[This blog post is an excerpt from a commentary at www.speculative-investor.com]

We haven’t discussed global monetary inflation for a while, mainly because very little was happening and what was happening was having minimal effect on asset prices or economic performance. However, the global money-supply situation is now noteworthy.

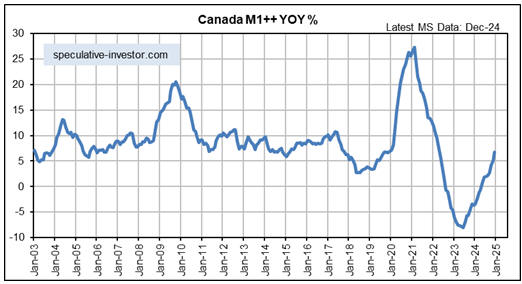

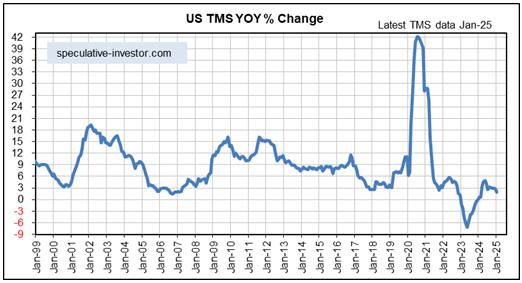

First of all, attempts to reflate clearly are being made in some parts of the world. From our perspective, the most significant of these attempts are evident in the following monthly charts showing the monetary inflation rates in Australia and Canada. In both cases, year-over-year (YOY) money-supply growth rates have rebounded strongly from negative territory (monetary deflation territory, that is) to around 7%. These rebounds are setting the scene for economic booms, but we suspect that the booms won’t start until next year and that in the meantime there will be more economic weakness.

However, in the world’s most influential economies/regions there is no evidence, yet, that a concerted attempt to reflate is underway. In particular:

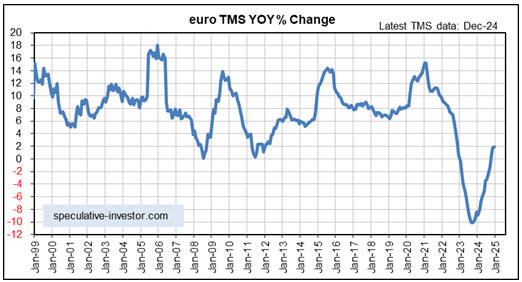

1. The following charts show that although the money-supply growth rates of both the US and the euro-zone have rebounded from the deep deflationary levels of 2023, the current levels (around 2%) are very low by historical standards. The current levels have tended to be associated with recessions and/or credit crises, not booms.

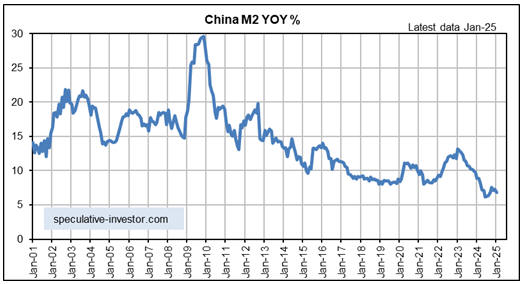

2. The next chart shows that while China’s YOY M2 growth rate remains moderately high by Western standards, it is near a multi-decade low. This means that the monetary stimulus introduced last September in China is yet to have a discernible effect on monetary conditions.

By the way, normally we show China’s M1 growth rate rather than its M2 growth rate, but the PBOC changed its M1 calculation methodology in January-2025 and in doing so made comparisons with previous months/years impossible. As far as we can tell, China’s M1 is roughly unchanged over the past year.

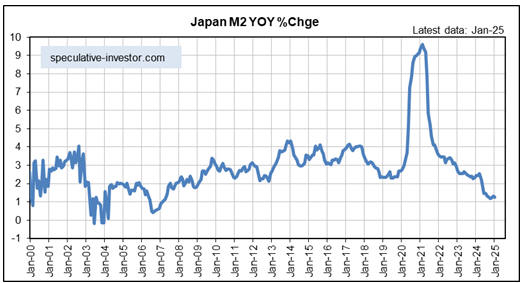

3. Our final chart shows that Japan’s YOY M2 growth rate is near an 18-year low, so the BOJ’s concern about price inflation in Japan is leading to tight monetary conditions. These tight monetary conditions probably will lead to economic weakness, much lower price inflation levels and additional Yen strength over the next 12 months, prompting the BOJ to return to its pro-inflation ways. Like all central banks, the BOJ is adjusting monetary policy based on what it sees in the rearview mirror.

The combination of the malinvestment that occurred in response to the massive monetary inflation of 2020-2022 and the current low levels of monetary inflation in the world’s most important economies increases the risk that the world is heading towards a period of widespread economic weakness.