There’s a lot right with John Hathaway’s recent article titled “An ‘Acute Shortage’ in Gold Can Boost Prices“. There’s also a lot wrong with it, beginning with the title. There is not now, there has never been and there never will be a shortage of gold*, the reason being that gold is not ‘consumed’ like other commodities. However, my main bone of contention isn’t with the fatally-flawed argument that a gold shortage is looming.

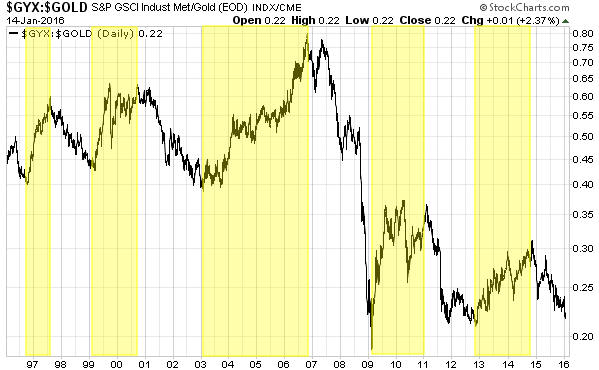

The main problem I have with Hathaway’s article is that it repeats the nonsensical story that the gold price has been forced downward over the past few years to an artificially-low level by the relentless selling of “paper gold”. Like many gold bulls, Hathaway apparently hasn’t noticed that a major commodity bear market has unfolded and that the gold price has held up incredibly well. So well, in fact, that relative to the Goldman Sachs Spot Commodity Index (GNX) the gold price is at an all-time high and about 30% higher than it was at its 2011 peak.

Rather than imagining a grand price suppression scheme involving unlimited quantities of “paper gold” to explain why gold isn’t more expensive, how about trying to explain why gold is now more expensive relative to other commodities than it has ever been.

Considering only US economic and monetary fundamentals, the gold price is now a lot higher than it probably should be relative to the general level of commodity prices. I think that the strength can be explained by the precarious global economic and monetary situations, but the point is that a knowledgeable and unbiased observer of the markets shouldn’t be scratching his/her head or feeling the need to get creative when coming up with justifications for gold’s current US$ price.

Hathaway actually knows the real reason for gold’s downward trend in US$ terms, because at one point in the article he writes: “The negative investment thesis [for gold] seems to rest upon confidence that central bankers, and the Federal Reserve in particular, will steer a course away from radical monetary experimentation that will return to a normal structure of interest rates and robust economic growth.” Yes, that’s it in a nutshell.

Gold’s perceived value is the reciprocal of confidence in the central bank and the economy. Although some of us strongly believe that the confidence was and is misplaced, it’s a fact that confidence in the Fed and the US economy has generally been at a high level over the past few years.

*Note: If it could be validly argued that a genuine gold shortage (as opposed to a temporary shortage of gold in a particular manufactured form) was likely or even just a realistic possibility, then gold would no longer be suitable for use as money. Fortunately, it cannot be validly argued.

Print This Post

Print This Post