The US yield curve is considered to be a good leading indicator of US recession, with an inversion of the curve invariably occurring prior to the start of a recession. However, the Wolf Street article posted HERE questions the yield curve’s reliability. The article notes that part of the US yield curve recently ‘uninverted’, which is true. What’s not true is the claim in the article that since 1998 the US yield curve failed twice by warning of recessions that didn’t occur.

According to the article, the yield curve’s 2019 inversion was a failure because even though there was a recession in 2020, the recession was the result of a pandemic and not a business cycle downturn. This is strange reasoning, to put it mildly.

The only way that you could argue logically that the yield curve’s 2019 inversion was a failure would be if you could re-run history to show that in the absence of the COVID pandemic there would not have been a recession. Since this is not possible, the 2019 inversion should not be viewed as a failure. Either it was a success or it should not be counted.

Also according to the article, there was a yield curve inversion in 1998 that was not followed by a recession.

The problem here stems from interpreting a multi-day spike into inversion territory as a recession signal. This problem goes away if you base your analysis on monthly closing or monthly average prices, which generally is what should be done with long-term indicators.

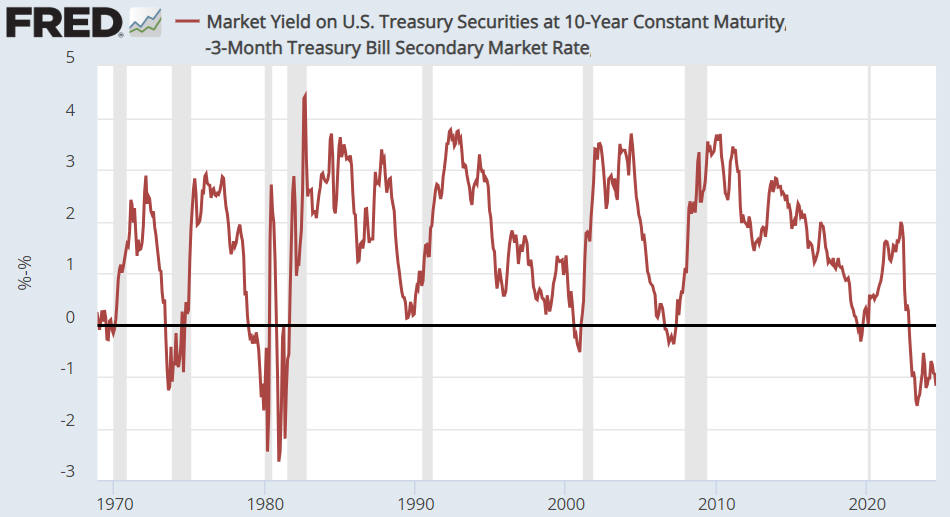

Here is a monthly chart showing that since the late-1960s every inversion of the US 10year-3month yield spread was followed by a recession. Consequently, if this cycle’s yield curve inversion does not lead to a recession then it will be the first failure of this type (the first false positive) in more than 50 years. Note, though, that the monthly chart of the 10year-3month yield spread shows that there was no yield curve inversion prior to the 1990 recession, so this could be viewed as a false negative.

Regardless of whether or not this cycle’s yield curve inversion leads to a recession, a yield curve inversion/uninversion clearly isn’t a useful trading signal. The time between the warning signal and the projected outcome is simply too long and too variable.