A bullish divergence between the gold-mining sector of the stock market, as represented by the HUI and/or the XAU, and gold bullion involves the gold-mining sector having an upward bias while gold bullion has a downward bias or the gold-mining sector making a higher low while the bullion market makes a lower low. However, bullish divergences often don’t happen around major price bottoms. In fact, it is not uncommon for a major price bottom in gold-related investments to be preceded by a bearish divergence between the gold-mining indices and the metal. To be more specific, it is not uncommon for the gold-mining indices to be weak relative to gold bullion right up to the ultimate price bottom, at which point they suddenly become relatively strong.

Here are charts showing two historical examples of what I am referring to, either of which could be relevant to the present situation. The first chart shows the continuing downward bias in the XAU along with an upward bias in the US$ gold price in the weeks leading up to the XAU’s July-1986 bottom. The July-1986 bottom was followed by a huge multi-quarter rally in the gold-mining sector. The second chart shows the relentless decline in the HUI along with a flat gold price in the weeks leading up to the HUI’s November-2000 bottom. The November-2000 bottom was also followed by a huge multi-quarter rally in the gold-mining sector. The rally from the July-1986 bottom turned out to be the bear-market variety whereas the rally from the November-2000 bottom turned out to be the first leg of a new bull market, but from a practical speculation perspective an X% gain in a bear market is just as good as an X% gain in a bull market.

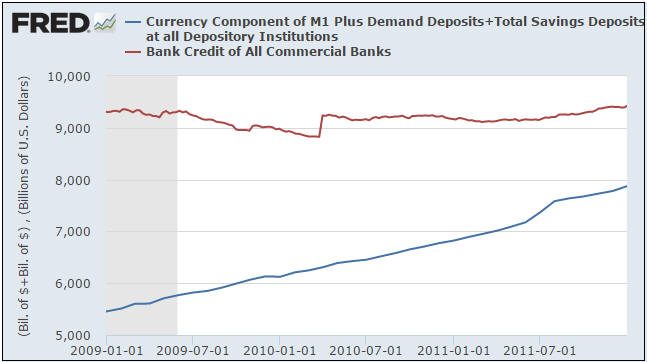

For comparison purposes, here is a chart showing the present situation.

It’s obviously too soon to know if the 10th August rebound in the gold-mining sector marked the start of a multi-quarter rally or even a 1-2 month rally, but the potential is there.

Print This Post

Print This Post