I discussed the relationship between gold and inflation expectations a couple of times in blog posts last year (HERE and HERE). Contrary to popular opinion, gold tends to perform relatively poorly when inflation expectations are rising and relatively well when inflation expectations are falling.

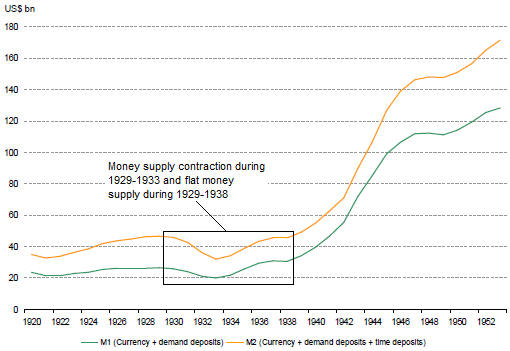

The relationship is illustrated by the chart displayed below. The chart shows that over the past seven years there has been a strong positive correlation between RINF, an ETF designed to move in the same direction as the expected CPI, and the commodity/gold ratio (the S&P Spot Commodity Index divided by the US$ gold price). In other words, the chart shows that a broad basket of commodities outperformed gold during periods when inflation expectations were rising and underperformed gold during periods when inflation expectations were falling.

This year, inflation expectations crashed during February-March in reaction to the draconian economic lockdowns imposed by governments and then recovered after central banks and governments tried to mitigate the lockdown-related devastation by showering the populace with money. This resulted in a crash in the commodity/gold ratio early in the year followed by a rebound in commodity prices relative to gold beginning in April.

The above chart shows that the rebound in the commodity/gold ratio from its April-2020 low was much weaker than the rebound in inflation expectations. This happened because there are forces in addition to inflation expectations that act on the commodity/gold ratio and some of these forces have continued to favour gold over commodities. Of particular relevance, the rise in inflation expectations has been less about optimism that another monetary-inflation-fuelled boom is being set in motion than about concerns that a) the official currency is being systematically destroyed and b) the private sector’s ability to produce has been curtailed on a semi-permanent basis.

Inflation expectations probably will continue to trend upward over the coming 12 months and this should lead to additional strength in industrial commodities relative to gold, but less strength than implied by the relationship depicted above. It probably will happen this way because more and more economic activity will be associated with government spending, which does nothing for long-term progress.

Eventually the relationship depicted above will be turned on its head due to plummeting confidence in both the government and the central bank, that is, at some point rising inflation expectations will start being associated with an increase in the perceived value of gold relative to commodities and pretty much everything else.