[This blog post is an excerpt from a commentary published at speculative-investor.com on 27th August 2023]

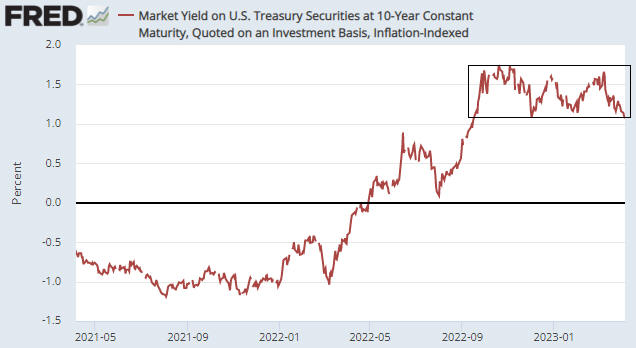

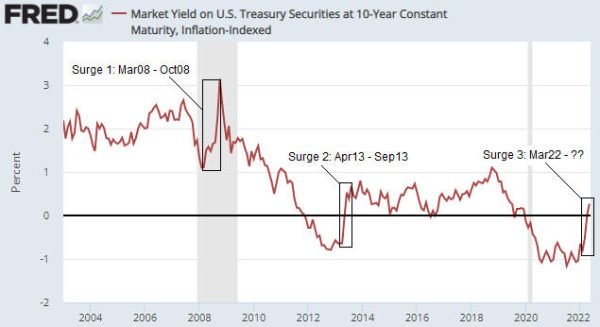

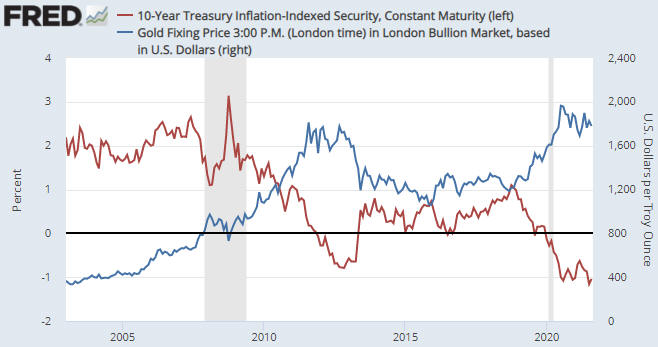

We’ve noted in previous commentaries how well the US$ gold price has held up given the rise in real US interest rates as indicated by the 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) yield. We are referring to the fact that the 10-year TIPS yield, a long-term chart of which is displayed below, made a 14-year high of 2.00% early last week before pulling back a little, whereas the US$ gold price has retraced less than half of its up-move from its Q4-2022 low. We often say that everything is linked, and in this case the likely linkage (the explanation for gold’s resilience) is the nature of the recent T-Bond sell-off.

Chart Source: https://www.cnbc.com/quotes/US10YTIP

As discussed in last week’s Interim Update, meaningful declines in the T-Bond price over the past few decades generally have been driven by rising inflation expectations and/or the Fed’s rate-hiking. They generally have NOT been driven by accelerating supply growth or concerns about the same. The main reason is that in the past the T-Bond supply tended to ramp up in parallel with economic and financial market conditions that prompted a substantial increase in the desire to hold T-Bonds, so much so that the increase in demand for the perceived safety provided by Treasury debt trumped the increase in the supply of this debt.

The recent past has been different, in that the decline in the T-Bond price over the past four months and especially over the past month was not driven by changing expectations regarding inflation or the Fed’s monetary tightening. We know that this is the case because the “inflation” rates factored into the TIPS market (what we sometimes refer to as the “expected CPI”) have been stable, as were the prices of the most relevant Fed Funds Futures contracts prior to the past few days. Instead, the main driver was concerns about the pace at which the supply of government debt will grow over the coming year due to current spending plans, rapidly rising interest expense, and a likely large increase in government deficit-spending after the economy slides into recession. This difference matters to the gold market.

The recent increase in the ‘real’ yield on Treasury bonds has not been as bearish for gold as it normally would be, because the concerns about the US fiscal situation that have been driving the T-Bond price downward and the real T-Bond yield upward also have been boosting the investment demand for gold. We suspect that this is not so much due to the rapid increase in the government’s indebtedness in and of itself, but due to the eventual economic and monetary consequences of the burgeoning government debt.

The eventual economic consequences include slower growth as more resources get used and allocated by the government. A likely monetary consequence is that regardless of what senior members of the Fed currently say and think (they naturally will insist that the Fed is independent), there’s a high probability that the Fed eventually will be called upon to help finance the government.

Print This Post

Print This Post