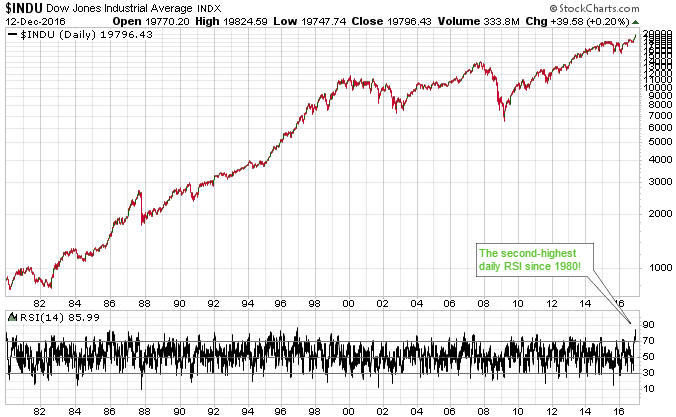

By one measure, the Dow Industrials Index is now at its second-most ‘overbought’ level since 1980. The measure I’m referring to is the 14-day RSI (Relative Strength Index), a short-term momentum oscillator shown in the bottom section of the following Dow chart.

Being the most something-or-other (the most overbought/oversold, optimistic/pessimistic, etc.) since a distant past time often isn’t as important as it sounds. For instance, the only time since 1980 that the Dow’s daily RSI(14) was as high as it is today was in November of 1996 (interestingly, almost exactly 20 years ago), but nothing dramatic happened during the days, weeks or months that followed the November-1996 momentum extreme.

As illustrated below, a pullback to the 50-day moving average (MA) got underway within a few days of the momentum extreme, after which the Dow resumed its long-term advance. There was a more significant short-term pullback (to the 200-day MA) a few months later and an intermediate-term correction a few months after that (more than 8 months after the momentum extreme), but the bull market continued for another 3 years.

A short-term momentum extreme occurred at the price peak that was followed by the October-1987 stock market crash, but it is a lot more common for such extremes to be followed by nothing more serious than a routine multi-week correction. With measures of market breadth pointing to a 6-12 month extension of the bull market we probably won’t get anything more bearish than a routine multi-week correction within the next couple of months, although I admit that the near-vertical rally since the Presidential Election has me ‘on edge’.

Print This Post

Print This Post