[This blog post is an excerpt from a TSI commentary published on 22nd January 2023]

It goes without saying that the early stage of every large rally contains a break above resistance and the early stage of every large decline contains a break below support. However, most upside breakouts are not followed by large rallies and most downside breakouts are not followed by large declines. More interestingly, it is not uncommon for the best rallies to begin shortly after breaks BELOW obvious support and for the largest declines to begin shortly after breaks ABOVE obvious resistance. The reason is that breaching obvious resistance/support shakes out many weak-handed speculators and in doing so can create a sentiment platform capable of launching a substantial move in the opposite direction.

There are countless examples of the phenomenon described above, including gold’s performance over the past several months. Last September-October the US$ gold price breached important and obvious support defined by the lows of the preceding two years, but the breach of support did not have bearish implications. Instead, it marked the END of a 2-year bearish trend and in all likelihood ushered in a cyclical bull market.

We are revisiting this topic today because the S&P500 Index (SPX) is positioned such that it could soon generate a misleading signal in the form of a break above obvious resistance.

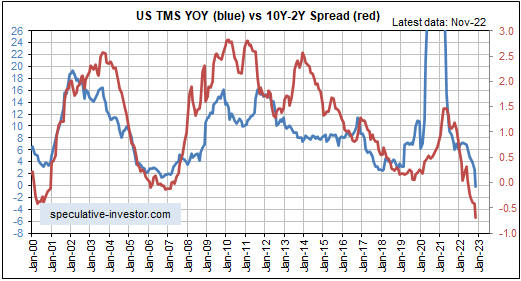

The potential upside breakout is associated with the downward trend-line drawn on the following daily SPX chart. Every chart-watcher and his dog are paying close attention to this trend-line and many of them undoubtedly would interpret a move above it as evidence that the bear market is over. However, the historical record suggests that the bear market won’t end until many months after the monetary trend becomes favourable, which probably means no sooner than the final quarter of this year.

There are fundamental differences between the present day and any previous period, but in price-action terms the current equity bear market has, to date, been similar to the equity bear market of 2000-2002. Both bear markets followed spectacular bubbles that were focused on tech stocks, involved stair-step declines rather than liquidity-driven collapses, and contained signs of internal strength after the initial multi-month declines.

Interestingly, during the course of the 2000-2002 bear market the SPX broke above a downward trend-line that is not unlike the trend-line drawn on the above chart. As illustrated below, about a week after the ‘bullish’ upside breakout in March-2002 the SPX commenced its largest decline of the bear market.

We don’t know that the SPX will break above its downward trend-line in the near future, although it stands a good chance of doing so. The point we want to stress today is that if the trend-line is breached it will not imply that the bear market is over or even that there will be significant gains over the weeks immediately ahead. On the contrary, an upside breakout could lead quickly to the best opportunity to date to enter bearish speculations.

Print This Post

Print This Post