Here is an excerpt from a recent TSI commentary about another absurd course of action now being seriously considered by the monetary maestros.

Once upon a time, the concept of “helicopter money” was something of a joke. It was part of a parable written by Milton Friedman to make a point about how a community would react to a sudden, one-off increase in the money supply. Now, however, “helicopter money” has become a serious policy consideration. So, what exactly is it, how would it affect the economy and what are its chances of actually being implemented?

“Helicopter money” is really just Quantitative Easing (QE) by another name. QE hasn’t done what central bankers expected it to do, so the idea that is now taking root is to do more of it but call it something else. Apparently, calling it something else might help it to work (yes, the people at the upper echelons of central banks really are that stupid). The alternative would be to question the models and theories upon which QE is based, but such questioning of underlying principles must never be done under any circumstances. A Keynesian economist calling into question the principle that an economy can be made stronger via methods that artificially stimulate “aggregate demand” would be akin to the Pope questioning the existence of god.

The only difference between QE as practiced by the Fed and “helicopter money” is the path via which the new money gets injected. Under the Fed’s previous QE programs, new money was created via the monetisation of debt and ended up in the accounts of securities dealers*. Under a “helicopter money” program, new money would still be created via the monetisation of debt. However, in this case the new money would be placed by the government into the accounts of the general public, via, for example, tax cuts and welfare payments (handouts), and/or placed by the government into the accounts of contractors working for the government.

If promoted in the right way, “helicopter money” could have widespread appeal among the general public. Unlike the Fed’s traditional QE, which had the superficial effect of making the infamous top-1% richer and the majority of the population poorer, the average member of the voting public could perceive an advantage for himself/herself in “helicopter money”. Unfortunately, regardless of who gets the new money first there is no way that an economy can be anything other than weakened by the creation of money out of nothing. The reason is that the new money falsifies the price signals upon which economic decisions are made, leading to ill-conceived investments and other spending errors.

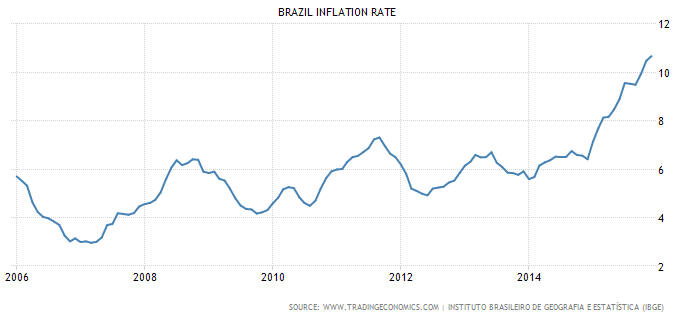

Due to the distortions of price signals that they bring about, both traditional QE and “helicopter money” are bad for the economy. However, an argument could be made that “helicopter money” is the lesser of the two evils. The reason is that with “helicopter money” the effects of the monetary inflation will more quickly become apparent in everyday expenses and the popular price indices. That is, “helicopter money” will quickly lead to inflationary effects that are obvious to everyone. This limits the extent to which the policy can be implemented.

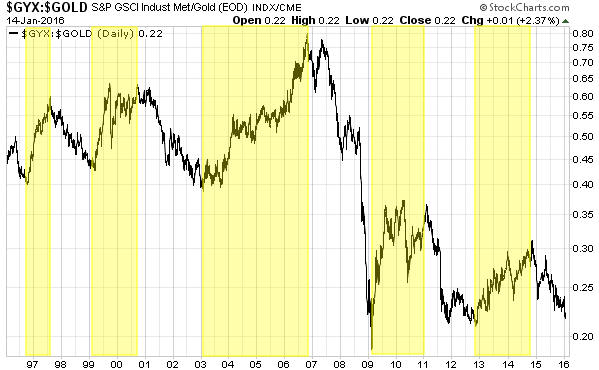

Putting it another way, traditional QE had by far its biggest effects on the prices of things that, according to the average economist, central banker and politician, don’t count when assessing “inflation”, whereas the effects of “helicopter money” would soon become obvious in the prices of things that do count. A consequence is that a “helicopter money” program would be reined-in relatively quickly and the long-term damage to the economy would be mitigated.

With regard to the chances of “helicopter money” actually being implemented, we think the chances are very good in Japan, very poor in the euro-zone (due to there being a single central bank ‘serving’ a politically-disparate group of countries) and somewhere in between in the US.

Although it presently seems like the more extreme policy, the US has a better chance of experiencing “helicopter money” than negative interest rates within the next two years. This is because a) the next US president will be an economically-illiterate populist (regardless of who wins in November), b) the average voter will likely perceive a financial advantage from “helicopter money”, and c) hardly anyone outside the halls of Keynesian academia will perceive anything other than a disadvantage from the imposition of negative interest rates.

In summary, then, “helicopter money” is QE by a different name and path. It would inevitably reduce the rate of economic progress, but it has a reasonable chance of being implemented in the US the next time that policy-makers are desperate to do something.

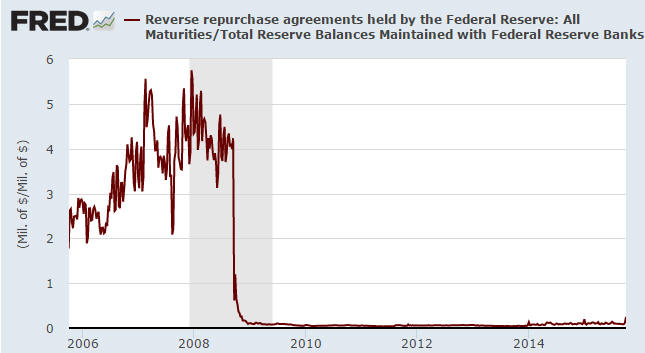

*Every dollar of Fed QE adds one dollar to the commercial bank account of a Primary Dealer (PD) and one dollar to the reserve account at the Fed of the PD’s bank, meaning that every dollar of QE adds one reserve-covered dollar to the economy-wide money supply.

Print This Post

Print This Post