Officially, the US has a fractional-reserve banking system (as does almost every other country), meaning that a fraction of deposits are backed by cash reserves held in bank vaults or at the Fed. In reality, the US has a zero-reserve banking system.

I don’t mean that there are no reserves in the banking system, as currently there are huge reserves courtesy of the Fed’s QE programs. What I mean is that there is no relationship between bank reserves and bank lending and that bank reserves do not impose any limit on bank deposits. It has been this way for about 25 years.

To further explain, the most important aspect of a fractional reserve banking system is that a bank can create new deposits by lending out existing deposits up to the point where its total deposits are a predetermined multiple of its reserves. The aforementioned multiple is called the “money multiplier” and the maximum “money multiplier” is the reciprocal of the minimum reserve requirement. For example, in a system where a bank’s reserves are required to be at least 10% of its total deposits, the potential “money multiplier” is 10. In the current US system, however, there is effectively no lower limit on reserves, which means that the so-called “money multiplier” can correctly be thought of as either non-existent or infinite.

Regardless of their deposit levels, US banks are able to reduce their required reserve levels to zero. This is possible for two reasons. First, only demand deposits are subject to reserve requirements. Second, banks employ software that shuffles money between accounts to ensure that they fulfill the regulatory reserve requirement regardless of their actual deposit and reserve levels. For example, you might think you have a demand deposit, but for regulatory purposes what you might actually have is a zero-interest CD.

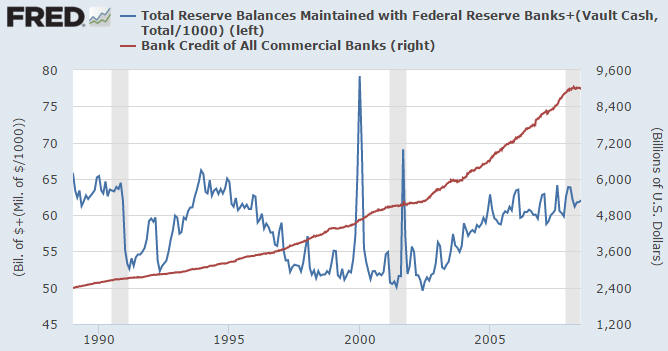

The absence of any relationship between US bank reserve levels and US bank credit is illustrated by the following chart. The chart compares total US bank credit and total bank reserves (vault cash plus reserves held at the Fed) from the beginning of 1989 through to mid-2008 (just prior to the start of the QE programs that swamped the normal relationships). During this period, bank credit shot up from $2,400B to $9,000B while total bank reserves oscillated between $50B and 65B. Notice that the volume of bank reserves was actually a little lower in 2008 with bank credit at $9.0T than in 1989 with bank credit at $2.4T.

An implication, even prior to the QE programs that inundated the banks with reserves, is that the US fractional-reserve banking system will never go into reverse due to a shortage of reserves. In other words, US banks will never contract their balance sheets due to a lack of reserves. Another implication is that having a huge pile of “excess” reserves will never cause banks to expand credit. Instead, regardless of their reserve levels banks will expand or contract credit to the extent that their overall balance sheets can support additional leverage and they can find willing/qualified borrowers.