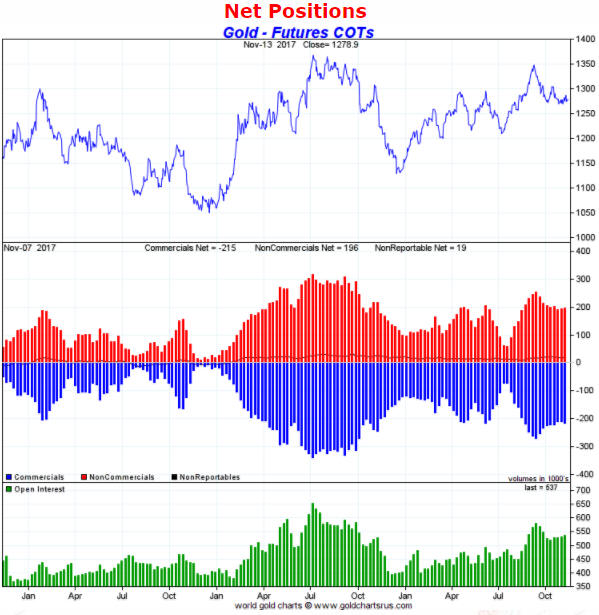

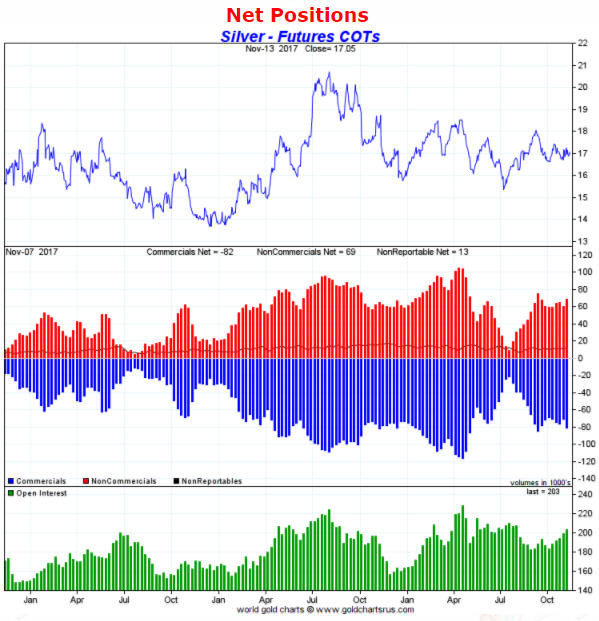

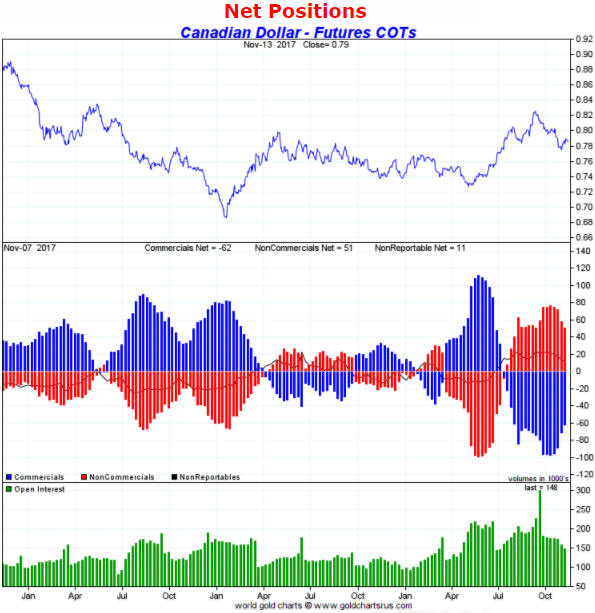

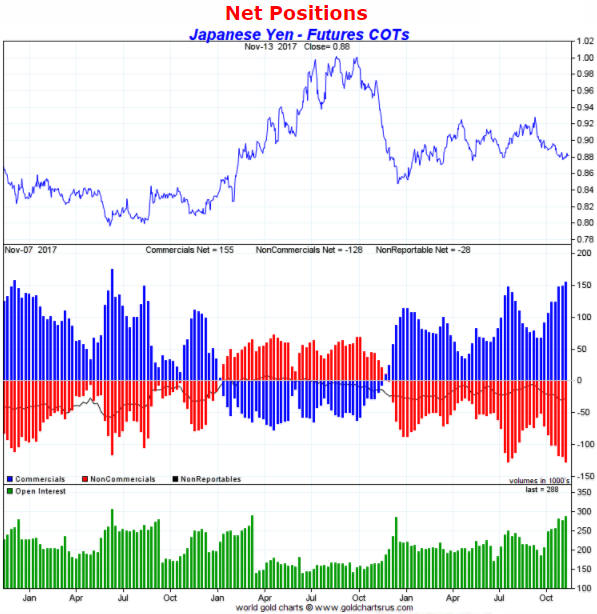

A blog post titled “Sentiment Synopsis” posted two weeks ago contained some explanatory remarks about the Commitments of Traders (COT) reports and briefly discussed the sentiment situations for gold, silver, the Canadian dollar and the Yen using the COT data as the indicators of market sentiment. In this post I’ll do the same for the euro, the Swiss franc and oil, again with the help of charts from Gold Charts ‘R’ Us.

As noted in the earlier post, what I refer to as the total speculative net position takes into account the net positions of large speculators (non-commercials) and small traders (the ‘non-reportables’) and is the inverse of the commercial net position. The blue bars in the middle sections of the charts that follow indicate the commercial net position, so the inverse of each of these bars is considered to be the total speculative net position.

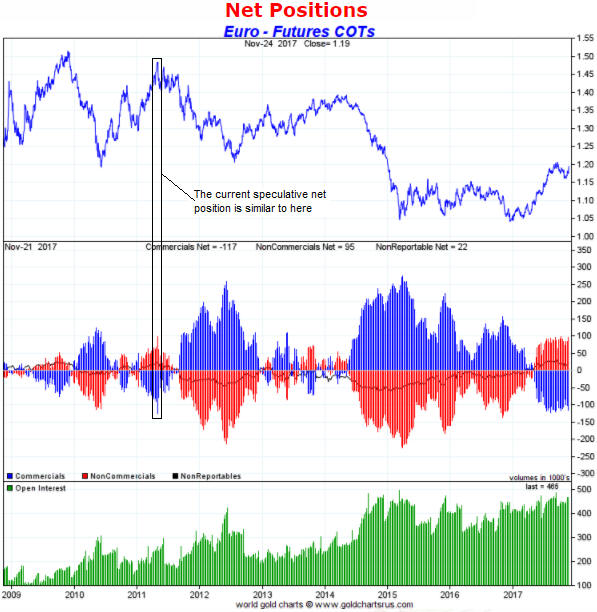

Let’s begin with the euro.

For the past few months the net speculative long position in euro futures has hovered near an all-time high. In fact, the only time that speculators in currency futures, as a group, have ever bet more heavily on a rise in the euro was in 2011 when the euro/US$ exchange rate was peaking in the high-1.40s. Consequently, it could be argued that sentiment is more conducive to euro weakness than euro strength in the short-term.

There is, however, a caveat, which is that if speculators were to become as bullish on the euro as they were bearish in Q2-2012 or Q1-2015 then the speculative net-long position in euro futures will become much larger than at any time in the past. The current COT situation should therefore be viewed as a short-term warning of euro weakness, but not a reason to place a substantial bearish bet.

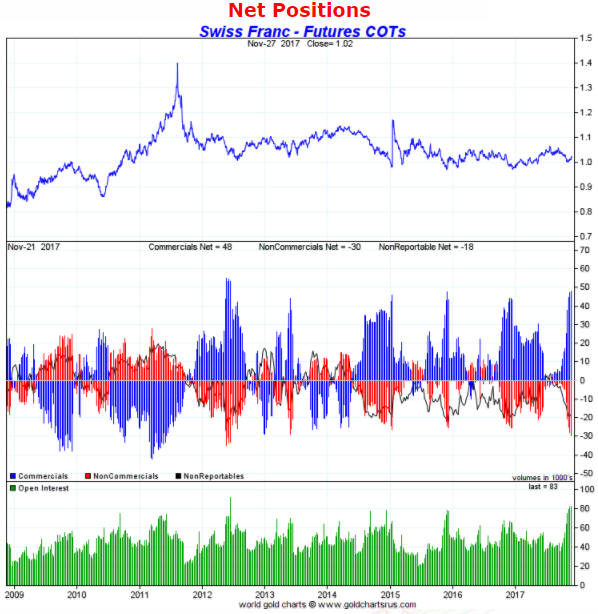

Turning to the following Swiss franc (SF) chart we see the opposite situation. Whereas the COT report indicates that speculators in the futures market are almost as bullish on the euro as they have ever been, it also indicates that the same speculators are almost as bearish on the SF as they have ever been. In particular, it was only for a brief period in 2012 that currency speculators, as a group, were more short (that is, more bearish) on the SF than they are right now. It looks very much like speculators in currency futures have been buying the euro and selling the SF as a pair trade, undoubtedly to take advantage of the downward trend in the SF/euro exchange rate that got underway in April.

I view the current COT situation as a reason to be short-to-intermediate-term bullish on the SF relative to both the US$ and the euro.

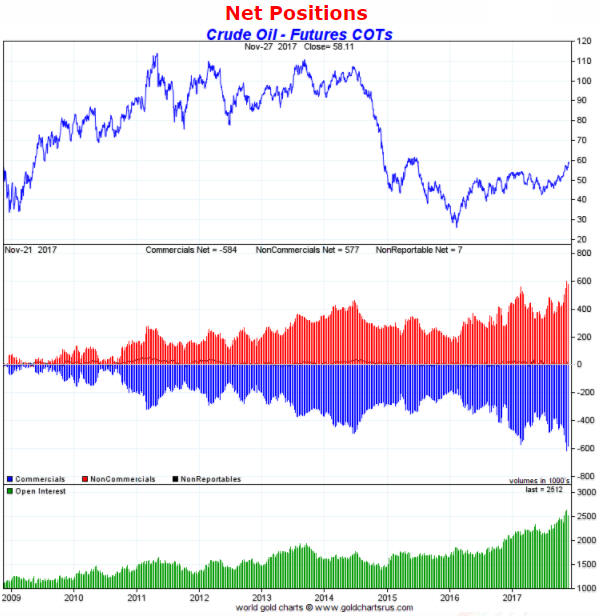

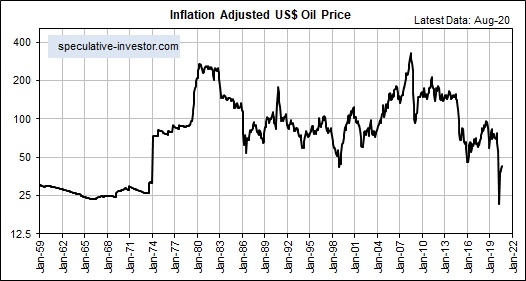

Last but not least, below is a chart showing the COT situation for US (West Texas Intermediate) crude oil futures. The chart tells us that the net speculative long position in oil futures made an all-time high two weeks ago and remains close to its high.

Based on considerations other than sentiment I expect the oil price to trade well into the $60s during the first half of next year, but oil’s COT situation is a short-term danger sign. In the absence of a steady stream of bullish news the oil price is likely to trade at least 10% below its current price within the next two months. I hasten to point out, however, that the risk/reward does not suggest that oil should be shorted.

Print This Post

Print This Post