Print This Post

Print This Post

Print This Post

Print This Post

Gold manipulators should be fired for poor performance

Despite the huge differences between gold and all other commodities, gold is still a commodity and its US$ price is still affected by the overall trend in commodity prices. In particular, a major decline in commodity prices will naturally put downward pressure on the gold price and a major advance in commodity prices will naturally put upward pressure on the gold price. That’s why gold’s performance can be most clearly ‘seen’ by comparing it to the performances of other commodities. When this comparison is done it becomes apparent that gold is now very expensive or at least very highly-priced relative to historical levels.

As evidence I present the following chart of the gold/CRB ratio. This chart shows that relative to the basket of commodities represented by the CRB Index, gold has just made a new multi-decade high.

When I look at the above chart I can’t help but think it’s just as well that gold is being manipulated lower, because just imagine how expensive it would otherwise be.

It won’t surprise me if gold moves even higher relative to commodities in general over the coming month in parallel with an on-going flight from risk. Also, I expect the long-term upward trend in the gold/CRB ratio to continue. Lastly, it’s clear that the operators of the great gold-market price-suppression scheme have been doing a lousy job and deserve to be fired for poor performance.

Print This Post

Print This Post

China’s bubble has burst

When I say that China’s bubble has burst I’m not referring to the recent large decline in the stock market. Although the stock market was the focal point of Chinese speculation during 2006-2007 and during an 8-month period beginning last October, in the grand scheme of things it is no more than a sideshow. Unfortunately, the stock market crash is a minor issue compared to the main problem.

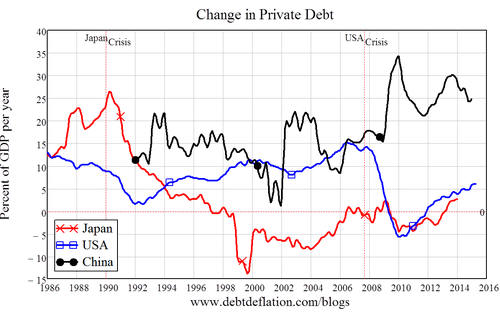

The main problem is that China’s economy is the scene of a credit bubble of historic proportions. That this is indeed the case is evidenced by the following charts from an article posted by Steve Keen last week.

The first chart shows the ratio of private debt to GDP over the past 30 years for the US (the blue line), Japan (the red line) and China (the black line). In particular, the chart shows that China’s current private-debt/GDP is well above the 30-year high for US private-debt/GDP, which suggests that China’s private-debt bubble is bigger than the US bubble that burst in 2007-2008.

The above chart indicates that China’s private-debt bubble isn’t yet as big as the bubble that popped in Japan in the early-1990s, but the next chart shows that the rate of private-debt growth in China over the past several years is far in excess of anything that happened in either Japan or the US in the years leading up to their respective bubble peaks.

There’s no telling how big a credit bubble will become before it bursts, so the fact that China’s economy is host to one of history’s greatest-ever credit bubbles doesn’t mean that the bubble won’t continue to inflate for years to come. However, there are clues that China has transitioned to the long-term bust phase of the monetary-inflation-fueled boom-bust cycle, that is, there are clues that China’s bubble has burst.

Chief among these clues is the large and accelerating flow of money out of China. So-called “capital outflows” from China have been increasing over the past 12 months and according to a recent Telegraph article amounted to $190B over just the past 7 weeks.

Pressure caused by the flow of “capital” out of China led to the small Yuan devaluation that garnered huge media coverage a couple of weeks ago. In an effort to maintain the semblance of stability, if China’s government had been able to delay the inevitable and keep the Yuan propped-up at an artificially-high level for longer, it would have done so. In other words, the devaluation was a tacit admission by China’s government that the pressure caused by capital outflows had become too great to resist.

Once a private-sector credit bubble begins to unwind, the process is irreversible. The standard Keynesian remedy is to replace private debt with public debt, but all this does is add new distortions to the existing distortions.

Print This Post

Print This Post

The meaning of the 6-year low in GLD’s bullion inventory

At the end of the week before last the amount of physical gold held by the SPDR Gold Trust (GLD), the largest gold bullion ETF, fell to its lowest level since September-2008. What does this tell us?

In many TSI commentaries over the years and in a couple of posts at the TSI blog over the past year I’ve explained that changes in GLD’s bullion inventory are not directly related to the gold price. Neither a large rise nor a large fall in the gold price would necessarily require a change in GLD’s inventory, the reason being that as a fund that holds nothing other than gold bullion the net asset value (NAV) of a GLD share will naturally move by the same percentage amount as the gold price.

However, there is an indirect relationship between the gold price and GLD’s bullion inventory. At least, there has been such a relationship in the past. I am referring to the long-term correlation between the gold price and the GLD inventory that stems from changes in sentiment.

As traders in GLD shares become more optimistic about gold’s prospects they sometimes buy aggressively enough to push the market price of GLD above its NAV, which prompts an arbitrage trade by Authorised Participants (APs) involving the issuing of new GLD shares and the addition of physical gold to GLD’s inventory. And as traders in GLD shares become more pessimistic about gold’s prospects they sometimes sell aggressively enough to push the market price of GLD below its net asset value (NAV), prompting an arbitrage trade by APs involving the redemption of GLD shares and the removal of physical gold from GLD’s inventory.

That is, changes in GLD’s market price relative to its NAV create opportunities for arbitrage trades that adjust the supply of GLD shares and the amount of physical bullion held by the fund, thus ensuring that the market price never deviates far from the NAV. This modus operandi is common to all ETFs.

Since traders in GLD shares tend to become more optimistic in reaction to a rising price and less optimistic in reaction to a falling price, the most aggressive buying of GLD shares will tend to occur after the gold price has been trending higher for a while and the most aggressive selling of GLD shares will tend to occur after the gold price has been trending lower for a while. This explains why the following chart shows that the long-term correlation between the gold price and the GLD inventory is strongly positive and why the major downward trend in GLD’s inventory began well after the 2011 peak in the gold price.

The upshot is that the price trend is the cause and the GLD inventory is the effect.

In conclusion, here are three implications of the above:

1) Anyone who claims that the gold price has trended lower over the past few years due to the selling of gold from GLD’s inventory is getting cause and effect mixed up.

2) Anyone who claims that gold is being removed from GLD’s inventory to satisfy demand in Asia (or elsewhere) is either clueless about how ETFs work or is telling untruths to promote an agenda.

3) The early-August decline in GLD’s bullion inventory to a new multi-year low was consistent with the price action. It was evidence that GLD traders were getting increasingly bearish in reaction to lower prices. They loved it at $1600-$1900 and they hated it below $1100.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Everything is obvious with the benefit of hindsight

Almost every major price move in the financial markets looks predictable after it happens. This is called “hindsight bias”, which is defined thusly at Wikipedia:

“Hindsight bias, also known as the knew-it-all-along effect or creeping determinism, is the inclination, after an event has occurred, to see the event as having been predictable, despite there having been little or no objective basis for predicting it.”

Almost everyone suffers from hindsight bias to some degree. Of special relevance to me, many newsletter writers and other commentators on the financial markets are afflicted by it. After the event they are quick to explain how a big price move was totally predictable, but often forget to explain why they didn’t predict it ahead of time or perhaps even predicted the opposite of what happened.

It’s important to recognise hindsight bias when it occurs in the market-related opinions/analyses/ramblings you read and when it occurs in yourself. And with regard to the latter it is important not to beat yourself up or wallow in regret when the future turns out to be different from what you expected. Regardless of how predictable an outcome appears to have been with the benefit of hindsight, you can be sure that prior to it happening there were other realistic possibilities. It’s just that these other possibilities shrank to nothingness when they didn’t happen.

The best way to deal with the fact that nothing is certain without the benefit of hindsight is to simply accept the possibility that the future will not pan-out as you expect and position yourself accordingly. In particular, don’t bet so heavily on a specific outcome that you will be financially devastated if something different happens.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Basic Gold Market Facts

Here are ten basic gold-market realities that are either unknown or ignored by many gold ‘experts’.

1. Supply always equals demand, with the price changing to maintain the equivalence. In this respect the gold market is no different from any other market that clears, but it’s incredible how often comments like “demand is increasing relative to supply” appear in gold-related articles.

2. The supply of gold is the total aboveground gold inventory, which is currently somewhere in the 150K-200K tonne range. Mining’s contribution is to increase the aboveground inventory by about 1.5% each year. An implication is that there should never be a shortage of gold.

3. Although supply always equals demand, the price of gold moves due to sellers being more motivated than buyers or the other way around. Moreover, the change in price is the only reliable indicator of whether the demand side (the buyers) or the supply side (the sellers) have the greater urgency. An implication is that if the price declines over a period then we know, with 100% certainty, that during this period sellers were more motivated (had greater urgency) than buyers.

4. No useful information about past or future price movements can be obtained by counting-up the amount of gold bought/sold in different parts of the gold market or different parts of the world. An implication is that the supply/demand analyses put out by GFMS and used by the World Gold Council are generally useless in terms of explaining past price moves and assessing future price prospects.

5. Demand for physical gold cannot be satisfied by “paper gold”.

6. Prices in the physical and paper (futures) markets are linked by arbitrage trading. For example, if speculative selling in the futures market drives the futures price down relative to the physical (or cash) price by a sufficient amount then arbitrage traders will profit by selling the physical and buying the futures, and if speculative buying in the futures market drives the futures price up relative to the physical (or cash) price by a sufficient amount then arbitrage traders will profit by selling the futures and buying the physical.

7. The change in the spread between the cash price and the futures price is the only reliable indicator of whether a price change was driven by the cash/physical market or the paper/futures market.

8. In a world where US$ interest rates are much lower than usual, the difference between the price of gold in the cash market and the price of gold for future delivery will usually be much smaller than usual. In particular, when the T-Bill yield is close to zero, as is the case today, there will typically be very little difference between the spot price of gold and the price for delivery in a few months. An implication is that in the current financial environment the occasional drift by gold into “backwardation” (the futures price lower than the spot price) will not be anywhere near as significant as it would be under more normal interest-rate conditions.

9. Major trends in the US$ gold price are determined by changes in the general level of confidence in the Fed and the US economy. An implication is that major price trends have nothing to do with changes in jewellery demand, mine supply, scrap supply, central bank buying/selling, and the amounts of gold being imported by India and China.

10. The amount of gold in COMEX warehouses and the inventories of gold ETFs follow the major price trend, meaning that changes in these high-profile inventories are effects, not causes, of changes in the gold price.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Facts, Opinions, and Risk Management

Commentators on the financial markets often make statements like “it’s a bull market” and “the trend is up” as if these were indisputable facts, but such statements are always opinions.

A statement of fact could reasonably be phrased along the lines of “the market was in an upward trend between date X and date Y”, because if a sequence of rising lows and rising highs occurred between two dates then the trend was, by definition, up during that period. However, it is impossible to know the direction of a market’s current price trend with absolute certainty, let alone the direction of its future price trend. The reason is that even if a market has just made a new high/low there will be some chance that this will turn out to be the ultimate high/low.

For example, it’s a fact that gold was in a bear market in US$ terms from its peak in September of 2011 through to 24th July 2015 (when it hit a 4-year low of $1072), but it is a matter of opinion as to whether gold is now in a bear market. The bear market could obviously still be in progress, but there is also a possibility that it ended on 24th July 2015. At the time of writing, nobody knows for sure.

Some market participants and commentators will draw a line on a chart and then make a statement such as “I will consider the trend to be up (or down) unless the market proves otherwise by moving below (or above) my line”. Fine, but there’s a big difference between claiming to know the direction of the price trend and working under the assumption that the trend is in a particular direction unless/until proven otherwise by some predetermined event. The valley of shattered financial dreams is littered with traders who were determined to stay ‘long’ or ‘short’ because they thought they KNEW the direction of the price trend.

The impossibility of knowing whether a bull/bear market or an up/down trend is going to continue, or even whether the market is currently in bull or bear mode, makes risk management essential. Someone who knew the future would never have to bother with risk management; they could, instead, risk everything on a particular outcome because for them it wouldn’t be a risk at all. But ordinary mortals always face a degree of uncertainty when making investment decisions and, as a result, always need to face the reality that these decisions could prove to be wrong. Be wary, then, of advisors who claim that there is only one possible direction for the future price of an investment.

But while unwillingness to acknowledge the possibility of being wrong is a defect in the approach of some investors, other investors suffer from the opposite problem in that they have a hard time maintaining a bullish or bearish view unless that view is continually being validated by the price action. That is, they are incapable of remaining confident in any opinion that doesn’t happen to conform to the current opinion of the manic-depressive mob. As a result they routinely get ‘sucked in’ following large price rises and ‘blown out’ following large price declines, as opposed to taking advantage of the mob’s proclivity to be wrong.

Therefore, as investors the challenge we all face is to strike a balance between staying the course in rough weather and preparing ourselves for the possibility that there could be unseen rocks up ahead.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Bearish divergences at gold-mining bottoms

A bullish divergence between the gold-mining sector of the stock market, as represented by the HUI and/or the XAU, and gold bullion involves the gold-mining sector having an upward bias while gold bullion has a downward bias or the gold-mining sector making a higher low while the bullion market makes a lower low. However, bullish divergences often don’t happen around major price bottoms. In fact, it is not uncommon for a major price bottom in gold-related investments to be preceded by a bearish divergence between the gold-mining indices and the metal. To be more specific, it is not uncommon for the gold-mining indices to be weak relative to gold bullion right up to the ultimate price bottom, at which point they suddenly become relatively strong.

Here are charts showing two historical examples of what I am referring to, either of which could be relevant to the present situation. The first chart shows the continuing downward bias in the XAU along with an upward bias in the US$ gold price in the weeks leading up to the XAU’s July-1986 bottom. The July-1986 bottom was followed by a huge multi-quarter rally in the gold-mining sector. The second chart shows the relentless decline in the HUI along with a flat gold price in the weeks leading up to the HUI’s November-2000 bottom. The November-2000 bottom was also followed by a huge multi-quarter rally in the gold-mining sector. The rally from the July-1986 bottom turned out to be the bear-market variety whereas the rally from the November-2000 bottom turned out to be the first leg of a new bull market, but from a practical speculation perspective an X% gain in a bear market is just as good as an X% gain in a bull market.

For comparison purposes, here is a chart showing the present situation.

It’s obviously too soon to know if the 10th August rebound in the gold-mining sector marked the start of a multi-quarter rally or even a 1-2 month rally, but the potential is there.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Can the US economy survive more of the Fed’s monetary support?

This post is a slightly-modified excerpt from a recent TSI commentary.

Everybody knows that the Fed will eventually hike its targeted interest rate. When it comes to rate hikes, the only unknowns involve timing. What hardly anybody knows is that the Fed’s interest-rate suppression has damaged the economy and that the longer it continues, the weaker the economy will get.

Based on the wording of last week’s FOMC statement it is still likely, but far from a certainty, that the first rate hike will happen in September. That is, the timing of the Fed’s first rate hike remains unknown. The bigger unknown, however, is the timing of the Fed’s second rate hike. The reason is that there could be a large gap between the first and second hikes as a jittery Fed takes its time assessing the effects of the first hike. It could also be a case of “one and done”.

There have recently been numerous comments in the press to the effect that the Fed should stay with its zero% target, the reasoning being that the US economy is not yet strong enough to cope with even the smallest of rate hikes. This is downright weird, given that the economy is supposedly now 6 years into a recovery from the 2007-2009 recession. Just to be clear, I am referring to comments that there SHOULD be no rate hike in the near future, not to comments that there WILL be no rate hike in the near future. The first type of comment is a policy recommendation based on the wrongheaded theory that keeping the Fed Funds Rate at zero will help the economy, whereas the second type of comment is based on the recognition that the Fed’s senior management is guided by wrongheaded theory.

Not to put too fine a point on it, only someone who is economically illiterate could believe an economy can be helped by forcing the risk-free short-term interest rate down to zero and holding it there for years. The reality is that when a central planner distorts price signals it causes investing errors in the affected parts of the economy, and when a central planner distorts the most important of all prices (the price of credit) it leads to investing errors across the entire economy. Many economists, and as far as I can tell all Keynesian economists, haven’t figured this out because their analyses are based on models that treat the economy as if it were an amorphous mass instead of what it is — an extremely complex network comprised of millions of individuals making decisions for their own reasons.

Strangely, the commentators on the financial world who claim that the Fed should continue its Zero Interest Rate Policy haven’t put two and two together. They haven’t twigged that it’s not a fluke that the greatest experiment in money-pumping and interest-rate suppression in the Fed’s history coincided with the weakest post-recession recovery since the 1930s. It’s not a fluke because the extraordinary stimulus is the main cause of the apparent inability of the economy to get out of its own way. A former Fed chairman (now blogger) and current Fed officials routinely take bows for having brought the economy back to health, and yet over the past three years the compound annual growth rate of real US GDP has been slightly less than 2%/year using the government’s estimate of “inflation” and probably around 0%/year using a more realistic estimate of “inflation”. And this 3-year period should have been the sweet spot of the post-2009 economic expansion!

To be fair, the failure to link the weakness of the recovery with the dramatic scale of the policy response is not actually strange. It is, in fact, completely understandable. After all, if the economic model to which you are totally committed is based on the assumption that money-pumping and interest-rate suppression give the economy a sustainable boost, then an unusually weak economy in the wake of aggressive intervention of this nature can only mean two things. It can only mean that the situation would have been even worse without the intervention and that the problem was too little, not too much, monetary accommodation.

It’s testament to the resilience of whatever capitalist elements remain that the Fed hasn’t yet driven the US economy into the ground. There must, however, be a limit to the amount of monetary accommodation (that is, to the amount of price falsification) that the economy can withstand. I wonder what that limit is. Unfortunately, by the looks of things we are going to find out.

Print This Post

Print This Post

The amazing inability to see the Fed’s money creation

The belief that the Fed’s QE (Quantitative Easing) does not directly boost the US money supply remains popular, even though it is obviously wrong. This is remarkable. It’s even more remarkable, however, that this wrongheaded belief is dearly held by some analysts who are generally astute, a fact I was reminded of when reading a recent post by Doug Noland.

The above-linked Noland post contains the following quote from Russell Napier. The quote is extraordinary due to a) the large number of errors that have been crammed into a few lines, b) the supreme confidence with which blatantly-wrong information is stated, and c) the fact that Russell Napier usually comes across as a smart analyst.

“Most investors still believe that we live in a fiat currency world. They believe central bankers can create as much money as they believe to be necessary. Such truths are on the front page of every newspaper, but they may contain just as much truth as the headlines of their tabloid cousins. A belief in this ability to create money is the biggest mistake in analysis ever identified by this analyst. The first reality it ignores is that money, the stuff that buys things and assets, is created by an expansion of commercial bank, and not central bank, balance sheets. The massively expanded central bank balance sheets have not lifted the growth in broad money in the developed world above tepid levels. Until that happens, developed world monetary policy must be regarded as tight and not easy.”

This quote is a mindboggling display of ignorance regarding the mechanics of the Fed’s QE, but Doug Noland describes it as “thoughtful and important analysis”. As they say in Thailand, oh my Bhudda! Doug Noland, another smart analyst, apparently also labours under false beliefs regarding the relationship between the Fed’s QE and the US money supply.

The Fed’s money-creation process is not that complicated. There’s certainly no good reason why professional financial-market analysts couldn’t or shouldn’t be familiar with it. I explained the process in some detail in a blog post on 16th February.

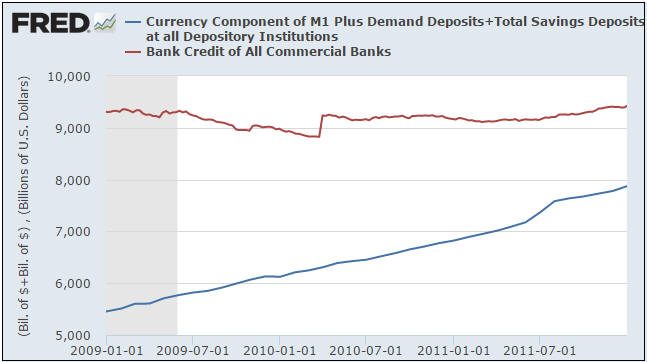

Moreover, even an analyst who doesn’t understand the mechanics of the QE process should be able to see, via a quick look at the money-supply and bank credit data, that there has been a lot more money creation in the US over the past several years than can be explained by the expansion of commercial bank balance sheets. For example, the red line on the following chart shows that from the beginning of 2009 through to the end of 2011 the total quantity of US commercial bank credit grew by only $100B (from $9.3T to $9.4T) while the blue line on the chart shows that over the same 3-year period the US money supply (currency in circulation outside the banking system + commercial-bank demand deposits + commercial-bank savings deposits) grew by $2.4T. If not from the Fed, where did the $2.3T of money-supply expansion that cannot be explained by commercial-bank credit expansion come from?

Not coincidentally, the amount by which the increase in commercial-bank credit falls short of the increase in the money supply is approximately the same as the increase in Fed credit. This is not a coincidence because the Fed created the money.

Print This Post

Print This Post

The gold supply-demand nonsense is relentless

In a blog post a couple of weeks ago I noted that it’s normal for large and fast price declines in the major financial markets to be accompanied by unusually-high trading volumes, meaning that it’s normal for large and fast price declines in the major financial markets to be accompanied by increased BUYING. I then wondered aloud as to why it is held up as evidence that something nefarious or strange is happening whenever an increase in gold buying accompanies a sharp decline in the gold price. Right on cue, ZeroHedge.com (ZH) has just published an article marveling — as if it were an inexplicable development — at how the recent sharp decline in the gold price was accompanied by an increase in buying.

As is often the case in the realm of gold-market analysis, the ZH article incorrectly conflates volume and demand. The demand for physical gold must always equal the supply of physical gold, with the price rising or falling by the amount needed to maintain the balance. If sellers are more motivated than buyers, then price will have to fall to restore the balance. The key point to understand here is that for every buyer there must be seller, and vice versa, so the purchase/sale of gold does not indicate a change in overall demand — it only indicates a fall in demand on the part of the seller and an exactly offsetting increase in demand on the part of the buyer. It is also worth noting — even though it should be obvious — that demand for physical gold cannot be satisfied by paper gold.

Trading in paper gold (gold futures, to be specific) clearly does have an effect on the price at which physical gold changes hands. The paper and physical markets are inextricably linked, but this link does not make it possible for the demand for physical gold to rise relative to the supply of physical gold in parallel with a falling price for physical gold.

What happens in the real world is that when the futures market leads the physical market higher or lower it changes the spread between the spot price and the price for future delivery. For example, when the gold price is being driven downward by speculative selling in the futures market, the price of gold for future delivery will fall relative to the spot price. In a period when risk-free short-term interest rates are being pegged at or near zero by central banks, this can result in the spot price becoming higher than the price of gold for delivery in a few months’ time. This creates a financial incentive for other operators in the gold market to buy gold futures and sell physical gold. For another example, when the gold price is being driven upward by speculative buying in the futures market, the price of gold for future delivery will rise relative to the spot price. This creates a financial incentive for other operators in the gold market to sell gold futures and buy physical gold.

The bullion banks are the “other operators”. They tend to focus on trading the spreads between the physical and futures markets. In doing so they position themselves to make a small percentage profit regardless of the price trend and therefore tend to be agnostic with regard to the price trend.

After harping on about the dislocation between the physical and paper gold markets, a dislocation that doesn’t actually exist but makes for good copy in some quarters, the above-mentioned ZH article moves on to the level of the CME (often still referred to as the COMEX) gold inventory. To the sound of an imaginary drumroll, the author of the article breathlessly points out that the amount of “registered” gold at the COMEX has dropped to a 10-year low and that the amount of “open interest” in gold futures is now at a 10-year high relative to the amount of “registered” gold.

The information is correct, but isn’t relevant other than as a sentiment indicator. It’s a reflection of what has happened to the price over the past few weeks and the increase in negativity that occurred in reaction to this price move. It is not evidence of physical-gold scarcity.

I currently don’t have the time to get into any more detail on the COMEX inventory situation. However, if you are interested in delving a little deeper you could start by reading the July-2013 article posted HERE. I get the impression that this article was written in response to the scare-mongering that ZH was doing on the same issue two years ago.

Thanks largely to the unprecedented measures taken by the senior central banks over the past few years, there have been many strange happenings in the financial world. However, the increased buying of physical gold in parallel with a sharply declining gold price and the reduction in COMEX “registered” gold cannot be counted among them.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Is the Fed privately owned? Does it matter?

The answer to the first question is ‘sort of’. The answer to the second question is no. The effects of having an institution with the power to manipulate interest rates and the money supply at whim are equally pernicious whether the institution is privately or publicly owned. However, if you strongly believe that the government can not only be trusted to ‘manage’ money and interest rates but is capable of doing so to the benefit of the economy, then please contact me immediately because I can do you a terrific deal on the purchase of the Eiffel Tower.

The fact is that the Federal Reserve would be a really bad idea regardless of whether it were privately owned or owned by the US government. The question of ownership is therefore secondary and the people who stridently complain about the Fed being privately owned are missing the critical point. In any case and as I explained in an article way back in 2007, the Fed is not privately owned in the true meaning of the word “owned”. For all intents and purposes, it is an agency of the US Federal Government.

In addition to the work of G. Edward Griffin referenced in my above-linked 2007 article, useful information about the Fed’s ownership can be found in a 2010 article posted at the Mises.org web site. This article approaches the Fed’s ownership and control from an accounting perspective, that is, by applying Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), and concludes that:

“…the Fed, when tested against GAAP as the Fed itself uses it in the Fed’s assessments of those it regulates, is a Special Purpose Entity of the federal government (or, according to the latest definition, is a Variable Interest Entity of the federal government). The rules of consolidation therefore apply, and the Fed must be seen as controlled by federal government, making it indivisibly part of the federal government. The pretence of independence is no more than that, a pretence.

There is, however, no denying that the banks have tremendous vested interest in influencing the policies of the Fed, nor that the power being so narrowly vested in the president makes him a special target for influence. Still, the power to control the Fed is not in the hands of its “owners” but firmly in the hands of the federal government and the president of the United States.”

It is clear that the Fed was established by the government at the behest of bankers with the unstated aim of facilitating the expansions of the government and the most influential banks. It is effectively a government agency, but due to the influence that the large banks have on the government it will, if deemed necessary by the Fed Chairman, act for the benefit of these banks at the expense of the broad economy. The happenings of the past eight years should have left no doubt about this.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Steep price declines and increased buying often go together

In numerous TSI commentaries over the years I’ve written about the confusion in the minds of many analysts regarding what constitutes gold supply and the relationship between supply, demand and price in the gold market. I’ve also covered the issue several times at the TSI Blog, most recently on 24th June in the post titled “More confusion about gold demand“. I’m not going to delve into this subject matter again today other than to use the example of last Monday’s trading in GDX (Gold Miners ETF) shares to further explain a point made in the past.

On Monday 20th July the GDX price fell by about 10% on record volume of 170M shares. Since every transaction involves both a purchase and a sale, more GDX shares were bought last Monday than on any other single day in this ETF’s history. And yet, this massive increase in buying occurred in parallel with a large price decline. How could this be?

Obviously, the large price decline CAUSED the massive increase in buying. Many holders of GDX shares were eager to get out and the price had to fall as far as it did to attract sufficient new buying to restore the supply-demand balance.

It’s normal for large and fast price declines in the major financial markets to be accompanied by unusually-high trading volumes, meaning that it’s normal for large and fast price declines in the major financial markets to be accompanied by increased BUYING. Most people understand this. So why is it held up as evidence that something nefarious is happening whenever an increase in gold buying accompanies a large decline in the gold price?

I can only come up with two plausible explanations. One is that many analysts and commentators switch off their brains before pontificating about gold. The other is that the relationship between gold supply, demand and price is deliberately presented in a misleading way to promote an agenda. I suspect that the former explanation applies in most cases, meaning that in most cases there’s probably more ignorance than malice involved.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Recommended Reading on the Iran Nuclear Treaty

Here are links to the two best articles I’ve read about the Iran nuclear treaty. The first is by David Stockman, an author, a blogger, a Wall Street veteran, and the Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan. The second is by Uri Avnery, a writer, the founder of the Gush Shalom peace movement, and a former member of Israel’s parliament. Although they tackle the issue from different perspectives, both articles are rich in historical information and insightful analysis. One thing Stockman and Avnery — and, as far as I can tell, everyone who is objective and well-informed on the subject — agree on is that Iran did not have a nuclear weapons program and probably had no intention of starting such a program.

http://davidstockmanscontracorner.com/all-praise-to-barrack-obama-hes-giving-peace-a-chance/

http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2015/07/17/uri-avnery-the-treaty/

Print This Post

Print This Post

Beware of bogus “inflation” indices

Every attempt to come up with a single number (a price index) that reflects the change in the purchasing power (PP) of money is bound to fail. The main reason is that disparate items cannot be added together and/or averaged to arrive at a sensible result. However, some price indices are less realistic than others. In particular, some well-meaning private-sector efforts to come up with a consumer price index (CPI) that does a better job than the official CPI have generated some of the least-plausible numbers.

One of the most popular alternatives to the official US CPI is the CPI calculated by Shadowstats.com. As I noted in a previous post, it always seemed to me that the Shadowstats number was derived by adding an approximately constant fudge-factor to the official (bogus) CPI to essentially arrive at another bogus number that, regardless of the message being sent by real-world experience, was always much larger than the official number. As I also noted at that time, economist Ed Dolan did some detective work to determine the cause of the strangely-large and fairly-constant difference between the Shadowstats number and the official number. It turned out that Shadowstats had made a basic calculation error that caused its version of the CPI to consistently be at least 4.5%/year too high even assuming the correctness of its own methodology.

Another alternative CPI is called the Chapwood Index. The components of this index were selected based on a survey of what Ed Butowsky’s friends and associates spend their money on (Ed Butowsky is the index’s creator). The prices of the 500 most commonly purchased items were then added together to generate the index. Not surprisingly, considering the methodology, the result is not a realistic measure of the change in the dollar’s PP or the cost of living. As evidence I point out that if the roughly 10%/year average increase in the general price level estimated by the Chapwood Index during 2011-2014 is correct, then the US economy’s real GDP must have been about 25% smaller at the end of 2014 than it was at the end of 2010*. In other words, if the Chapwood Index is an accurate reflection of PP loss then the US economy now produces about 25% less goods/services than it did four years ago. This is not remotely close to the truth.

When assessing the validity of economic statistics it’s important to use commonsense. A statistic isn’t valid just because it happens to be consistent with a narrative that you wholeheartedly believe.

*I arrive at this figure by approximately adjusting nominal GDP by the Chapwood Index, that is, by using the Chapwood Index as the GDP deflator.

Print This Post

Print This Post

A common currency is NOT a problem

A popular view these days is that the euro is a failed experiment because economically and/or politically disparate countries cannot share a currency without eventually bringing on a major crisis. Another way of expressing this conventional wisdom is: a monetary union (a common currency) cannot work without a fiscal union (a common government). This is unadulterated hogwash. Many different countries in completely different parts of the world were able to successfully share the same money for centuries. The money was called gold.

The fact that a bunch of totally disparate countries in Europe have a common currency is not the problem. The problem is the central planning agency known as the European Central Bank (ECB), which tries to impose a common interest rate across these diverse countries/economies. This leads to even more distortions than arise when such agencies operate within a single country (the Fed in the US, for example), which is really saying something considering the distortions caused by the Fed and other single-country central banks.

I’m reticent to pick on John Hussman, because his analysis is usually on the mark. However, his recent comments on the Greek crisis and its supposed relationship to a common currency make for an excellent example of the popular view that I’m taking issue with in this post. Here is the relevant excerpt from the Hussman commentary, with my retorts interspersed in brackets and bold text:

“The prerequisite for a common currency is that countries share a wide range of common economic features. [No, it isn't! Money isn't supposed to be a tool that is used to manipulate the economy, it is supposed to be a medium of exchange.] A single currency doesn’t just remove exchange rate flexibility. It also removes the ability to finance deficits through money creation, independent of other countries. [Removing the ability to finance deficits through money creation is a benefit, not a drawback.] Moreover, because capital flows often respond more to short-term interest rate differences (“carry trade” spreads) than to long-term credit conditions, the common currency of the euro has removed a great deal of interest rate variation between countries. [No, the ECB has done that. In the absence of the ECB, interest rates in the euro-zone would have correctly reflected economic reality all along.] It may seem like a good thing that countries like Greece, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and others have been able to borrow at interest rates close to those of Germany for nearly two decades. But that has also enabled them to run far larger and more persistent fiscal deficits than would have been possible if they had individually floating currencies. [This is completely true, but it is the consequence of a common central bank, not a common currency.]

The euro is essentially a monetary arrangement that encourages and enables wide differences in economic fundamentals between countries to be glossed over and kicked down the road through increasing indebtedness of the weaker countries in the union to the stronger members. [The ECB, not the common currency, encourages this.] This produces recurring crises when the debt burdens become so intolerable that even short-run refinancing can’t be achieved without bailouts.

Greece isn’t uniquely to blame. It’s unfortunately just the first country to arrive at that particular finish line. Greece is simply demonstrating that a common currency between economically disparate countries can’t be sustained without continuing subsidies from the more prosperous countries in the system to less prosperous ones. [If this is true, how did economically disparate countries around the world use gold as a common currency for so long without the more prosperous ones having to subsidise the less prosperous ones?]“

Money is supposed to be neutral — a medium of exchange and a yardstick. It is inherently no more problematic for totally disparate countries to use a common currency than it is for totally disparate countries to use common measures of length or weight. On the contrary, there are advantages to the use of a common currency in that trading and investing are made more efficient.

In conclusion, the problem is the central planning of money and interest rates, not the fact that different countries use the same money. It’s a problem that exists everywhere; it’s just that it is presently more obvious in the euro-zone.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Gold Commitments of Traders (COT) Nonsense

A lot of nonsensical commentary gets written about the Commitments of Traders (COT) data for gold (and silver). The information in the COT reports can be used as an indicator of gold-market sentiment. Nothing more, nothing less. It cannot validly be used to support the theory that “commercial” traders (primarily bullion banks) have been conducting a long-term price-suppression scheme.

One of the most important points to understand with regard to the positioning of traders in the gold futures market is that the group known as speculators drives the short-term price trends. This is made apparent by the following chart, which was created by Saxo Bank and linked at the article posted HERE. The chart clearly shows that, with only a few minor discrepancies, over the past three years the net position of speculators in the COMEX futures market (the black line) has moved with the gold price (the red line). More specifically, it shows that speculators start adding to their collective net-long position at price lows and continue to add until the price makes a short-term top, at which point they become net sellers and their collective net-long position begins to decline. The process is self-reinforcing, in that a rising price prompts buying and a falling price prompts selling by the trend-followers within the speculating community. Note that a chart stretching back well beyond 2012 would show the same relationship.

As is the case in any market, the speculators in gold tend to be most bullish/optimistic just prior to significant price tops and most bearish (or least optimistic) just prior to significant price bottoms. That’s why the COT information can be used as a sentiment indicator. And as with most sentiment indicators, the COT’s weakness is that there are no absolute benchmarks. For example, while we can be confident that a short-term price bottom for gold will coincide with a relatively low level for the speculative net-long position in COMEX gold futures, there’s no way of knowing that level in advance.

If we lump large speculators and small (non-reporting) traders together under the “speculators” label, then the “commercial” position is simply the inverse of the speculative position. In order for speculators to become net-long by X contracts, commercials must become net-short by X contracts. This is a function of mathematics, since the futures market is a zero-sum game. Furthermore and as discussed above, we know that it’s the group known as “speculators” that’s driving the process since the price has a strong positive correlation with this group’s net-long position.

Therefore, getting angry with commercials for shorting gold futures — as some gold bulls do — is equivalent to getting angry with speculators for buying gold futures, since speculators, as a group, cannot possibly increase their long exposure in gold futures unless commercials, as a group, increase their short exposure.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Currency devaluation, the most destructive policy of all

With the return to a currency that can be devalued at will by its own government being spoken of in some quarters as part of the solution to Greece’s economic malaise, this is an opportune time to reprint a piece about currency devaluation that was originally included in a TSI commentary in July of last year. The gist of the piece is that currency devaluation cannot possibly help, but it can certainly hurt. Here it is, beginning with a quotation from a surprising source.

“Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the existing distribution of wealth*. Those to whom the system brings windfalls, beyond their deserts and even beyond their expectations or desires, become ‘profiteers’, who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished, not less than of the proletariat. As the inflation proceeds and the value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.

Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and it does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

The above quotation is perfect. It does such a good job of succinctly describing why currency devaluation is a destructive policy, both economically and socially, that it could have been written by Mises. Strangely, therefore, it was written by Keynes**.

It seems that Keynes understood the problems wrought by policies designed to debauch (devalue) the currency, but such understanding is nowhere to be seen among his modern-day followers. Instead, the modicum of sense contained in the writings of Keynes has been discarded by the Keynesians of today in favour of a total focus on “aggregate demand”. If you wrongly believe the economy to be an amorphous blob driven by changes in “aggregate demand”, then you are looking at the economy through a lens that creates such a distorted view of the world that what you perceive is the opposite of reality. When looking through such a lens, currency-devaluation policy can appear to be justifiable.

One of the most common ‘justifications’ for currency devaluation is that it makes local exporters more competitive. The problem, as explained in previous TSI commentaries, is that it can only benefit exporters at the EXPENSE of consumers and importers. There can be no net benefit to the economy. Moreover, the beneficiaries only benefit temporarily. The reason is that a sustained reduction in a currency’s value on the foreign exchange market requires relatively high monetary inflation, which leads to rises in domestic prices that not only counteract any benefit to exporters from the exchange-rate decline, but also distort relative prices in a way that makes the overall economy less efficient.

Related to the “we need to devalue our currency to make our exports more competitive” idiocy is the handwringing that happens in reaction to trade deficits. According to neo-Keynesian orthodoxy, every dollar that flows out of the US due to a trade deficit is a dollar less of spending within the domestic economy, which, in turn, leads to a weaker domestic economy and higher unemployment. In reality, however, every dollar that flows out due to a trade deficit eventually returns as some form of investment. That’s why the $500B+ annual US trade deficit has not reduced the US money supply. As Joseph Salerno (a good economist) explains in a 17th July article, trade-deficit dollars get invested by foreigners in US stocks, bonds, real estate such as buildings and golf courses, and financial intermediaries like banks and mutual funds, with many of the dollars ultimately being lent to or invested in US businesses. These businesses then spend the dollars on paying wages and buying real capital goods like raw materials, plants and equipment, and software. The point is that the flow of spending in the US economy is not diminished by a negative trade balance, but merely re-routed. There will be a redirection of labor and capital out of export industries into industries producing consumer and capital goods for domestic use, with no net loss of jobs. A net loss of jobs will, however, come about due to policies put in place to ‘fix’ a perceived trade-deficit problem.

Another common ‘justification’ for currency devaluation is that it lowers real wages and thus gets around the problem that the nominal price of labour tends to be ‘sticky’. The idea is that nominal wage rates are excessively slow to fall in response to reduced demand for workers, and that currency devaluation helps by surreptitiously reducing the real price of labour. The first point to note here is that the ‘stickiness’ of wages was never a problem in the US prior to the 1930s, when the Hoover and Roosevelt Administrations took steps to prevent wages from falling in response to a severe economic downturn. A second and related point is that government payments to the unemployed can reduce the incentive for able-bodied people to accept lower wages to re-enter the workforce. In other words, if nominal wages are problematically ‘sticky’ it is because of government intervention, not the free market. Third, the knowledge that modern money relentlessly loses purchasing power over time would tend to make nominal wages ‘stickier’ than they would otherwise be. In other words, the policy designed to address the perceived problem of ‘sticky’ wages actually contributes to the problem. In any case, these points are not critically relevant. Regardless of whether wages really are ‘sticky’ and regardless of the cause of the supposed problem, ‘sticky’ wages could never logically justify a policy that must ultimately weaken the economy.

The primary problem with currency devaluation is that it leads to non-uniform changes in prices throughout the economy. In effect, the implementers of devaluation policy send false price signals into the economy, which leads to more investing mistakes than would otherwise happen. As a result of the greater number of investing mistakes, there ends up being less wealth. Furthermore, the smaller pool of wealth will be redistributed by the devaluation policy, often in a way that is so obviously unfair that it provokes calls for new interventions and punitive taxes. It therefore puts the economy on the proverbial “slippery slope”.

In summary, Keynes wasn’t right about much, but early in his career he was absolutely right about currency devaluation. It is a process that engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and it does so in a manner that not one man in a million will be able to diagnose.

*The undeserved wealth distribution caused by currency devaluation policy is the root cause of today’s fixation on “inequality”. Unfortunately, none of the most popular writers on this topic understand the cause of the perceived problem.

**The quotation is from Chapter 6 of Keynes’ 1919 book titled “The Economic Consequences of the Peace”.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Can the Fed do more?

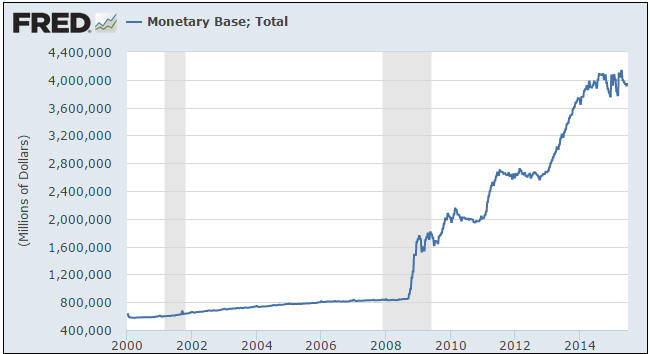

It’s not an overstatement to say that over the 6-year period beginning in September-2008, the US Federal Reserve went berserk with its Quantitative Easing (QE). The following chart shows that the US Monetary Base, an indicator of the net quantity of dollars directly created by the Fed*, had a gentle upward slope until around August of 2008, at which point it took off like a rocket. More specifically, the Monetary Base gained about 30% during the 6-year period leading up to September of 2008 and then quintupled (gained 400%) over the next 6 years. Is it therefore fair to say that the Fed has now ‘shot its load’ and will be unable to do much in reaction to the next financial crisis and/or recession?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. The sad truth is that the Fed is not only capable of doing a lot more, it will almost certainly pump a lot more money into the economy the next time its senior management decides that the financial or economic wheels are falling off.

The Fed is capable of doing a lot more because it is not yet remotely close to running out of things to monetise. For example, the US Federal debt is presently about $18.1T and will probably top $20T within the next two years. This means that there is plenty of scope for the Fed to add to its current $2.5T stash of Treasury securities. Also, the Fed is not strictly limited in what it can monetise. Up until now it has been monetising Mortgage-Backed and Agency securities in addition to Treasury securities, but it could branch out into other asset-backed securities (those backed by auto loans or student debt, for instance), municipal bonds, investment-grade corporate bonds, and equity ETFs. If the situation were perceived to be sufficiently dire it could even change the rules to allow itself to monetise commercial and residential real-estate.

And the Fed almost certainly will do a lot more on the money-pumping front in the face of future economic and/or stock market weakness, because it has not only failed to learn the right lessons from the events of the past 15 years, it has learned exactly the wrong lessons. Rather than learning that injecting more money into the economy in an effort to mitigate the fallout from a busted bubble leads to a bigger bubble, a bigger bust, greater hardship and structural economic weakness, its senior management is convinced that the QE and interest-rate-suppression programs provided a substantial net benefit to the overall economy. Given this conviction in the righteousness of its previous actions, why wouldn’t the Fed do more of the same if the perceived need were to arise in the future? The answer, of course, is that it would. And it will.

In conclusion, those who think that the Fed is incapable of further monetary expansion do not have a good understanding of the situation, and those who believe that the Fed could do more, but will choose not to as the result of newfound financial prudence or concern for the well-being of savers, are naive.

*The Monetary Base is made up of currency (physical notes and coins) in circulation outside the banking system plus bank reserves. Bank reserves aren’t counted in the True Money Supply, but for every dollar of reserves created by the Fed as part of its QE the Fed also adds a dollar of money to the economy via a deposit into the demand account of a Primary Dealer. That is, QE results in the one-for-one creation of money and reserves. For a more detailed explanation, refer to my 16th February 2015 post.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Does “Austrian Economics” predict inflation or deflation?

The answer to the above question is no, meaning that “Austrian Economics” makes no prediction about whether the future will be inflationary or deflationary. That’s why some adherents to “Austrian” economic theory predict inflation while others predict deflation. A good economic theory can give you insights into the likely short-term, long-term, direct and indirect effects of policy choices, but it doesn’t tell you what will happen regardless of future choices and events. I’ll try to explain using two well-known quotes from Ludwig von Mises, the most important economist of the “Austrian” school.

Here’s the first quote:

“There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.”

The first sentence of this quote is sometimes taken out of context as part of an argument in favour of deflation. It could be construed, if considered in isolation, as a statement that a period of deflation MUST follow a credit-fueled boom. However, no good economist, let alone the greatest economist of the past century, would ever claim that price deflation was inevitable regardless of what was happening to the money supply. To do so would be to claim that the law of supply and demand did not apply to money. In the real world there will always be a link between money supply and money purchasing power. The link is complex, but it will always be possible to reduce the purchasing power of money by increasing its supply.

The second sentence provides the necessary clarification. In essence, it says that a boom fueled by a great credit expansion can collapse in one of two ways. The first is by voluntarily ending the credit expansion. This would generally involve doing nothing or very little while a corrective process ran its course. The other is by relentlessly persisting with credit expansion in an effort to avoid a crisis. This would lead to a total catastrophe of the currency system, meaning it would lead to the currency becoming completely worthless.

The first of the two alternatives is the deflation path. The second is the inflation path (endless rapid monetary inflation leading to hyperinflation and, eventually, to the currency becoming so devalued it no longer functions as money). Note that money can only collapse due to inflation. Deflation makes money more valuable.

The Fed is presently heading down the inflation path, but it doesn’t have to stay on this path. A change of direction is still possible.

Now for the other Mises quote mentioned in the opening paragraph:

“This first stage of the inflationary process may last for many years. While it lasts, the prices of many goods and services are not yet adjusted to the altered money relation. There are still people in the country who have not yet become aware of the fact that they are confronted with a price revolution which will finally result in a considerable rise of all prices, although the extent of this rise will not be the same in the various commodities and services. These people still believe that prices one day will drop. Waiting for this day, they restrict their purchases and concomitantly increase their cash holdings. As long as such ideas are still held by public opinion, it is not yet too late for the government to abandon its inflationary policy.

But then, finally, the masses wake up. They become suddenly aware of the fact that inflation is a deliberate policy and will go on endlessly. A breakdown occurs. The crack-up boom appears. Everybody is anxious to swap his money against ‘real’ goods, no matter whether he needs them or not, no matter how much money he has to pay for them. Within a very short time, within a few weeks or even days, the things which were used as money are no longer used as media of exchange. They become scrap paper. Nobody wants to give away anything against them.”

The gist is that if the inflation policy continues for long enough then a psychological tipping point will eventually be reached. At this tipping point the value of money will collapse as people rush to exchange whatever money they have for ‘real’ goods. Mises refers to this monetary collapse as the “crack-up boom”. Prior to this point being reached it will not be too late to abandon the inflation policy.

Today, the US is still immersed in the first stage of the inflationary process. If it continues along its current path then a “crack-up boom” will eventually occur, but there is no way of knowing — and “Austrian” economic theory makes no attempt to predict — when such an event will occur. If the current policy course is maintained then the breakdown could occur within 2-5 years (it almost certainly won’t happen within the next 2 years), but it could also be decades away. Importantly, there is still hope that policy-makers will wake up and change course before the masses wake up and trash the currency.

In conclusion, “Austrian” economic theory helps us understand the damage that is caused by monetary inflation and where the relentless implementation of inflation policy will eventually lead. That is, it helps us understand the direct and indirect effects of monetary-policy choices. It doesn’t, however, make specific predictions about whether the next few years will be characterised by inflation or deflation, because whether there is more inflation or a shift into deflation will depend on the future actions of governments and central banks. It will also depend on the performances of financial markets, because, for example, a large stock-market decline could prompt a sufficient increase in the demand for cash to temporarily offset the effects of a higher money supply on the purchasing power of money.

The upshot is that regardless of how the terms are defined, at this stage neither inflation nor deflation is inevitable.

Print This Post

Print This Post