Here is an excerpt from a commentary posted at TSI on 6th August.

The monthly US employment reports have no relevance except for their influence on the Fed and market expectations regarding future Fed actions. The moderately strong employment data reported last Friday, for example, provides no information about the current or likely future performance of the US economy, but was noteworthy because it led to a slight increase in the expected level of the Fed Funds Rate (FFR).

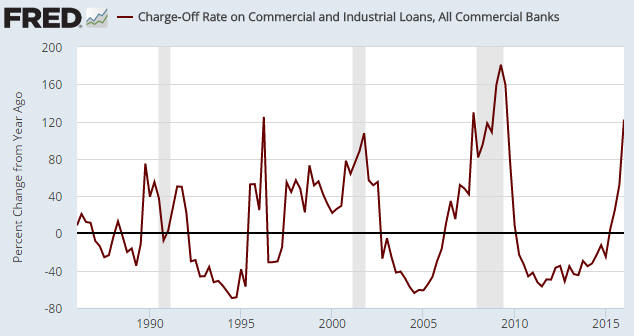

The change in the expected level of the FFR in response to Friday’s employment news is illustrated by the following daily chart. The last bar on the chart shows a fall of 0.09 in the price of the January-2018 Fed Funds Futures (FFF) contract, which means that the expected level of the FFR in January-2018 rose by 0.09 (9 basis points) last Friday.

Now, under more normal circumstances a 0.09% change in the expected level of the FFR in 17 months’ time would not have a significant effect on the gold market, but these aren’t normal circumstances. These are circumstances in which the actions and expected future actions of central banks are dominating all other considerations. Consequently, just as a minor decrease in the expected FFR during the final week of July and the first two trading days of August propelled the gold price from around $1310 to the $1370s, a minor increase in the expected FFR on Friday predictably had the opposite effect.

Does this mean that if the expected FFR builds on Friday’s gain over the days/weeks ahead then the gold price will probably trend downward over the same period? Yes, that’s exactly what it means. It also means that if something happens in the world to cause the expected FFR to move below the lows of the past few weeks then the gold price will probably move to a new high for the year.

Print This Post

Print This Post