[This blog post is an excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

The Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) holds that the change in money Purchasing Power (PP) is proportional to the change in the Money Supply (MS). It’s a bad theory, because it doesn’t reflect reality.

There are three main reasons that QTM doesn’t work in the real world, the first being that money PP can’t be expressed as a single number. There is no such thing as the “general price level”. Instead, at any point in time there are millions of individual prices that cannot be averaged to arrive at something sensible. That being said, QTM wouldn’t work even if it were possible to determine the “general price level”.

The second reason that QTM doesn’t work in the real world is that new money never gets injected uniformly throughout the economy. A consequence is that different prices get affected in different ways at different times, depending on who the first receivers of the new money happen to be. For example, during normal times the commercial banks are responsible for almost all money creation, with new money entering the economy via loans to the banks’ customers, whereas during 2008-2014 most new US dollars were created by the Fed and injected into the financial markets via the purchasing of bonds.

However, even if there existed a single number that accurately represented money PP and new money was injected uniformly throughout the economy, the Quantity Theory of Money STILL wouldn’t work. The reason is that as is the case with the price of anything, the price of money is determined by supply AND demand. (As an aside, in the real world there is no such thing as money velocity.) In other words, the price (PP) of money never could be properly explained/understood by reference to only the supply of money. We’ll now expand on this point.

Over the very long term, changes in money supply dominate changes in money demand, where by money demand we mean the desire to hold cash as an asset rather than the desire to obtain money to facilitate current purchases. However, during periods of up to a few years the change in money demand often will dominate the change in money supply. A good example is September 2008 through to March 2009. During this period the Fed rapidly increased the money supply, but the Fed’s actions were overwhelmed by increasing demand for money. Furthermore, when prices suddenly started rising in March-April of 2009 it was not only because the money supply had grown, but also because the demand for money had begun to fall.

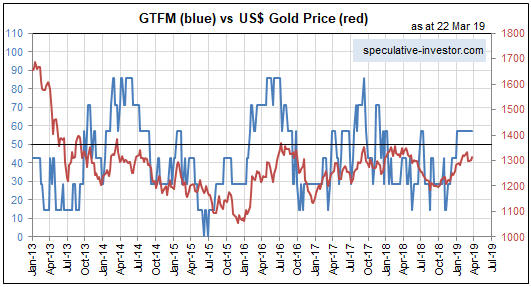

In relation to the above it’s important to understand that in addition to affecting the supply of money, the Fed and other central banks affect the demand for money. This is very relevant to the recent past. Over the past three months the Fed continued to reduce the money supply, but statements emanating from the Fed had the effect of reducing the desire to hold cash. The net effect was a general increase in ‘liquidity’ even while the Fed acted to reduce the money supply.

Unfortunately, there is no way to analyse the monetary situation that is both simple and accurate. In particular, there is no simple equation that indicates the real-world relationship between money supply and money purchasing-power.

Print This Post

Print This Post