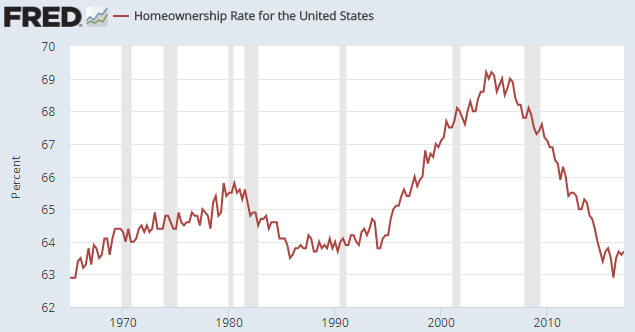

In a 2015 blog post titled “Unintended Consequences” I explained that policies implemented by the Clinton and Bush administrations to boost the rate of home ownership not only had unintended consequences, but the opposite of the intended consequence. This post is a brief update on the US home ownership situation.

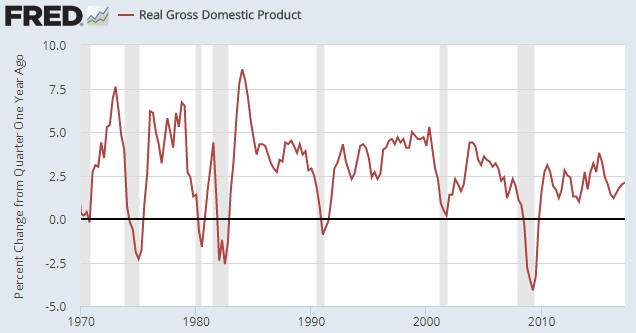

As evidenced by the following chart, the government was initially successful in its endeavours. The home-ownership rate sky-rocketed during the second half of the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s as it became possible for almost anyone to borrow money to buy a house. As also evidenced by the following chart, the home-ownership rate subsequently collapsed. The collapse was an inevitable consequence of people throughout the economy first responding to the Fed’s and the government’s incentives to take on excessive debt and then finding themselves in drastically-weakened financial situations.

The home ownership rate ended up bottoming in Q2-2016 at a 50-year low.

No one in the government or at the Fed has ever admitted culpability for the mortgage-related debt binge that led to the spectacular rise and equally-spectacular fall in the US home-ownership rate. Apparently, it was a market failure.

Print This Post

Print This Post