[This blog post is an excerpt from a commentary published at TSI last week]

Monetary inflation is the driver of the economic boom-bust cycle, with booms being set in motion by rapid monetary inflation and busts getting underway after the rate of new money creation drops below a critical level and/or it becomes impossible to complete projects due to resource shortages. The following chart shows that the US monetary inflation rate (the year-over-year growth rate of US True Money Supply) extended its decline in September-2022 and is now below 4%, down from a peak of almost 40% early last year.

Due to the economic damage done over multiple cycles by the manipulations of the central bank, the current US economic bust began at a higher rate of monetary inflation than previous busts. In addition, most things related to the current boom-to-bust transition have happened within a compressed timeframe.

In previous cycles over the past three decades, a decline in the monetary inflation rate to below 6% kicked off a sequence lasting 1-2 years encompassing an inversion of the yield curve, a substantial widening of credit spreads (the start of the credit-spreads widening trend combined with the start of an upward trend in the gold/commodity ratio marks the start of the bust phase) and a reversal of the yield curve from flattening/inverting to steepening — PRIOR to the start of an economic recession. This time around, however, all of the above except a steepening of the yield curve occurred within 7 months of a decline in the monetary inflation rate to below 8%.

There is yet to be a reversal in the yield curve from flattening/inverting to steepening, but that’s because this time around the Fed is continuing to tighten monetary conditions aggressively into the teeth of an economic recession. This is similar to what happened in 1973-1974.

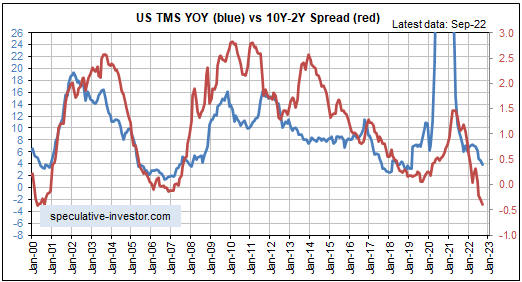

To further explain the above comment, the monetary inflation rate (the blue line on the following monthly chart) drives the yield curve (the red line on the chart). Of particular relevance to this discussion, an inversion of the yield curve (the red line dropping below zero) is an EFFECT of a large decline in the monetary inflation rate, and in general a trend reversal in the yield curve from flattening/inverting to steepening requires an upward trend reversal in the monetary inflation rate.

With the downward trend in the US monetary inflation rate unlikely to end any sooner than the first quarter of next year, a trend reversal in the yield curve (to steepening) is probably still at least several months away. In the meantime, it’s reasonable to expect that the curve will move even further into inverted territory.

As mentioned in the 3rd October Weekly Update, if the Fed sticks with its current balance-sheet reduction plan for only a few more months then by February of next year the year-over-year rate of US money supply growth probably will turn negative, that is, the US will be experiencing monetary deflation. If this happens then the prices of most assets will go much lower than they are today.

As also previously mentioned, economic and stock market weakness eventually will put irresistible pressure on the Fed to commence a new monetary easing campaign, but there is nothing to be gained by trying to guess when that will be. This is because the initial attempts to ‘stimulate’ almost certainly won’t be sufficient to ignite a new boom, and because the stock market usually doesn’t bottom until well after the monetary inflation trend has reversed upward. At the moment we are a long way from such a reversal.