Page 4 in Hoisington Investment Management’s latest Quarterly Review and Outlook contains a discussion about the falling productivity of debt problem. According to Hoisington and many other analysts, the problem is encapsulated by the falling trend in the amount of GDP generated by each additional dollar of debt, or, looking from a different angle, by the rising trend in the amount of additional debt required to generate an additional unit of GDP. However, there are some serious flaws in the “Productivity of Debt” concept.

There are three big problems with the whole “it takes X$ of debt to generate Y$ of GDP” concept, the first being that GDP is not a good indicator of the economy’s size or progress.

For one thing, GDP is a measure of spending, not a measure of wealth creation. It’s possible, for example, for GDP to grow rapidly during a period when wealth is being destroyed on a grand scale. This could happen during war-time and it could also happen as the result of massive government spending on make-work projects. It’s also possible for GDP to grow slowly at a time when the rate of economic progress is high. This can happen because GDP is dominated by consumption. It omits all business-to-business expenditure and misses a lot of value-adding investment.

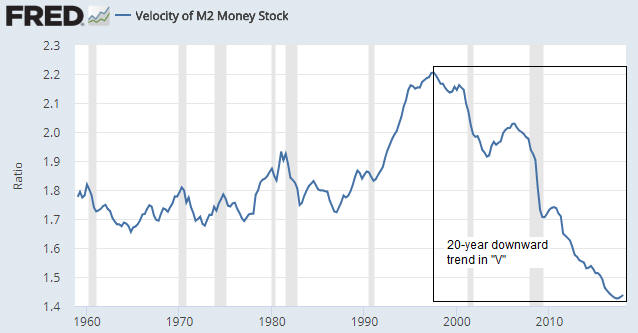

For another thing, GDP is strongly influenced by changes in the money supply. Of particular concern, even though an increase in the money supply cannot possibly cause a sustainable increase in economy-wide wealth, it will usually boost GDP.

Therefore, comparing anything with GDP is problematic.

The second flaw in the “it takes X$ of debt to generate Y$ of GDP” concept is that it involves comparing a flow (annual GDP) to a stock (the cumulative total of debt). There are times when it can make sense to compare a stock to a flow, but care must be taken when doing so. I’ll use a hypothetical example to show one of the pitfalls.

Assume that over the course of a year an economy goes from a GDP of $10T and a total debt of $50T to a GDP of $10.4T and a total debt of $52T. This could prompt the claim that it took $2T of additional debt to boost GDP by $0.4T, or that $5 of additional debt was needed for every $1 of additional GDP. However, it could also be said that a 4% increase in debt was associated with a 4% increase in GDP. The second way of expressing the same change seems far less worrisome.

In any case, the above two flaws in the typical productivity-of-debt analysis pale in comparison with the third flaw, which is that the entire concept of debt productivity is meaningless. The fact is that debt doesn’t cause economic growth and ‘excessive debt’ (whatever that is) doesn’t inhibit economic growth.

An economy can grow with or without an increase in debt, because per-capita economic growth is caused by savings and capital investment. An increase in debt can accelerate the pace of real growth by acting as a means by which savings are channeled to where they can be invested to the best effect, but the transfer of savings can also occur via the exchange of money for equity. For example, most exploration-stage mining companies and most technology start-ups are equity-financed not debt-financed. There is, of course, debt that is used to finance consumption rather than investment, but that type of debt can’t grow the economy over the long term because it necessarily involves a present-future trade-off — more spending in the present leads to less spending in the future.

The central problem is unsound money, not excessive debt. More specifically, the problem is that when banks make loans they create money out of nothing. It’s this creation of money out of nothing and the subsequent exchange of nothing for something, not the build-up of debt, that leads to reduced productivity. If all debt involved the lending/borrowing of real savings then no amount of debt could ever make the overall economy less efficient. Of course, if all debt involved the lending/borrowing of real savings then the total amount of debt would be a small fraction of what it is today.

Print This Post

Print This Post