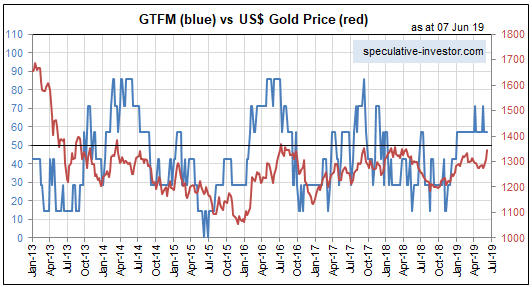

After spending almost all of 2018 in bearish territory, gold’s true fundamentals* (as indicated by my Gold True Fundamentals Model – GTFM) have spent all of this year to date in bullish territory. Refer to the following chart comparison of the GTFM (the blue line) and the US$ gold price (the red line) for the details.

A market’s true fundamentals are akin to pressure. Due to sentiment and other influences a market can move counter to the fundamentals for a while, but if the fundamentals continue to act in a certain direction then the pressure will build up until the price eventually falls into line. Also, even if it isn’t sufficient to bring about a significant rally, the upward pressure stemming from a bullish fundamental backdrop will tend to create a price floor. That’s what happened with gold during March and April.

As was the case when I last addressed this topic at the TSI Blog, the most important GTFM input that is yet to turn bullish is the yield curve (as indicated by the 10year-2year and 10year-3month yield spreads). This input shifting from bearish to bullish requires a reversal in the yield curve from flattening (long-term rates falling relative to short-term rates) to steepening (long-term rates rising relative to short-term rates). If the reversal is driven primarily by falling short-term interest rates it indicates a boom-to-bust transition, such as occurred in 2000 and 2007, whereas if the reversal is driven primarily by rising long-term interest rates it points to increasing inflation expectations.

As illustrated below, at the end of last week there was no evidence of such a trend change in the 10year-3month yield spread.

To get a gold bull market there probably will have to be a sustained trend reversal in the yield curve. I think that will happen during the second half of this year, but it hasn’t happened yet. Also, when it does happen my guess is that it will be driven by rising long-term interest rates (indicating rising inflation expectations), not falling short-term interest rates. That’s an out-of-consensus view right now, because inflation expectations are low/falling and almost everyone has come to the conclusion that an aggressive Fed rate-cutting campaign will get underway in the near future.

Another GTFM input that could shift from bearish to bullish in the near future and thus add to the upward pressure on the gold price is the currency exchange rate input. At the moment, all it would take to bring about this shift is a weekly close in the Dollar Index about half a point below last week’s close.

My guess is that there will be some corrective activity in the gold market over the coming 1-2 weeks, but as long as the GTFM stays in bullish territory the fundamentals-related upward pressure should enable the gold price to make new multi-year highs within the next few months.

*I use the term “true fundamentals” to distinguish the actual fundamental drivers of the gold price from the drivers that are regularly cited by gold-market analysts and commentators. According to many pontificators on the gold market, gold’s fundamentals include the volume of metal flowing into the inventories of gold ETFs, China’s gold imports, the volume of gold being transferred out of the Shanghai Futures Exchange inventory, the amount of “registered” gold at the COMEX, India’s monsoon and wedding seasons, jewellery demand, the amount of gold being bought/sold by various central banks, changes in mine production and scrap supply, and wild guesses regarding JP Morgan’s exposure to gold. These aren’t true fundamental price drivers. At best, they are distractions.

Print This Post

Print This Post