[This blog post is an excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

The 4-8 year period beginning in February of this year potentially will contain three or more official recessions and come to be referred to as the Depression of the 2020s. If so, unlike the Depression of the 1930s the Depression of the 2020s will be inflationary.

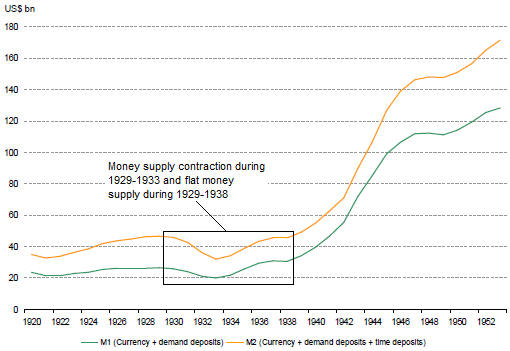

The Depression of the 1930s was deflationary in every sense of the word, but the primary cause of the deflation was the performance of the money supply. We don’t have the data to calculate True Money Supply (TMS) during the 1930s, but we have the following chart showing what happened to the M1 and M2 monetary aggregates from 1920 to 1953. The chart shows that there was a substantial contraction in the US money supply during 1929-1933 and that the money supply was no higher in 1938 than it had been at the start of the decade.

Clearly, the money-supply situation today could not be more different from the money-supply situation during the early-1930s*.

One reason for the difference is that during the 1930s the Fed was restricted by the Gold Standard. The Gold Standard was diluted in 1933, but throughout the 1930s the US$ was tethered to gold.

The final official link between the US$ and gold was removed in 1971. This made it possible for the Fed to do a lot more, but as far as we can tell the Fed actually didn’t do a lot more in the 1990s than it did in the 1960s. It has been just the past 20 years, and especially the past 12 years, that the Fed has transmogrified from an institution that meddles with overnight interest rates and bank reserves to a central planning agency that attempts to micro-manage the financial markets and the economy. After history’s greatest-ever mission creep, it now seems that there is nothing associated with the financial markets and the economy that is outside the Fed’s purview.

In parallel with the expansion of the Fed’s powers and mission there emerged the idea that for a healthy economy the currency must lose purchasing power at the rate of around 2% per year. This idea has come to dominate the thinking of central bankers, but it has never been justified using logic and sound economic premises. Instead, when asked why the currency must depreciate by 2% per year, a central banker will say something along the lines of: “If the inflation rate drops well below 2% then it becomes more difficult for us to implement monetary policy.”

As an aside, because of the way the Fed measures “inflation”, for the Fed to achieve its 2% “inflation” target the average American’s cost of living probably has to increase by at least 5% per year.

Due to the central-banking world’s unshakeable belief that money must continually lose purchasing power and the current authority of the central bank to do whatever it takes to achieve its far-reaching goals, the greater the perceived threat of deflation the more monetary inflation there will be. We saw an example of this during 2001-2002 and again during 2008-2009, but 2020 has been the best example yet. The quantity of US dollars created since the start of this year is greater than the entire US money supply in 2002.

It actually would be positive if deflation were the high-probability outcome that many analysts/commentators claim it is, because deflation is relatively easy to prepare for and because 1-2 years of severe deflation would set the stage for strong long-term growth. However, one of today’s dominant driving forces is the avoidance of short-term pain regardless of long-term cost, so there will be nothing but inflation until inflation is perceived to be the source of the greatest short-term pain. This doesn’t mean that a depression will be sidestepped or even postponed. What it means is that the next depression — which may have already begun — will be the inflationary kind.

*US True Money Supply (TMS) has expanded by 35% over the past 12 months.

Print This Post

Print This Post