Janet Yellen has quipped that the Fed’s balance-sheet reduction program, which will start at $10B/month in October-2017 and steadily ramp up to $50B/month over the ensuing 12 months, will be as boring as watching paint dry. However, like many financial-market pundits she is underestimating the effects of the Fed’s new monetary plan.

In the old days, hiking the Fed Funds rate (FFR) involved reducing the quantity of bank reserves and the money supply, but that is no longer the case. Hiking the FFR is now achieved by raising the interest rate that the Fed pays to banks on reserves held at the Fed, which means that hiking the FFR now leads to the Fed injecting reserves into the banking system. This was explained in previous blog posts, including “Tightening without tightening (or why the Fed pays interest on bank reserves)“, “New tools for manipulating interest rates“, and “Loosening is the new tightening“.

In other words, under the new way of operating that was implemented in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, hiking the FFR does not tighten monetary conditions. In fact, given that hikes in the FFR now result in more money being pumped INTO the banking system, an argument could be made that a hike in the FFR is now more of a monetary loosening than a monetary tightening. It is therefore not surprising that the rate hikes implemented by the Fed over the past two years had no noticeable effect on anything.

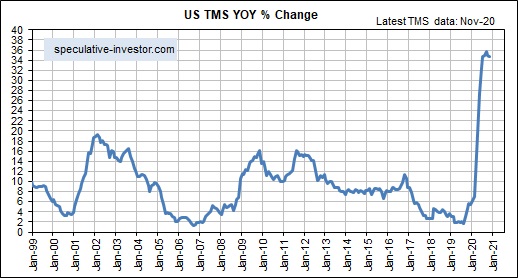

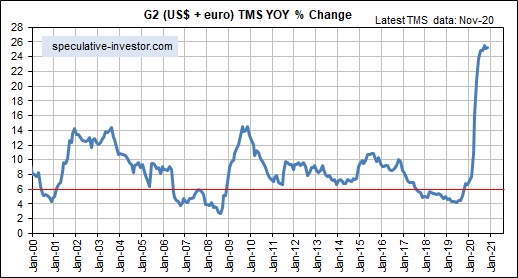

I mentioned in a blog post a few weeks ago that there has been a significant tightening of US monetary conditions since late last year, but this has not been due to the actions of the Fed. Rather, the rate of US monetary inflation has dropped substantially over the past 10 months due to a decline in the pace of commercial-bank credit expansion. As an aside, the substantial drop in the US monetary inflation rate would have affected the stock market in a bearish way by now if not for the offsetting effect of rapid euro-zone monetary inflation.

The Fed’s first genuine step along the monetary tightening path will happen within the next few weeks when it begins to shrink its balance sheet*. When this happens it will mark a momentous change in the monetary backdrop, and given that it will happen after the US monetary inflation rate has already tumbled it is likely to have financial-market consequences that are far more exciting than watching paint dry.

*The fact that the balance-sheet reduction will take place via the non-reinvestment of proceeds received from maturing securities rather than the selling of securities is neither here nor there. An X$/month balance-sheet reduction is an X$/month balance-sheet reduction, regardless of how it occurs.

Print This Post

Print This Post