Do gold mining stocks, as represented by the Barrons Gold Mining Index (BGMI) or the XAU or the HUI, lead gold bullion at significant turning points? According to many analysts the answer is a resounding “yes”. However, according to the historical record the answer is “sometimes, but not consistently”. I’ll go with the historical record.

There are plenty of examples of gold mining stocks leading the bullion price at a turning point from down to up or up to down, but there are at least as many examples of gold mining stocks lagging the bullion at a turning point. The most blatant example of the latter occurred in 1980. It is well known that gold bullion reached a long-term price top in January-1980, but it is less well known that gold mining stocks, as represented on the following weekly chart by the BGMI, experienced a huge rally after the major high in the gold price and didn’t reach a long-term peak of their own until September-1980.

Another example of gold bullion leading the gold-mining sector at a meaningful turning point occurred during the mid-1980s. First, gold bullion reached a multi-year bottom in February-1985, but it wasn’t until July-1986 that the XAU reached a similar bottom. Second, the XAU commenced an intermediate-term rally in late-July of 1986, but as noted on the following daily chart the associated bottom in the gold price occurred about 6 weeks earlier.

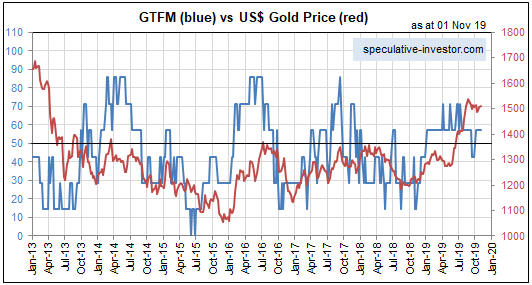

Here are examples of the same lead-lag relationship from the more recent past:

1) Gold bottomed on a long-term basis in early-December of 2015, but the equivalent low for the HUI didn’t occur until mid-January of 2016. Gold then reached an intermediate-term top in July-2016, but the associated top for the HUI wasn’t put in place until about a month later. In other words, the gold-mining sector lagged the bullion market at both the start and the end of the 2016 intermediate-term rally.

2) Gold made an intermediate-term bottom in August-2018, whereas the HUI waited until September-2018 to make an intermediate-term bottom of its own. Then, in May of 2019 the HUI made a sequence of lower correction lows while gold bullion remained above the low it made at the beginning of the month.

In my experience, rather than labour under the unreliable assumption that gold stocks lead the bullion at turning points, any divergence or non-confirmation between gold stocks and gold bullion should be viewed as potentially bullish after prices have become stretched to the downside and potentially bearish after prices have become stretched to the upside. For example, after prices have been trending downward for several months, a new multi-month low in the gold price that isn’t quickly confirmed by the HUI or a new multi-month low in the HUI that isn’t quickly confirmed by the gold price should be viewed as a bullish sign. By the same token, after prices have been trending upward for several months, a new multi-month high in the gold price that isn’t quickly confirmed by the HUI or a new multi-month high in the HUI that isn’t quickly confirmed by the gold price should be viewed as a bearish sign.

To put it more simply, non-confirmations between the gold price and the related mining indices matter, but it doesn’t matter whether the non-confirmations involve relative strength or relative weakness in the mining sector.

Print This Post

Print This Post