[This blog post is an excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

Moore’s Law, which is based on a comment by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in the 1960s, states that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years. In effect, it states that the computer industry’s efficiency doubles every two years. Moore’s Law worked well in the semiconductor/computer industry for a few decades, but that was due to a set of circumstances that existed in that particular industry over a certain time rather than the general applicability of the ‘law’. The ‘law’ no longer works in the computer industry and can’t be applied in a useful way to technology in general. Wright’s Law, on the other hand, is more useful when it comes to explaining and predicting the effects of technology-driven improvements in efficiency. Wright’s Law pre-dates Moore’s Law by about 30 years (it was postulated by Theodore Wright in 1936) and states that for every cumulative doubling of units produced, costs will fall by a constant percentage.

The reason that Wright’s Law works better than Moore’s Law (Wright’s Law can be applied to all industries and has even been more accurate than Moore’s Law in the computer industry) is that it focuses on cost as a function of units produced rather than time. The beauty of Wright’s Law is that once an industry has been around for long enough to determine the relationship between the increase in units produced and the reduction in unit cost, accurate predictions can be made regarding what’s likely to happen over years and even decades into the future. The limitation is that a certain amount of history is required to establish the percentage reduction in cost that accompanies a certain increase in the production rate.

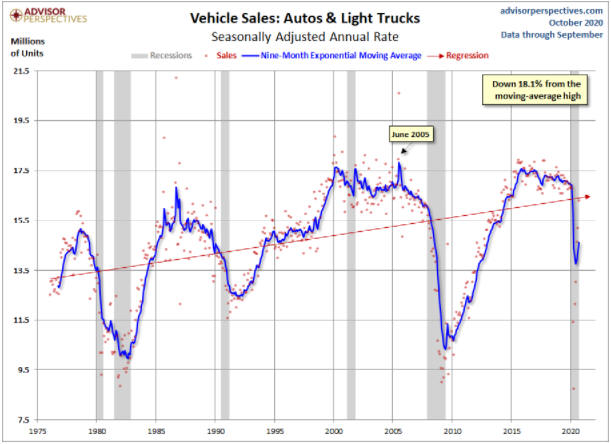

It should be possible to apply Wright’s Law to any growing industry. Of particular relevance to this discussion it should apply in the Electric Vehicle (EV) industry over the next several years, whereas it should no longer apply in the Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicle industry. It probably won’t apply to ICE vehicle manufacturing in the future because the production rate of such vehicles appears to have peaked on a long-term basis. As evidence we cite the following chart of light vehicle sales in the US since the mid-1970s. This chart shows that the 9-month moving average of annualised light vehicle sales in the US peaked in 2005 and is lower today than it was in the mid-1980s.

Chart Source: advisorperspectives.com

Total light vehicle sales have peaked in many parts of the world, but EV sales are experiencing exponential growth. This implies that vehicle components that are specific to EVs, most notably batteries and electric motors, are going to get cheaper and cheaper. This will not only improve the economics of EVs in absolute terms, it will improve the economics of EVs relative to ICE vehicles.

Taking into account the life-of-vehicle cost, that is, the cost to buy plus the on-going costs to run and maintain, EVs already are competitive with ICE vehicles without the requirement for government subsidies, but within the next three years the economic benefits of choosing an EV over an ICE vehicle will become irresistible to most new car buyers in developed countries. This will happen with or without government incentives to buy EVs. It will happen because of Wright’s Law.

An implication is that current car and truck manufacturers that can’t figure out how to make EVs that consumers want to buy will disappear. Another implication will be a large increase in demand for the commodities that go into vehicle components that are specific to EVs. The commodities that spring to mind are the rare earth metals Neodymium and Praseodymium (NdPr), which are used in electric motors, and lithium, nickel and manganese, which are used in EV batteries.

Keep in mind, though, that the size of the EV market is limited by an overall light vehicle market that probably will be smaller in 15 years than it is today, because the combination of self-driving and ride-sharing will bring the age of personal car ownership to an end.

Wright’s Law naturally results in huge benefits for the average person, but central bankers think that they have to fight it. Even though prices naturally fall over time due to economic progress, central bankers believe that prices should rise, not fall. Therefore, they deliberately try to counteract the efficiency improvements that people in the marketplace are constantly trying to create. They do so by pumping new money into the economy or by encouraging commercial banks to lend new money into existence.

In general, the fast-growing industries that are focused on technological advancement are still able to reduce prices in the face of the central bank’s price-distorting efforts. This leads to the price rises being concentrated in industries where, due to government regulations or the nature of the industry, there is less scope for technology to drive prices downward. For example, Amazon.com was able to drive prices downward in the face of the Fed’s “inflationary” efforts, but most of its brick-and-mortar competitors were not. Other examples are the education and healthcare industries, where regulations and direct government ownership get in the way.

It’s hard to overstate the stupidity of a central bank strategy that is designed to make the economy less efficient. Currently we have the absurd situation in which the faster the rate of technological progress, the more that central banks do to create “inflation” and thus offset the benefits of this progress. They aren’t doing this because they are malicious, they are doing it because they are trapped within an ideological framework that prevents them from understanding the way the world works.

Print This Post

Print This Post