[This blog post is an excerpt from a commentary published at speculative-investor.com last week]

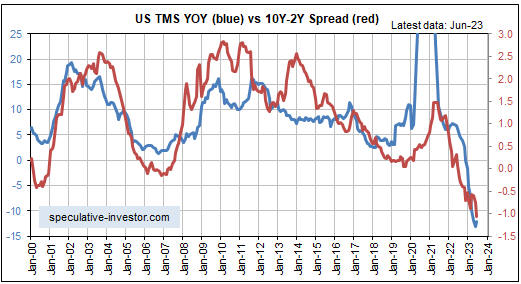

The year-over-year rate of growth in US True Money Supply (TMS) ticked upward in June, that is, the US money supply contracted at a slightly slower pace during the latest month for which there are monetary data. Although the uptick is barely noticeable on the following chart, it is probably significant. It is the first increase in the monetary inflation rate since March-2022 and probably marks an end to the decline.

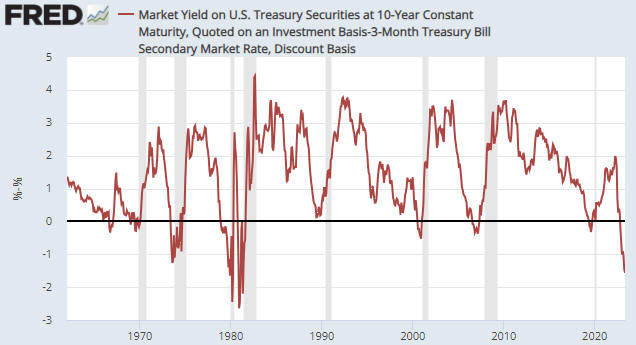

Below is our chart comparing the US monetary inflation rate (the blue line) with the 10y-2y yield spread (the red line), a proxy for the US yield curve. The monetary inflation rate drives the yield curve, so if the monetary inflation rate has begun to trend upward then the yield curve should commence a steepening trend within the next couple of months.

Both the monetary inflation rate and the yield curve may have reached their negative extremes, but unless one of two things happens the US will experience monetary deflation and the yield curve will remain inverted until at least the end of this year. This is because even if the Fed has made its final rate hike, it plans to continue its Quantitative Tightening (QT) for many months to come.

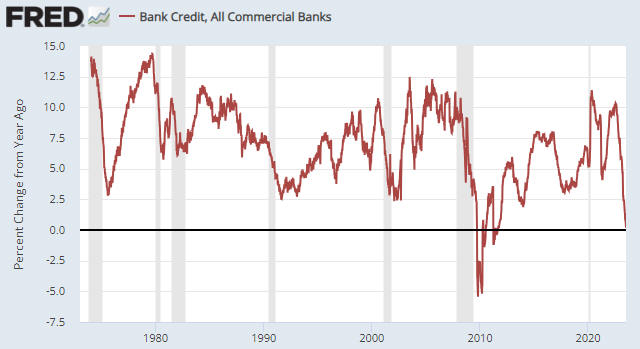

Continuing the QT program at the current rate would remove about $380B from the money supply over the remainder of this year. Although this could be offset by commercial bank lending (commercial banks create new money when they make loans), trends in the commercial banking industry currently are heading in the opposite direction, that is, banks are becoming less willing to expand credit.

One of the two things that could shift the monetary trend from deflation to inflation over the next several months is the large-scale exodus of money from the Fed’s Reverse Repo (RRP) facility. There is still about $1.7 trillion ‘sequestered’ in this facility, which means that there is the potential for up to $1.7T to be released from RRPs to the economy’s money supply.

The other development that could return the US money supply to inflation mode is a crisis that not only stops the Fed’s QT, but also precipitates a new bout of QE.

Our expectation is that there will not be a genuine crisis between now and the end of this year, but that there will be sufficient weakness in the stock market to prompt the Fed to end QT and that at least $1T will come out of the RRP facility to take advantage of the higher rates being offered by Treasury bills. This combination probably would turn the US monetary inflation rate positive by year-end and set in motion a steepening trend in the US yield curve.

Print This Post

Print This Post