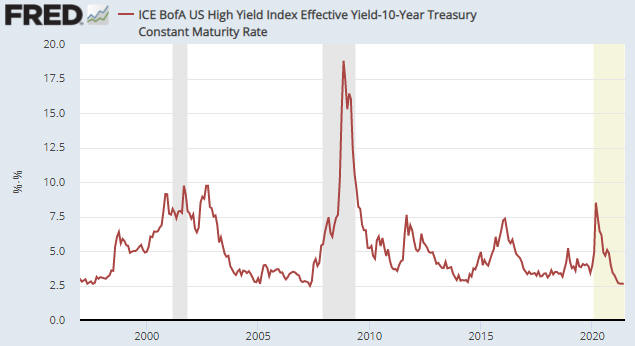

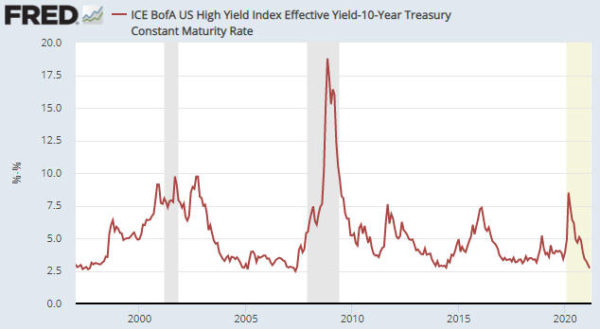

There are seven inputs to my Gold True Fundamentals Model (GTFM), one of which is an indicator of US credit spreads (a credit spread is the difference between the yield on a relatively high-risk bond and the yield on a relatively low-risk bond of the same duration). In a blog post on 12th April I wrote that if I had to pick just one fundamental to focus on at the moment, it would be credit spreads.

The average credit spread is the most reliable indicator of economic confidence. When economic confidence is high or in a rising trend, credit spreads will be narrow or in a narrowing trend. And when economic confidence is low or in a declining trend, credit spreads will be wide or in a widening trend. It therefore isn’t surprising that over the past 25 years there was a pronounced rise in US credit spreads prior to the start of every period of substantial weakness in the US economy and every substantial gold rally. This is as it should be.

Credit spreads being narrow or in a narrowing trend is a characteristic of an economic boom caused by creating lots of money out of nothing. In fact, the main reason for the popularity of inflation policy (pumping up the money supply) is that the policy initially leads to rising economic confidence as evidenced by narrowing credit spreads. It is only much later that the negative effects of the policy bubble to the surface, but by then enough time will have passed that the link between cause and effect will be obscured and the negative effects can be blamed on exogenous events as opposed to bad policy.

In my 12th April post I included a chart that showed a proxy for the average US credit spread. The chart’s message at the time was that credit spreads had been in a strong narrowing trend (reflecting rising economic confidence) for about 12 months and had become almost as low/narrow as they ever get. This implied that anyone who over the preceding several months had been betting on a large stock market decline or a large rally in the gold price had been betting against both logic and history. I pointed out that economic confidence was probably about as high as it would get, but that it could stay at a high level for more than a year.

An update of the same chart is displayed below. It shows that nothing has changed, in that over the ensuing period credit spreads essentially drifted sideways near their multi-decade lows. This means that the economic boom remains in full swing.

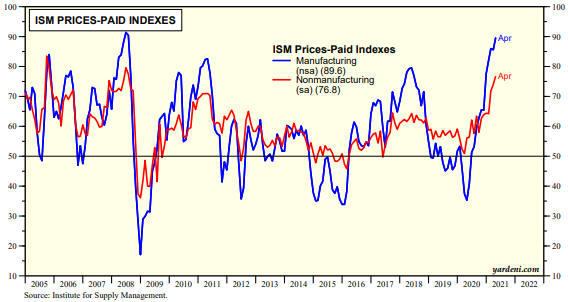

During an economic boom it isn’t a good idea to trade gold from the long side, except for the occasional multi-month trade after the gold market becomes ‘oversold’ in sentiment and momentum terms. However, if the economic boom is accompanied by rising inflation expectations and interest rates, as is the case with the boom that kicked off last year, it usually will pay to be long industrial commodities in general and energy in particular.

Print This Post

Print This Post