[This blog post is an excerpt from a TSI commentary published last week]

Does the rapid rise in the bitcoin price and the slide in the gold price over the past several months indicate that bitcoin is sapping demand from gold? The short answer is no, because the performance of gold makes sense without reference to bitcoin. A longer answer requires discussing the major differences between gold and bitcoin.

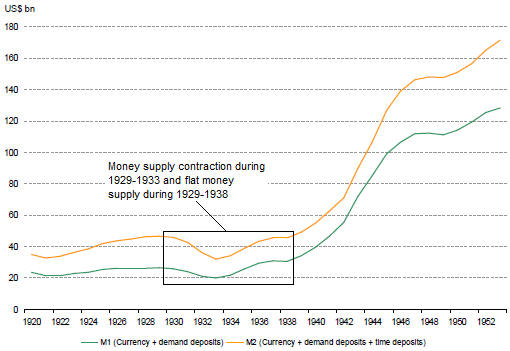

The differences between gold and bitcoin are far more significant than any similarities. Neither is money in the only practical definition of the term (the general medium of exchange), but gold trades like money. Of particular relevance, the demand to hold money (and therefore gold) tends to rise during ‘busts’ and fall during ‘booms’. A consequence is that gold generally doesn’t do well when the stock market is ‘bubbling’.

Bitcoin, in contrast, trades like an illiquid commodity, because that’s what it is. No money or widely-used currency in history has ever traded the way bitcoin has traded and it’s reasonable to assume that none ever will.

The spectacular rise in the bitcoin price over the past 10 months is related to the bubble that has formed in the stock market and the associated spectacular rises in the stock prices of the companies with which the public has become infatuated. Obviously, Tesla (TSLA) is such a company. The following chart compares the bitcoin price with the Tesla share price.

Bitcoin ‘bubbled with the stock market in 2020. It also ‘bubbled’ with the stock market during 2017 and if it had been around at the time it almost certainly would have ‘bubbled’ with the stock market during 1999-2000, whereas the desire to hold money or gold diminishes when the prices of speculative assets are rocketing upward in real terms. Who wants to own gold when the record of the past 1 year, 5 years and 10 years ‘proves’ that you will do much better by owning QQQ (the NASDAQ100 ETF)?

It’s likely that the gold price will embark on its next intermediate-term advance at around the time that the bitcoin price reaches an important top. That’s not because bitcoin has been draining demand from gold, but because a top for the bitcoin price probably will occur at around the same time as a top for speculation in general and a trough in the desire to hold cash reserves.

We still could be a few months away from a major top for speculation in general, so at this time it is still better to be ‘long’ consumable commodities and speculative assets than to be ‘long’ gold.

Print This Post

Print This Post