When I say that China’s bubble has burst I’m not referring to the recent large decline in the stock market. Although the stock market was the focal point of Chinese speculation during 2006-2007 and during an 8-month period beginning last October, in the grand scheme of things it is no more than a sideshow. Unfortunately, the stock market crash is a minor issue compared to the main problem.

The main problem is that China’s economy is the scene of a credit bubble of historic proportions. That this is indeed the case is evidenced by the following charts from an article posted by Steve Keen last week.

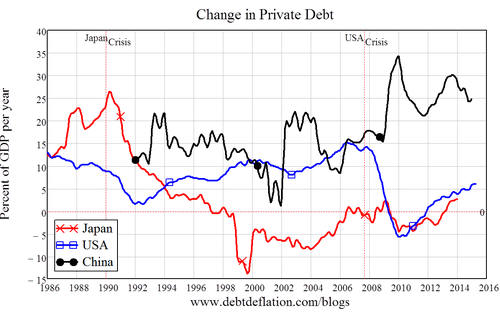

The first chart shows the ratio of private debt to GDP over the past 30 years for the US (the blue line), Japan (the red line) and China (the black line). In particular, the chart shows that China’s current private-debt/GDP is well above the 30-year high for US private-debt/GDP, which suggests that China’s private-debt bubble is bigger than the US bubble that burst in 2007-2008.

The above chart indicates that China’s private-debt bubble isn’t yet as big as the bubble that popped in Japan in the early-1990s, but the next chart shows that the rate of private-debt growth in China over the past several years is far in excess of anything that happened in either Japan or the US in the years leading up to their respective bubble peaks.

There’s no telling how big a credit bubble will become before it bursts, so the fact that China’s economy is host to one of history’s greatest-ever credit bubbles doesn’t mean that the bubble won’t continue to inflate for years to come. However, there are clues that China has transitioned to the long-term bust phase of the monetary-inflation-fueled boom-bust cycle, that is, there are clues that China’s bubble has burst.

Chief among these clues is the large and accelerating flow of money out of China. So-called “capital outflows” from China have been increasing over the past 12 months and according to a recent Telegraph article amounted to $190B over just the past 7 weeks.

Pressure caused by the flow of “capital” out of China led to the small Yuan devaluation that garnered huge media coverage a couple of weeks ago. In an effort to maintain the semblance of stability, if China’s government had been able to delay the inevitable and keep the Yuan propped-up at an artificially-high level for longer, it would have done so. In other words, the devaluation was a tacit admission by China’s government that the pressure caused by capital outflows had become too great to resist.

Once a private-sector credit bubble begins to unwind, the process is irreversible. The standard Keynesian remedy is to replace private debt with public debt, but all this does is add new distortions to the existing distortions.

Print This Post

Print This Post