[The following discussion is a slightly-modified excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

It’s important to state up front that despite the associated pitfalls, it can definitely be helpful to track the public’s sentiment and use it as a contrary indicator. This is because most participants in the financial markets get swept up by the general mood. They end up buying into the idea that prices are bound to go much higher despite valuations having already become unusually high or the idea that prices will continue to slide despite current valuations being unusually low. This causes them to be very optimistic near important price tops and either very pessimistic or totally disinterested near important price bottoms.

It will always be this way because 1) a major price/valuation trend can’t end until the fundamental story behind the trend has been fully embraced by ‘the public’, and 2) the public’s own buying/selling shifts the probability of success. For example, when the public gets enthusiastic about an investment its own buying pushes up the price of the investment to the point where future performance is guaranteed to be poor. Consequently, there is no chance that the investing public can ever collectively enter or exit any market at an opportune time.

There are, however, three potential pitfalls associated with using sentiment to guide buying/selling decisions.

The first is linked to the reality that sentiment generally follows price, which makes it a near certainty that the overall mood will be at an optimistic extreme when the price is near an important top and a pessimistic extreme when the price is near an important bottom. The problem is that while an important price extreme will always be associated with a sentiment extreme (extreme optimism at a price high and extreme pessimism at a price low), a sentiment extreme doesn’t necessarily imply an important price extreme. For example, if the price of an investment has been trending strongly upward for many months and is at an all-time high then sentiment indicators will almost certainly reveal great optimism even if the upward trend is still in its infancy. It is therefore dangerous to take large positions based solely on sentiment.

The second potential pitfall associated with using sentiment to guide buying/selling decisions is that what constitutes a sentiment extreme will vary over time, meaning that there are no absolute benchmarks. Of particular relevance, what constitutes dangerous optimism in a bear market will often not be a problem in a bull market and what constitutes extreme fear/pessimism in a bull market will often not signal a good buying opportunity in a bear market. In other words, context is critical when assessing sentiment. Unfortunately, the context is always a matter of opinion.

The third potential pitfall relates to the sentiment indicators that are based on surveys.

Regardless of what the surveys say, there will always be a lot of bears and a lot of bulls in any financial market. It must be this way otherwise there would be no trading and the market would cease to function. As a consequence, if a survey shows that almost all traders are bullish or that almost all traders are bearish it means that the survey has a very narrow focus. In other words, the survey must be dealing with only a small fragment of the overall market.

There is no better example of sentiment’s limitations as a market timing indicator than the US stock market’s performance over the past few years. To show what I mean I’ll use the results of the sentiment survey conducted by Investors Intelligence (II), which has the longest track record* and is probably the most accurate of the stock market sentiment surveys.

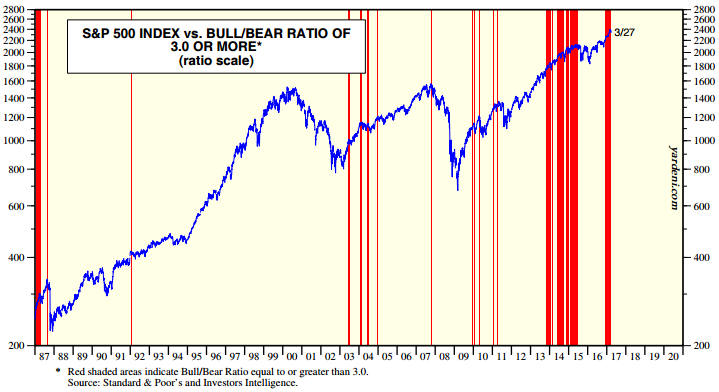

The following chart from Yardeni.com shows the performance of the S&P500 Index (SPX) over the past 30 years with vertical red lines to indicate the weeks when the II Bull/Bear ratio was at least 3.0 (a bull/bear ratio of 3 or more suggests extreme optimism within the surveyed group).

Notice that vertical red lines coincided with most of the important price tops (the 2000 top was the big exception), but that there were plenty of times when a vertical red line (extreme optimism) did not coincide with an important price top. Notice, as well, that optimism was extreme almost continuously from Q4-2013 to mid-2015 and that following a correction the optimistic extreme had returned by late-2016.

In effect, sentiment has been consistent with a bull market top for the past 3.5 years, but there is not yet any evidence in the price action that the bull market has ended.

The bottom line is that sentiment can be a useful indicator, but it does have serious limitations. It is just one medium-sized piece of a large puzzle.

*The II sentiment data goes back to 1963

Print This Post

Print This Post