The following charts relate to an update on the markets that was just emailed to TSI subscribers.

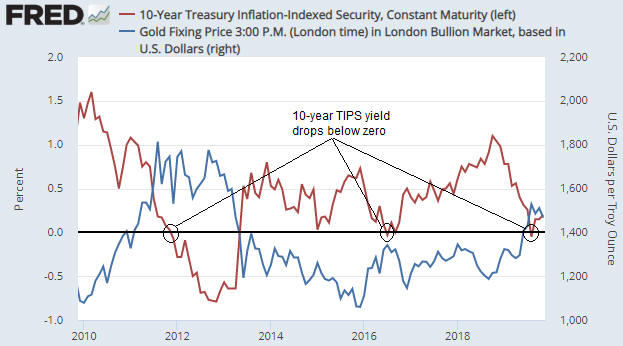

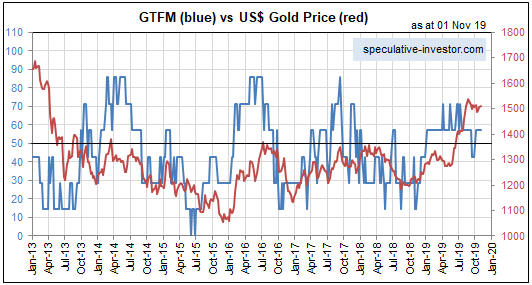

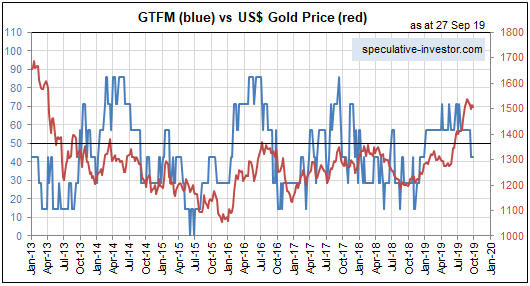

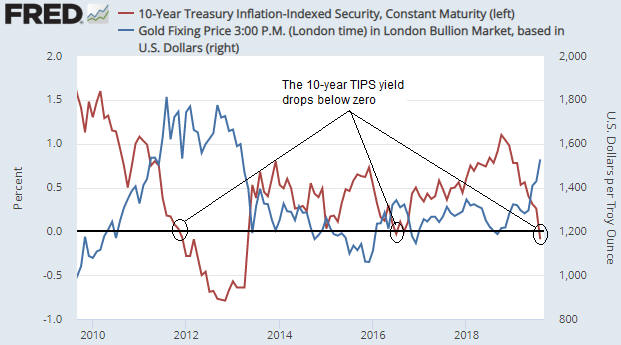

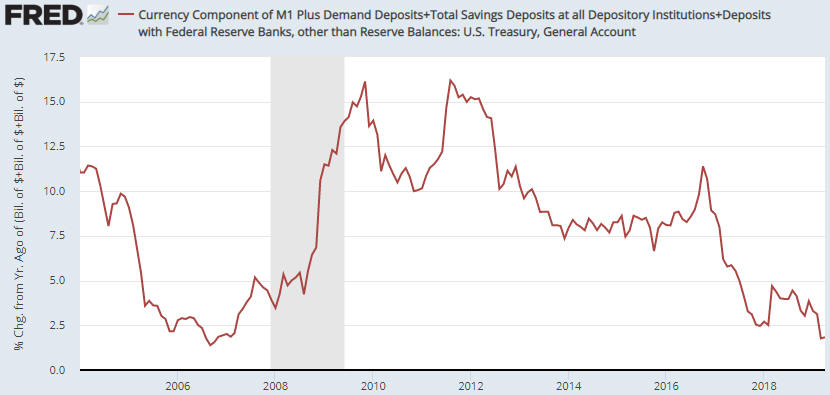

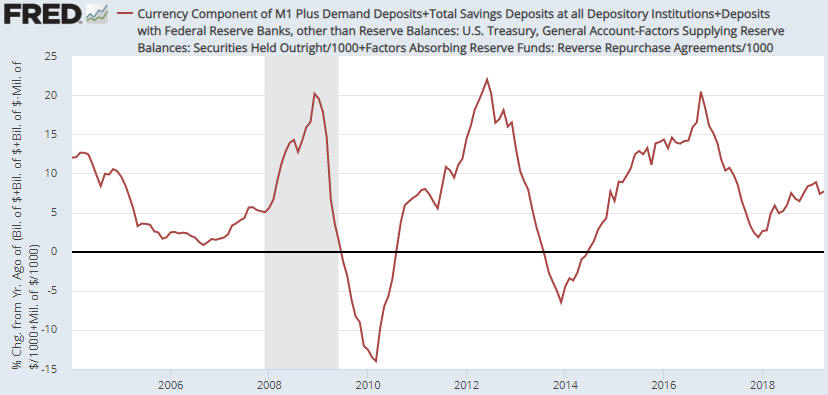

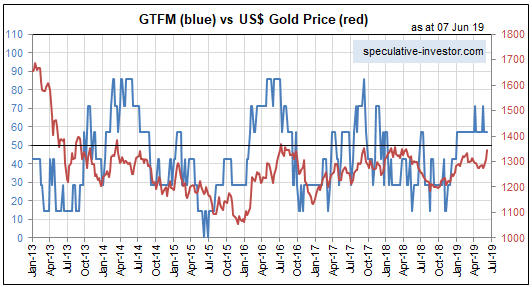

1) Gold

2) The Gold Miners ETF (GDX)

3) The Yen

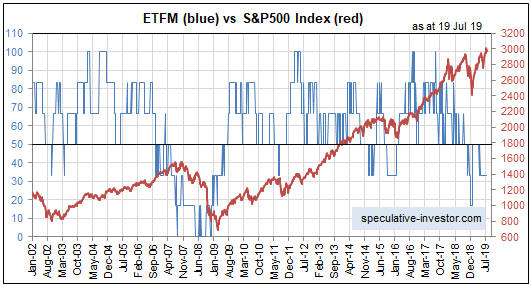

4) The S&P500 Index (SPX)

5) The Russell2000 ETF (IWM)

6) The Dow Transportation Average (TRAN)

7) The iShares 20+ Year Treasury ETF (TLT)

Print This Post

Print This Post