A popular line of thinking is that the US banking system is not making as much use of its “excess” reserves as it should be because of the interest rate that the Fed now pays on these reserves. This line of thinking reflects a basic misunderstanding of how the banking system works.

There are two reasons why it is wrong to believe that the 0.50% interest rate now being earned by US banks on their reserves is encouraging the banks to stockpile money at the Fed rather than take a risk by making more loans. The first reason is that there is no relationship between bank lending (and the associated creation of new bank deposits) and bank reserves. I’ve covered this concept in previous blog posts, including HERE, so today I’ll focus on the second reason.

The second reason is that the banking system has no control over its reserves. An individual bank can reduce its reserves by lending reserves to another bank, but banks as a group have no say in the total quantity of reserves. In other words, even if the US banking system desperately wanted to reduce its collective reserve quantity it would be powerless to do so.

By way of further explanation, there are only three ways that reserves can leave the US banking system. They can be removed by the Fed (the Fed has unlimited power to add or delete reserves), they can exit in the form of notes and coins in response to increasing public demand for physical cash, or they can be transferred to governmental accounts at the Fed. The third way will always be temporary because the government is always quick to spend any money it gets, so there are really just two ways that the banking system’s reserves can decline: a deliberate action by the Fed or increased demand for physical cash within the economy.

In other words, regardless of how many loans are made and how many new commercial bank deposits are created, every dollar of reserves currently in the US banking system will remain there until the Fed decides to change the system-wide level or until it leaks into the economy via the conversion of electronic deposits to physical cash.

An implication is that changing the rate of interest that the Fed pays on reserves will not affect the pace at which banks expand/contract credit within the economy. For example, if the Fed increased the interest rate on reserves from 0.50% to 1.00% the banks would generate more interest income from their reserves, but there would be no change in the incentive to make new loans because the banks will earn this additional income regardless of whether they lend more or less money into the economy (the creation of a bank loan doesn’t cause bank reserves to disappear). For another example, if instead of paying banks a positive rate on their reserves the Fed started charging banks, that is, if the Fed adopted Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP), the banking system as a whole would have no additional incentive to grow its loan book since there would be nothing it could do to avoid the cost. In fact, the cost imposed by the NIRP could indirectly REDUCE the incentive to make new loans.

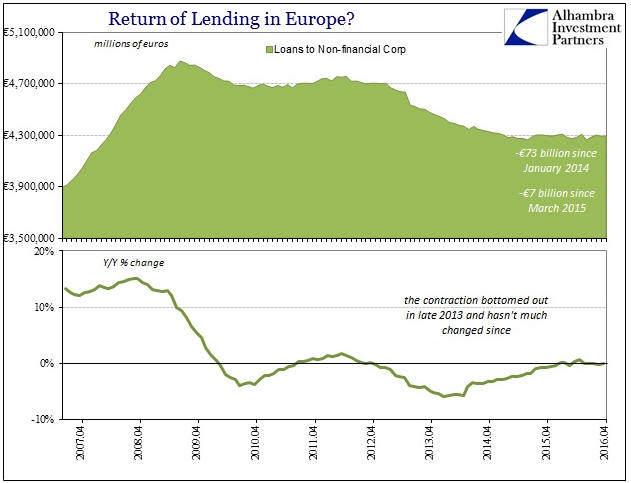

As an aside, this doesn’t guarantee that NIRP won’t happen in the US, especially given the evidence that the Fed’s senior management is almost as clueless as Mario Draghi. However, the obvious failure of the policy in Europe lessens the risk of it happening in the US.

Summing up, the interest rate paid on reserves cannot be a reason for either more or less bank lending. As explained previously, the only reason that the Fed began paying interest on bank reserves in late-2008 was to enable it to maintain control of the Fed Funds Rate while it pumped huge volumes of dollars into the economy and into the reserve accounts of banks.

Print This Post

Print This Post