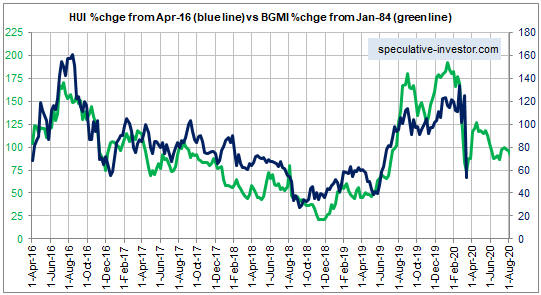

In a blog post three weeks ago, I mentioned that in TSI commentaries over the past year I had been tracking the current performance of the gold mining sector (as represented by the HUI) with its performance during the mid-1980s (as represented by the Barrons Gold Mining Index – BGMI). The 1980s comparison predicted the big moves that have occurred since May of last year, including the Q1-2020 crash. I concluded the earlier post with the comment: “History informs us that after a crash comes a rebound and after a rebound there is usually a test of the crash low.”

Here is an update of the weekly chart that I have been showing at TSI for almost a year. The latest price shown for the HUI is last week’s close. The chart suggests that the obligatory post-crash rebound is almost complete and that the next move of consequence will be a decline to test the March low.

If a test of the March low occurs, it should be successful (it’s highly probable that the gold mining indices and ETFs made their bottoms for the year last month). However, with regard to future outcomes there is always more than one realistic possibility. For example, although the historical record suggests that a test of the March low will happen within the next two months, a more bullish short-term outcome is possible.

Parameters that could be used to indicate that a different short-term scenario was playing out have been mentioned at TSI, but at this stage I think the odds favour a test of the crash low for pretty much everything that has crashed, including the gold sector. Looking beyond the short-term, I expect that the major fundamental differences between the late-1980s and the present will assert themselves during the second half of this year and cause the current market for gold mining stocks to diverge (in a bullish way) from the 1980s path.

Print This Post

Print This Post