In a blog post on 31st March I argued that MMT (Modern Monetary Theory) had been surreptitiously put into practice in the US. However, according to a quote from Lacy Hunt (Hoisington Investment Management) included by John Mauldin in a recent letter, what the Fed and the US government are doing doesn’t qualify as MMT.

According to Lacy Hunt: “For the Fed to engage in true MMT, a major regulatory change to the Federal Reserve Acts would be necessary: The Fed’s liabilities would need to be made legal tender. Having the Treasury sell securities directly to the Fed could do this; the Treasury’s deposits would be credited and then the Treasury would write checks against these deposits. In this case, the Fed would, in essence, write checks to pay the obligations of the Treasury. If this change is enacted, rising inflation would ensue and the entire international monetary system would be severely destabilized and the US banking system would be irrelevant.”

One problem with Lacy Hunt’s argument is that some of the Fed’s liabilities are already legal tender and have been for a very long time. I’m referring to the $1.9 trillion of “Currency in circulation” (physical notes and coins). This currency sits on the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet. Also, the money that the US Treasury spends comes from the Treasury General Account, which also sits on the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Admittedly, the Fed currently does not buy Treasury debt directly. Instead, it acts through Primary Dealers (PDs). The PDs buy the debt from the government and the Fed buys the debt from the PDs. When this happens, new money is credited by the Fed to the commercial bank accounts of PDs and thus becomes a liability of the private banking system. At the same time, the private banks are ‘made whole’ by having new reserves added to their accounts at the Fed.

In other words, rather than money going directly from the Fed to the Treasury General Account (TGA), under the current way of doing things the money gets to the same place indirectly via PDs. This enables the commercial banking system to get its cut, but from both the government’s perspective and the money supply perspective there is no difference between the Fed directly buying government debt and the Fed using intermediaries (PDs) to do the buying.

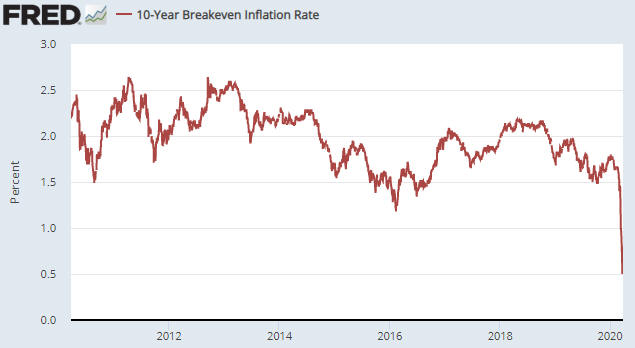

Now, the Fed’s QE programs of 2008-2014 generated a lot less “price inflation” than many people feared. This was largely because the new money was injected into the financial markets (bonds and stocks) and only gradually trickled into the ‘real economy’. To some extent what happened over the past couple of months is similar, but with two significant differences.

One significant difference between the Fed’s recent actions and the QE of 2008-2014 is that for some of its new money and credit creation the Fed is bypassing the PDs. No regulatory change was needed for this to happen. Instead, as I explained in my earlier post, the Fed created Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) that do the actual monetising of assets and the lending of new money into existence. In effect, new money is now being created by the Fed and sent directly to various non-bank entities, including municipalities, private businesses and bondholders.

The second significant difference is the crux of the issue and why the US now has MMT in all but name.

You see, the essence of MMT isn’t the mechanical process via which money gets to the government. The essence is the concept that the government is only limited in its money and debt creation by “inflation”. The idea is that until “inflation” becomes a problem, the government can create as much new money and debt as it wants as part of an effort to achieve full employment. A related idea is that government spending does not have to be financed by taxation.

Is there really any doubt that the US government no longer feels constrained in its creation of debt, the bulk of which is being purchased indirectly using new money created by the Fed? After all, in the space of less than two months the US federal government has blown-out its expected annual deficit from around $1T to around $4T and is talking about massive additional spending/borrowing increases to support the economy. Clearly, no senior politician from either of the main parties is giving any serious thought to how this debt will be repaid or the future implications of the deficit blow-out.

The bottom line is that the US doesn’t have MMT in law, but it does have MMT in fact.