[This blog post is an excerpt from a recent TSI commentary]

For 36 years the yield on the 10-year T-Note moved lower within the channel drawn on the following chart. Depending on how the lines are drawn, an upside breakout from this channel may or may not have just occurred. If an upside breakout has occurred or occurs later this year following a pullback over the next few months, would this confirm the end of the secular downward trend in interest rates?

It’s not that simple. Obviously, an upside breakout from the long-term channel would be consistent with the trend having changed from down to up, but prices often generate misleading signals via failed breaks below chart-based support or above chart-based resistance. However, there are fundamental reasons to be confident that a long-term trend change has occurred.

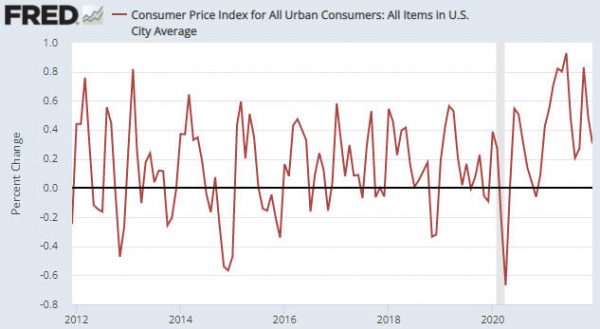

The fundamental reasons revolve around the monetary and fiscal responses to the pandemic in 2020, which in combination created such a massive inflation problem that the forces putting downward pressure on interest rates have been overwhelmed. The official response to COVID wasn’t the straw that broke the camel’s back, it was the bazooka that blew the camel to pieces.

There were two parts to the official COVID response that set the stage for a directional change in the secular interest-rate trend. First, there was the imposition of widespread lockdowns that caused the prices of most commodities to collapse and prompted a panic into Treasury securities, leading to a blow-off move to the downside in Treasury yields. Second, there was the effort by the Fed and the government to mitigate the short-term pain stemming from the lockdowns, which involved expanding the total US money supply by 40% in less than a year and ‘showering’ the population with money. The effort was very successful at mitigating short-term pain, but at the expense of economic progress and living standards beyond the short-term. The adverse effects of the actions taken to reduce/eliminate short-term pain during 2020 and the first half of 2021 will be evident for many years to come.

We thought that the secular downward trend in interest rates had ended shortly after the blow-off move in Q1-2020, and this opinion has been subsequently supported by a lot of evidence. However, all secular trends have tradable countertrend moves. We are anticipating a tradable move to the downside in US government bond yields over the next several months.

Print This Post

Print This Post