[This blog post is an excerpt from a recent commentary published at TSI]

This is a follow-up to our 25th April piece titled “Inconvenient Facts” in which we summarised some of the issues that are ignored or brushed over by many proponents of a fast transition to a world dominated by renewable energy sources. The follow-up was prompted by a recent RealVision.com interview of Wil VanLoh, the CEO of Quantum Energy Partners, by Kyle Bass. The charts displayed below were taken from this interview.

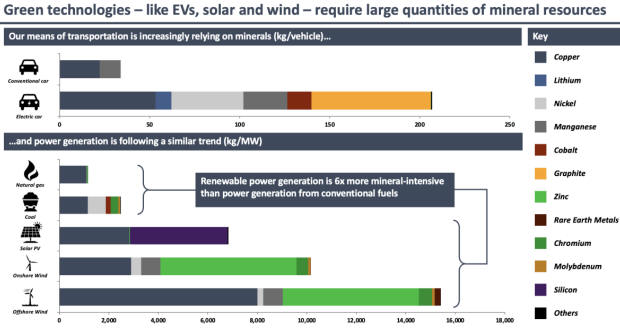

To summarise the summary included in our earlier piece, it takes a lot of energy and minerals to build renewable energy systems and it takes years for a renewable energy system to ‘pay back’ the energy that was used to build it. Consequently, achieving the energy transition goals set by many governments will require increasing production of fossil fuels for at least the next ten years, which, in turn, will require substantially increased investment in fossil fuel production and distribution (pipelines, terminals, storage facilities and ships). In addition, achieving today’s energy transition goals will necessitate substantially increased production of certain minerals, meaning that it will require more mining.

With regard to the need for more mining to bring about the Sustainable Energy Transition (SET), the top section of the following chart compares the quantities of minerals required to build a conventional car with the quantities required to build an electric car. The bottom section of the same chart does a similar comparison of fossil-fuel (natural gas and coal) power generation and renewable (solar, on-shore wind and off-shore wind) power generation.

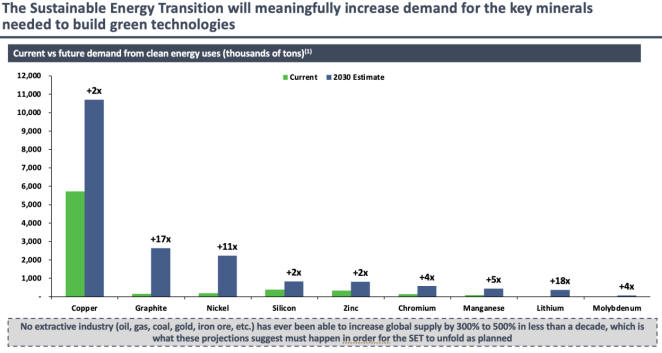

The next chart illustrates the increase in the production of several minerals that will have to happen by 2030 to achieve the current energy transition goals. Of particular interest to us, it shows that over the next eight years copper and zinc production will have to double, manganese production will have to increase by 5-times, nickel production will have to increase by 11-times and lithium production will have to increase by 18-times.

On a related matter, mining is an energy-intensive process. Moreover, the bulk of the increased mining required to meet the current SET goals will occur in places where the only economically-viable sources of energy will be fossil-fuelled power stations or local diesel-fuelled generation. This means that the increase in mining required for the energy transition will, itself, require increased production of coal, natural gas and diesel.

Soaring prices of oil, natural gas, coal and oil-based products (gasoline and diesel) have focused the attention of senior Western politicians on the urgent need for more oil and natural gas production. However, today’s supply shortages are due to a decade of under-investment in hydrocarbon production, which, in turn, is a) the result of political and social pressure NOT to invest in such production, b) a problem that even in a best-case scenario will take many years to resolve, and c) a problem that will be exacerbated by chastising oil companies and threatening government intervention to cap prices.

If it were possible to do so, ‘greedy’ oil and oil-refining companies would be very happy to flip a switch and increase production to take advantage of current high prices. The reality is that it isn’t possible and that increasing production to a meaningful extent will require large, long-term investments. But why should these companies take the risks associated with major investments to boost long-term supply when they continue to be pressured by both governments and their own shareholders to prioritise reduced carbon emissions above all other considerations and when there is enormous uncertainty regarding future government energy policy?

Print This Post

Print This Post