The price of gold is dominated by investment demand* to such an extent that nothing else matters as far as its price performance is concerned. Investment demand is also the most important driver of silver’s price trend, although in silver’s case industrial demand is also a factor to be reckoned with. In addition, changes in mine supply have some effect on the silver market, because unlike the situation in the gold market the annual supply of newly-mined silver is not trivial relative to the existing aboveground supply of the metal.

Given that the change in annual mine supply is irrelevant to the gold price and is not close to being the most important driver of the silver price, why do some analysts argue that the gold/silver ratio should reflect the relative rarities of the two metals in the ground and therefore be 10:1 or lower? I don’t know, but it isn’t a valid argument.

A second way of using relative rarity to come up with a very low gold/silver ratio is to assert that the price ratio should be based on the comparative amounts of aboveground supply. Depending on how the aboveground supplies are calculated, this method could lead to the conclusion that silver should be more expensive than gold. It would also lead to the conclusion that gold should be the cheapest of all the world’s commonly-traded metals, instead of the most expensive. For example, if gold’s relatively-large aboveground supply was a reason for a relatively low gold price then gold should not only be cheaper than silver, but also cheaper than copper.

Another argument is that the gold/silver ratio should be around 16:1 because that’s what it averaged for hundreds of years prior to the last hundred years. This is also not a valid argument, because changes in technology and the monetary system can cause permanent changes to occur in the relative values of different commodities and different investments. For example, when monetary inflation was constrained by the Gold Standard the stock market’s average dividend yield was always higher than the average yield on the longest-dated bonds, but the 1934-1971 phasing-out of the official link to gold permanently altered this relationship. In a world where commercial and central banks can inflate at will, the stock market will always yield less than the bond market (except when the central-bank leadership goes completely ‘off its rocker’ and implements the manipulation known as NIRP). This is because stocks have some built-in protection against inflation. The point is that the ratio of gold and silver prices during an historical period in which both metals were officially “money” does not tell us what the ratio should be now that neither metal is officially money and one of the markets (silver) has a significant industrial demand component.

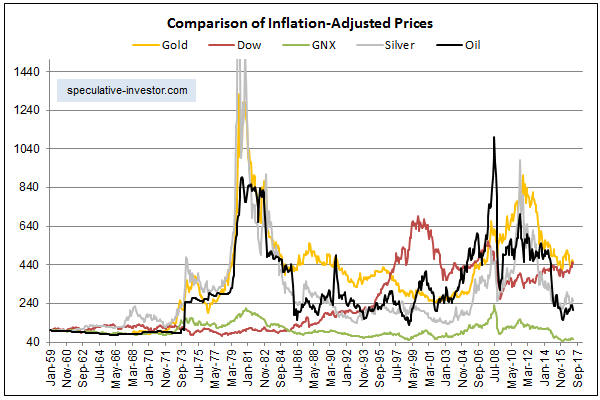

The global monetary system’s current configuration dates back to the early 1970s, when the last remaining official link between gold and the US$ was severed. This probably means that we can look at how gold and silver have performed relative to each other since the early 1970s to determine what’s normal and what’s possible. With reference to the following chart, here’s a summary of what happened during this period:

a) The gold/silver ratio spent the bulk of the 1970s in the 30-40 range, but broke out of this range to the downside during the second half of 1979 in response to massive accumulation of silver bullion and silver futures by the Hunt brothers.

b) The ratio dropped as low as 16:1 in January of 1980, but then returned to 40 in the ‘blink of an eye’ as rule changes by the commodity exchange created financial problems for the highly-geared Hunts and a commodity-investment bubble began to deflate.

c) During the second half of the 1980s the ratio trended upward as US financial corporations weakened. The ratio peaked at around 100 at the beginning of 1990s in parallel with a full-blown banking crisis that almost resulted in the collapse of some of the largest US banks.

d) The ratio trended lower throughout the 1990s as the banks recovered (with the help of the Fed) and financial assets trended upward.

e) From the late 1990s through to the beginning of 2011 the ratio oscillated between 45 and 80, with 80 being reached near the peaks of financial crises (early-2003 and late-2008) and 45 being reached in response to generally high levels of economic confidence.

f) In February of 2011 the ratio broke below the bottom of its long-term range and rapidly moved down to around 30. The huge price run-up in silver that led to this large/fast decline in the gold/silver ratio was fueled by the overt bullishness of a high-profile/well-heeled speculator (Eric Sprott) and by various rumours, including rumours of silver shortages and the unwinding of a price-suppression scheme led by JP Morgan. There were no silver shortages and there was no price-suppression scheme to be unwound, but as is often the case in the financial markets the facts didn’t get in the way of a good story.

g) The 2010-2011 parabolic rise in the silver price ended the same way that every similar episode in world history ended — with a price collapse.

h) Silver’s Q2-2011 price collapse set in motion a major, multi-year upward trend in the gold/silver ratio. In this case, the upward trend in the ratio was driven by the deflating of a commodity investment bubble and problems in the European banking industry. The ratio rose all the way to the low-80s and is still at an unusually-high level in the 70s.

The gold/silver ratio’s performance over the past five decades suggests that the 45-60 range can now be considered normal, with moves well beyond the top of this range requiring a banking crisis and/or bursting bubble and moves well beyond the bottom of this range requiring rampant speculation focused on silver.

*In this post I’m lumping speculative, safe-haven and savings-related demand together under the term “investment demand”.

Print This Post

Print This Post