[This blog post is an excerpt from a commentary posted at TSI last week]

We assume that everyone reading this has at least superficial knowledge of the incredible goings-on around the stock of GameStop (GME), a video game retailer. The GME situation became so extraordinary last week that it drew the attention of senior US policymakers, but more importantly it is representative of what’s happening throughout the stock market and is symptomatic of the US money supply’s Fed-driven explosive growth.

There are no ‘good guys’ in the GME saga. The small traders who banded together via Reddit to create a massive “short squeeze” in the stock of a company that was on its way to bankruptcy have no right to claim the moral high ground, because they set out to do more damage to an already-broken price discovery process in order to make a ‘quick buck’. The short sellers who were ‘squeezed’ paid a legitimate price for poor risk management. The brokers that without warning imposed restrictions on the trading of GME and in some cases forced their customers out of the stock were simply acting to limit their own exposure, in that stockbrokers can be left ‘holding the bag’ when prices go crazy and traders can’t meet margin calls. And politicians are trying to portray themselves as being supportive of the ‘little guy’ while ignoring the underlying cause.

On a side note, the problem with ‘squeezing the shorts’ in the stock of a company with very little underlying value is that if the squeeze is successful then there will be almost no buyers on the way back down. As a result, successful short squeezes are often followed by spectacular price collapses.

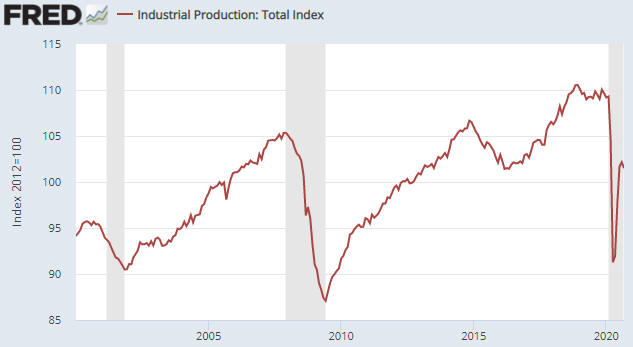

The underlying cause of the crazy price action is the explosive money-supply growth engineered by the Fed. This record-breaking expansion of the money supply hasn’t led to rapid rises in official measures of “price inflation” YET, but its effects are plain to see. One of the most obvious effects at the moment is the rampant speculation in parts of the stock and commodity markets.

The participants in each bubble believe that there are some fundamental considerations that make their bubble special, meaning that their bubble is believed to be not actually a bubble but a reasonable assessment of future prospects. For example, Tesla bulls believe that Tesla’s market cap makes sense considering the company’s future earnings potential, bitcoin bulls believe that bitcoin’s price rise is justifiable and is nothing compared to what’s coming, and many retail equity traders now believe that the stock market offers them a sure-fire way to make a lot of money very quickly without the need to do any real work.

However, all of the spectacular price rises are part of the same story. All of today’s bubbles are linked to what’s being done to money and they all will burst at around the same time, disabusing ‘investors’ of the notion that their favourite bubble is somehow special.

Recognising that an investment is a bubble isn’t a good reason to bet against the investment. In fact, it’s the opposite. Betting against a bubble is one of the surest ways to lose money quickly.

The goal should be to participate in a bubble while paying very careful attention to managing risk. As long as profits are harvested on a regular basis, a sizable cash reserve is maintained and debt-based leverage is avoided, astute investors/speculators can do well during a bubble without taking excessive risk. They won’t do as well as the true believers, but they won’t give back all of their gains after the inevitable collapse occurs.

Print This Post

Print This Post