This post is an excerpt from a recent TSI commentary.

Every central bank in the world, including the US Federal Reserve, now wants a weaker US$, which proves that central banks can be overwhelmed by market forces even when they are united in their goals.

Central banks outside the US want a weaker US$ due to the long-term consequences of the actions that they themselves took many years ago to strengthen the US$. To put it another way, they now want to strengthen their own currencies against the US$ because their economies are suffering from the inevitable ill-effects of the currency-depreciation policies implemented at an earlier time. As discussed in the past, currency depreciation/devaluation is always counter-productive because it “engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and it does so in a manner that not one man in a million will be able to diagnose.” It is still a very popular policy, though, because at a superficial level — the level at which most economists and all central bankers operate — it seems practical.

Unfortunately for the central banks that are now trying to prop-up their currencies relative to the US$, a central bank’s ability to weaken its currency is much greater than its ability to bring about currency strength. The reason is that weakening a currency can usually be achieved by increasing its supply, and if there is one thing that central banks are good at it’s creating money out of nothing. Actually, creating money out of nothing, and, in the process, engaging all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, is the ONLY thing they are good at.

The problem they are now facing is that once confidence in the currency has been lost, bringing about currency strength or at least a semblance of stability will generally require either a very long period of politically-unpopular monetary prudence or a deflationary depression. There is no quick-and-easy way to obtain the desired result.

The crux of the matter is that there is very little that central banks outside the US can now do in the short-term to stop the US$ from rising. The best they can do is to NOT inflate. Other than that, they should simply avoid the temptation to ‘do something’ and instead just wait for the current trends to exhaust themselves.

The US central bank also wants a weaker US$. This is because the senior members of the Fed operate at the same superficial level as their counterparts throughout the world. They see the direct, short-term positives that a weaker currency would bring to some parts of the economy, but are incapable of seeing the broader, longer-term and indirect negatives.

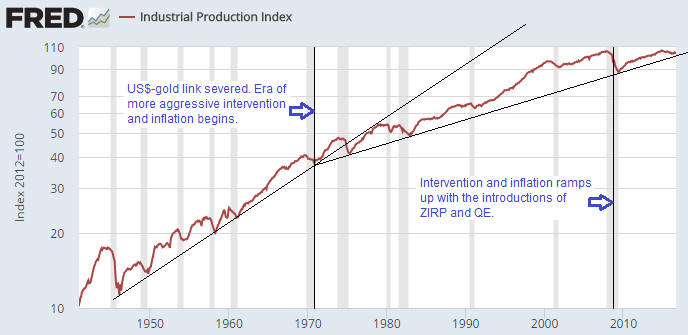

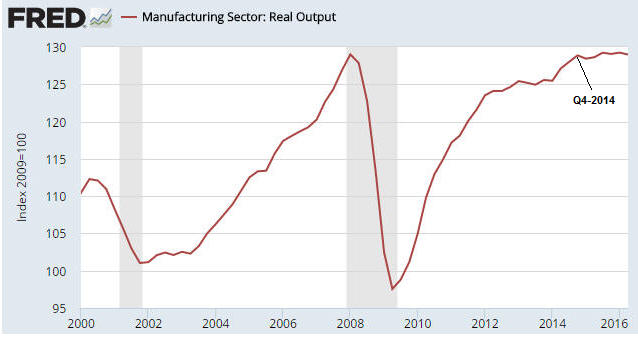

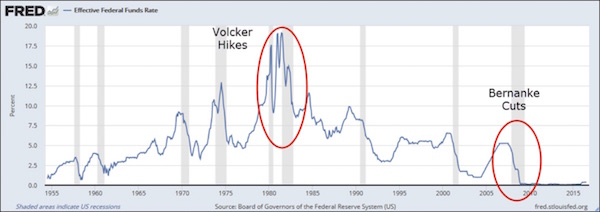

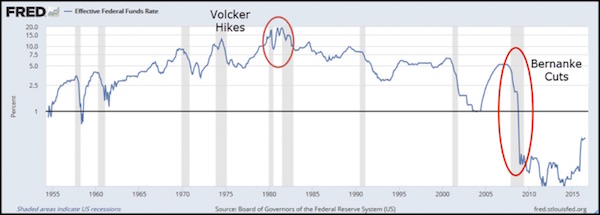

The difference is that the Fed actually has the power to create short-term weakness in the US$. It could, for example, surprise the world by not hiking its targeted interest rate in December. That would knock the Dollar Index down by at least a couple of points. To build on the decline it could then start emphasising the sluggishness of US industrial production and dropping hints that another QE program is coming.

Doing so would, however, be a reckless course of action even by Keynesian standards. The US dollar’s upward trend would be over, but at the cost of a total loss of credibility on the part of the Fed and breathtaking instability in the financial markets.

Once lost, confidence is difficult for a central bank to regain. The Fed is therefore now backed into a corner where for the sake of appearances it will have to take small steps in the direction of tighter monetary policy, even though it would prefer a weaker US$.

Print This Post

Print This Post