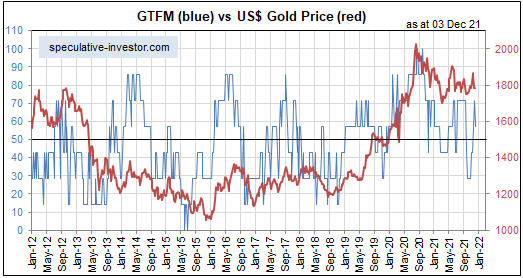

According to my Gold True Fundamentals Model (GTFM), the gold market’s fundamentals were bullish or trending positively from early-November of 2019 through to late-September of 2020 and were bearish or trending negatively from early-October of 2020 through to late-October of this year. As illustrated by the blue line on the following weekly chart, they turned upward in early-November and are now in bullish territory, albeit only slightly. Does the recent upturn constitute a major shift or a countertrend move within an overall environment that remains bearish for gold?

Before attempting to answer the above question, it is worth reiterating that I use the term “true fundamentals” to distinguish the fundamentals that actually matter from the largely irrelevant issues that many gold-market analysts and commentators focus on.

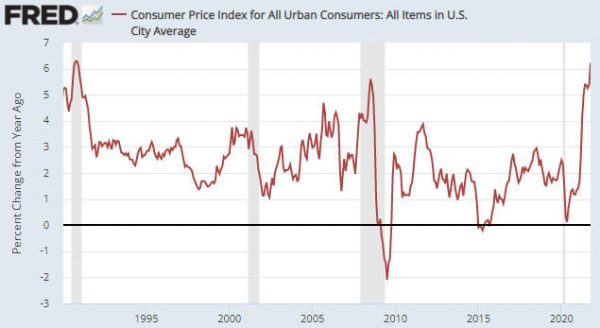

According to many pontificators on the gold market, gold’s fundamentals include the volume of metal flowing into the inventories of gold ETFs, China’s gold imports, the amount of “registered” gold at the Comex, India’s monsoon and wedding seasons, jewellery demand, the amount of gold being bought/sold by various central banks, changes in mine production and scrap supply, changes in the money supply and the CPI, and wild guesses regarding the activities of bullion banks. These things are distractions at best. For example, a gold investor/trader could have ignored everything that has been written over the past 20 years about the amount of gold in Comex warehouses and been none the worse for it.

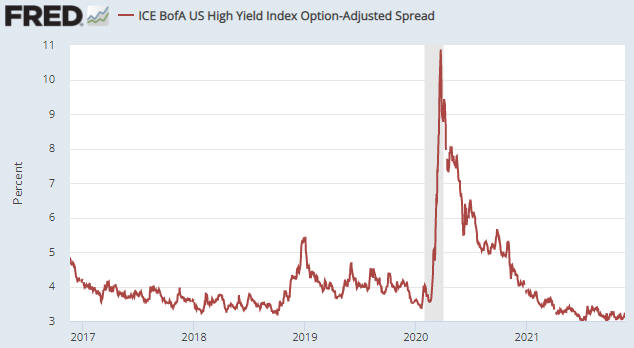

On an intermediate-term (3-18 month) basis, there is a strong tendency for the US$ gold price to trend in the opposite direction to confidence in the US financial system and economy. That’s why most of the seven inputs to my GTFM are measures of confidence. Two examples are credit spreads and the relative strength of the banking sector. The model is useful, in that over the past two decades all intermediate-term upward trends in the gold price occurred while the GTFM was bullish most of the time and all intermediate-term downward trends in the gold price occurred while the GTFM was bearish most of the time.

However, upward corrections can occur in the face of bearish fundamentals and downward corrections can occur in the face of bullish fundamentals. For example, there was a substantial downward correction in the gold market in March of 2020 in the face of bullish fundamentals. Such corrections often are signalled by sentiment indicators.

Getting back to the question posed in this post’s opening paragraph, I suspect that we are dealing with a countertrend bullish move within an overall environment that remains bearish for gold. The reason is that although a couple of small cracks have appeared in the superficially-positive economic picture over the past few weeks, the preponderance of evidence still indicates that the US economic boom (monetary-inflation-fuelled increase in economic activity) is intact.

Major gold rallies occur during the economic bust and boom-to-bust transition phases of the long-term cycle. By the same token, gold tends to fare poorly, especially relative to the broad stock market and industrial commodities, during the boom phases of the long-term cycle. While the boom remains intact, the best that can be reasonably expected from gold is a multi-month rebound within a trading range or a long-term downward trend.