If you are asking the above question then your understanding of economics is sadly lacking or you are trying to mislead.

The Fed will never be completely out of monetary ammunition, because there is no limit to how much new money the central bank can create. The Fed will therefore always be capable of implementing some form of what Keynesians call stimulus. However, the so-called stimulus cannot possibly help the economy.

To believe that the central-bank monetisation of assets can help the economy you have to believe that an economy can benefit from counterfeiting. And to believe that the economy can be helped by lowering interest rates to below where they would otherwise be you have to believe that fake prices can be economically beneficial. In other words, you have to believe the impossible.

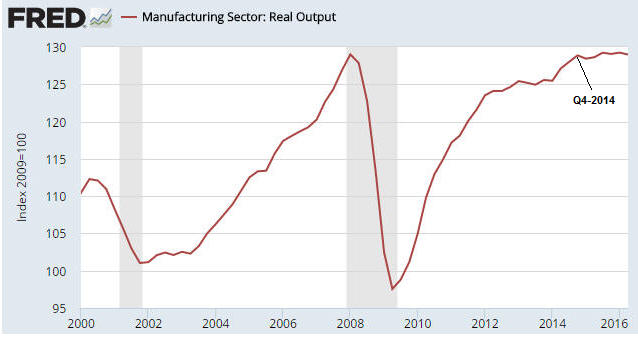

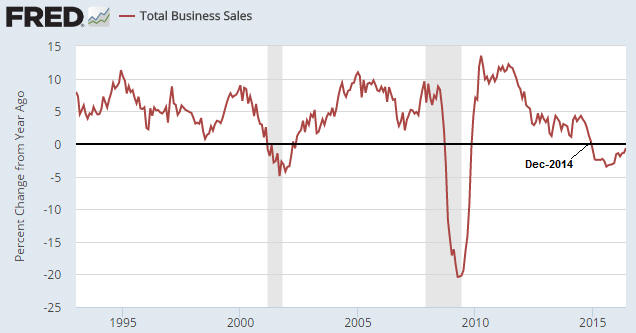

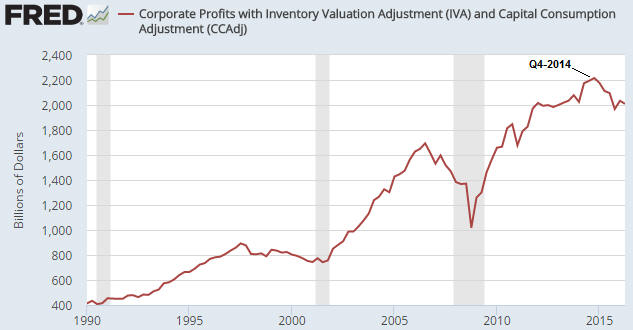

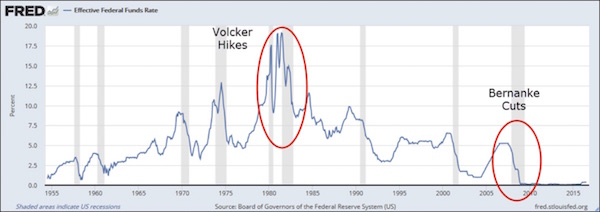

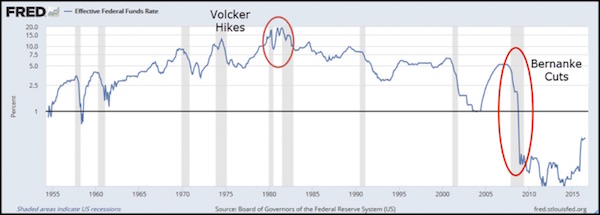

The reality is that the Fed never fights recession or helps the economy recover from recession, but it does cause recessions and gets in the way of genuine recovery after a recession occurs. For example, the monetary stimulus put in place by the Fed in response to the 2001 recession caused mal-investments — primarily associated with real estate — that were the seeds of the 2007-2009 recession. The price distortions caused by the Fed’s efforts to support the US economy from 2008 onward then firstly prevented a full liquidation of the mal-investments of 2002-2007 and then promoted a range of new mal-investments*. It’s therefore not a fluke that the most aggressive ‘monetary accommodation’ of the past 60 years occurred alongside the weakest post-recession recovery of the past 60 years. Moreover, the cause of the next recession will be the mal-investments stemming from the Fed’s earlier attempts to stimulate.

Unfortunately, if you have unswerving faith in a theoretical model that shows stronger real growth as the output following interest-rate cutting and/or money-pumping, then in response to economic weakness your conclusion will always be that interest-rate cutting and/or money-pumping is the appropriate course of action. And if the economy is still weak after such a course of action then your conclusion will naturally be that the same remedy must be applied with greater force.

For example, if cutting the interest rate to 1% isn’t followed by the expected strength then you will assume that the correct next step is to cut the interest rate to zero. If the expected growth still doesn’t appear then you will conclude that a negative interest rate is required, and if the economy stubbornly refuses to show sufficient vigor in response to a negative interest rate then your conclusion will be that the rate simply isn’t negative enough. And so on.

Whatever happens, the validity of the model that shows the economy being given a sustainable boost by central-bank-initiated monetary stimulus must never be questioned. After all, if doubts regarding the validity of the model were allowed to enter mainstream consciousness then people might start to ask: Should there be a central bank?

Circling back to the question posed at the top of this blog post, the question, itself, is a form of propaganda in that it presupposes the validity of the stimulus model (it presumes that the Fed is genuinely capable of fighting a recession, which it patently isn’t). Anyone who asks the question is therefore either a deliberate promoter of dangerous propaganda or a victim of it.

*Examples of the mal-investments promoted by the Fed’s money-pumping and interest-rate suppression during the past several years include the favouring by corporate America of stock buybacks over capital investment, the debt-funding of an unsustainable shale-oil boom, a generally greater amount of risk-taking by bond investors as part of a desperate effort to obtain a real yield above zero, the large-scale extension of credit to ‘subprime’ borrowers to artificially boost the sales of new cars, and the debt-funded investing in college degrees for which there is insufficient demand in the marketplace (a.k.a. the student loan scam).

Print This Post

Print This Post