[This post is an excerpt from a commentary posted at TSI last month]

Gold mining is — to use technical jargon — a crappy business. It doesn’t have to be, it just works out that way due to irresistible incentives associated with the post-1970 monetary system. We explained why in TSI commentaries and some articles at the TSI Blog (for example, HERE) during 2014-2015.

The explanation revolves around the boom-bust cycle caused by the monetary machinations of the banking establishment (the central bank and the commercial banks). For the economy as a whole, malinvestment occurs during the boom phase of the cycle and the bust phase is when the proverbial chickens come home to roost (the investing mistakes are recognised and a general liquidation occurs). For the gold mining industry, however, the malinvestment occurs during the economy’s bust phase, because the boom for gold mining coincides with the bust for the broad economy.

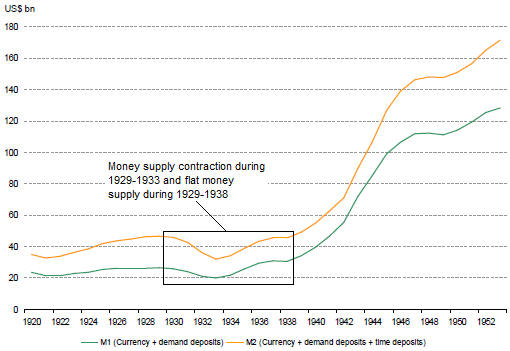

To further explain, rapid monetary inflation distorts relative price signals and in doing so incentivises investments that for a while (usually at least a few years) create the impression that the economy is powering ahead. Eventually, however, many of these investments are revealed for what they are (ill-conceived), with the revelation stemming from rising costs, declining profits or the absence of profit, resource shortages within the economic sectors that ‘boomed’ the most, and rising short-term interest rates due to a scramble for financing to complete projects and/or deal with cash flow problems.

After it starts to become clear that many of the boom-time investments were based on unrealistic expectations, a general drive to become more liquid gets underway. Many people sell whatever they can in an effort to pay expenses and service debts, thus kicking off an economic bust (recession or depression).

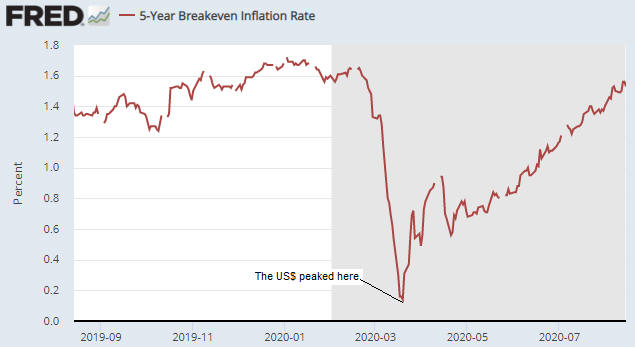

For the average person, becoming more ‘liquid’ usually involves obtaining more cash. However, corporations and high-net-worth individuals often prefer other forms of ‘liquidity’, including Treasury Bills and gold. That, in essence, is why the demand for gold tends to rise during the bust phase of the economy-wide boom-bust cycle.

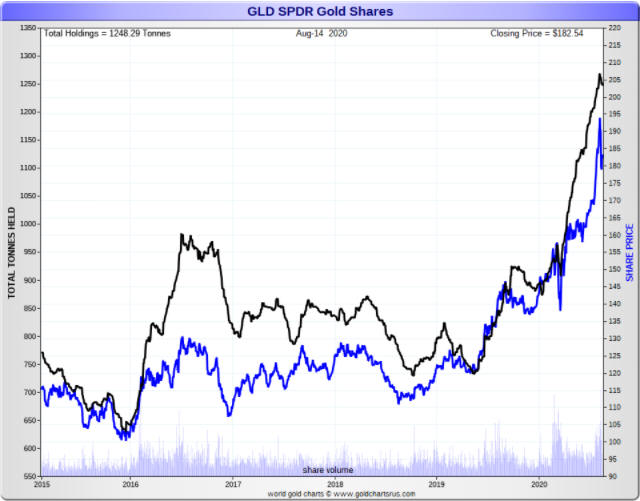

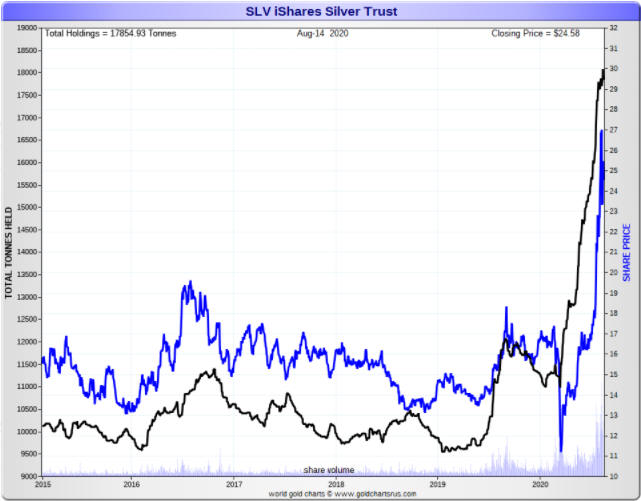

The rising demand for gold pushes up gold’s price relative to the prices of most other assets and commodities, which elevates the general interest in gold mining. Eventually there will be a flood of money towards the gold mining industry that boosts valuations and that the managers of gold mining companies will use for something. That something will be project developments or acquisitions.

Regardless of how high market valuations move or how costly new mine developments become, gold-mining company managers will never say: “We don’t want your money because there currently are no acquisitions or new projects that make economic sense.” Instead, they will take the money and put it to work, based on the assumption that current price trends can be extrapolated into the distant future. The result invariably will be an artificial boom in the gold mining industry characterised by a cluster of high-cost investments that eventually get revealed as ill-conceived. Massive write-offs and an industry-wide retrenchment will ensue as surely as night follows day, thus obliterating the wealth created by the industry during the boom.

Gold itself is not made less valuable by the monetary-inflation-caused inefficiencies and widespread wastage that periodically beset the gold-mining industry. That’s why the gold mining sector, as represented on the following weekly chart by the Barrons Gold Mining Index prior to 1995 and the HUI thereafter, has been in a downward trend relative to gold bullion since 1968. That’s right — gold mining stocks, as a group, have been trending downwards relative to gold for more than 50 years!

The trend illustrated by the above chart is a function of the current monetary system and won’t end before the current system is replaced. The trend could end within the next ten years, but it didn’t end in 2020 and almost certainly won’t end in 2021 or 2022. An implication is that if you want to make a long-term investment in gold, then buy gold. Gold mining stocks are for trading.

Print This Post

Print This Post