I update gold’s true fundamentals* every week in commentaries and charts at the TSI web site, but my most recent blog post on the topic was on 20th March. At that time the fundamental backdrop was gold-bearish. What’s the current situation?

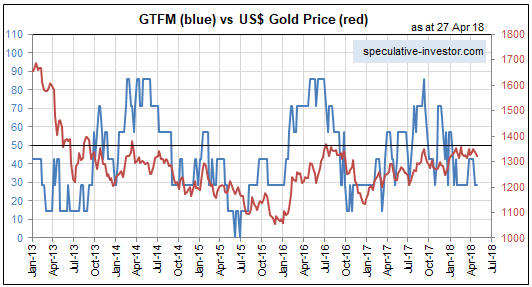

The fundamental backdrop (from gold’s perspective) is little changed since 20th March. In fact, it has not changed much since early this year. My Gold True Fundamentals Model (GTFM), a weekly chart of which is displayed below, turned bearish during the first half of January and was still bearish at the end of last week. There have been fluctuations along the way, but at no time over the past 3.5 months has the fundamental backdrop been supportive of the gold price.

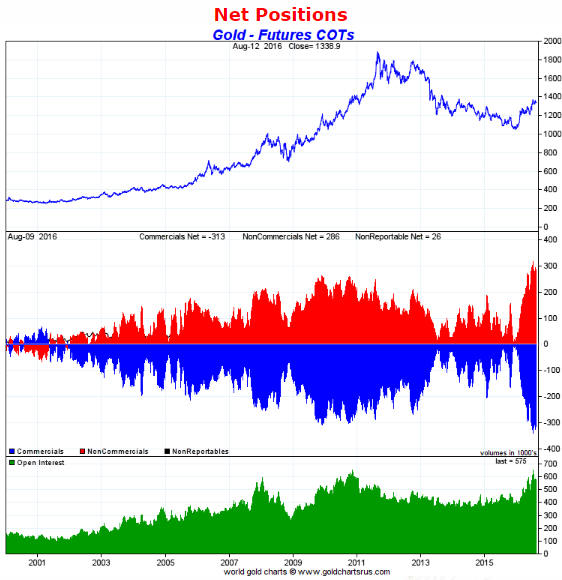

It’s possible for a tradable rally in the US$ gold price to get underway at a time when the fundamental backdrop is not gold-bullish, but for this to happen the sentiment situation as indicated by the Commitments of Traders data would have to be very supportive or the US$ would have to be very weak. Currently, the fundamental backdrop is bearish, the sentiment situation is neutral and the Dollar Index has just broken out to the upside. Therefore, as things stand today there is no good reason to expect that a substantial gold rally will get underway in the near future.

Based on how I expect the fundamentals to shift over the weeks ahead my guess is that a substantial gold rally will begin from a May-June low. However, there is more to be lost than gained by ‘jumping the gun’ and buying a short-term trading position now in anticipation of such a rally.

*Note that I use the word “true” to distinguish the actual fundamental drivers of the gold price from the drivers that are regularly cited by gold-market analysts and commentators. According to many pontificators on the gold market, gold’s fundamentals include the volume of metal flowing into the inventories of gold ETFs, China’s gold imports, the volume of gold being transferred out of the Shanghai Futures Exchange inventory, the amount of “registered” gold at the COMEX, India’s monsoon and wedding seasons, jewellery demand, the amount of gold being bought/sold by various central banks, changes in mine production and scrap supply, and wild guesses regarding JP Morgan’s exposure to gold. These aren’t true fundamental price drivers. At best, they are distractions.

Print This Post

Print This Post