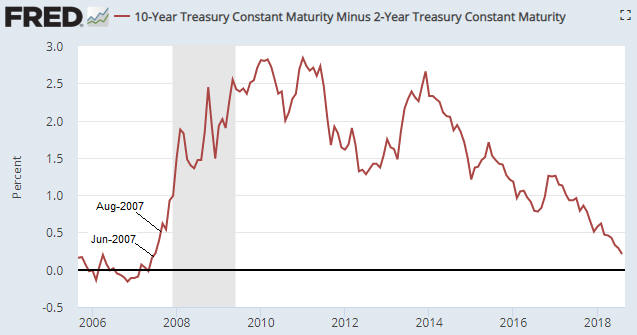

There is an age-old relationship between prices and interest rates that Keynesian economists have called a paradox (“Gibson’s Paradox”). The relationship was clearer during the Gold Standard era, but as I explained in a previous post it is still apparent if prices are measured in gold.

To understand “Gibson’s Paradox” and why it actually isn’t a paradox, refer to the earlier post linked above. Suffice to say that when money is sound or at least a lot sounder than it is today, interest rates don’t drive prices and prices don’t drive interest rates; instead, on an economy-wide basis both prices (in general) and risk-free interest rates are driven by changes in societal time preference. Moreover, as mentioned above and explained in my earlier post, even with today’s massive, continuous manipulation of interest rates by central banks the relationship is still evident, but only when interest rates are compared to a wholesale price index denominated in gold.

The commodity/gold ratio is the price of a broad-based basket of commodities in gold terms. In essence, it is a wholesale price index using gold as the monetary measuring stick. Also, the risk-free US interest rate that is least affected by the direct manipulation of the Fed is the yield on the 30-year T-Bond, so if the age-old relationship still works then what we should see is a positive correlation between the commodity/gold ratio and the T-Bond yield. Or, looking at it from a different angle, what we should see is a positive correlation between the gold/commodity ratio and the T-Bond price. That’s exactly what we do see.

Using the Goldman Sachs Spot Commodity Index (GNX) to represent commodities, the following chart shows that the age-old relationship has worked over the past 12 years when gold is the monetary measuring stick.

The next chart zooms in on the most recent 2 years and shows that over the past three weeks there has been a significant divergence, with the gold/commodity ratio turning upward and the T-Bond price staying on a downward path. It’s a good bet that this divergence will be eliminated within the next two months via either a decline in the gold/commodity ratio to a new multi-year low or a rebound in the T-Bond. My money is on the latter.

Print This Post

Print This Post