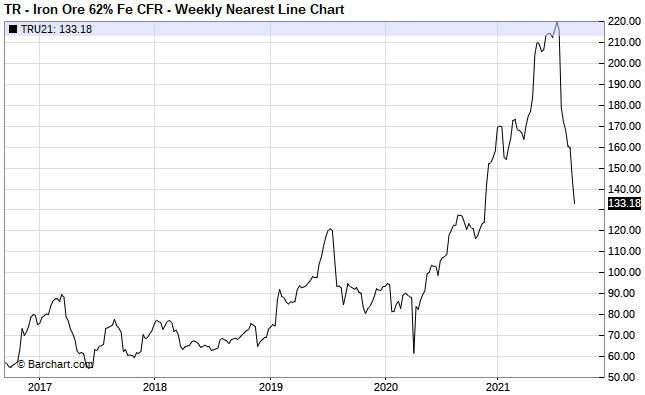

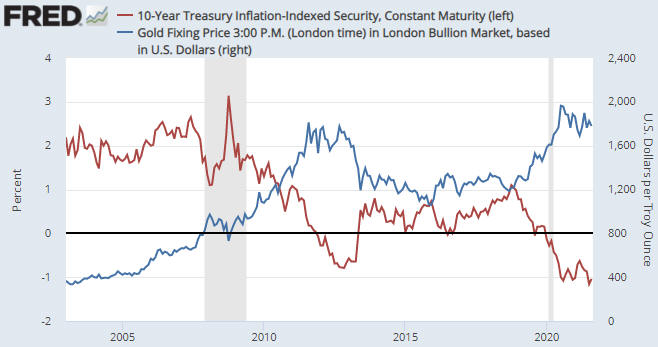

The performances of leading and coincident economic indicators show that the US economy remains in the boom phase of the boom-bust cycle, meaning that the economic landscape remains bullish for industrial commodities relative to gold. Consequently, the major upward trend in the commodity/gold ratio (GNX/gold) evident on the following chart should extend into next year.

In conclusion and as stated in previous commentaries over the past few months, the probability of the US economy re-entering recession territory prior to mid-2022 is extremely low, although current money-supply trends warn that a boom-to-bust transition and an equity bear market could begin as soon as the first half of 2022. This would suggest the second half of 2022 for the start of the next US recession, but there’s no point trying to look that far ahead. Our favourite leading indicators should give us ample warning.

Print This Post

Print This Post